Maria Theresa Phipoe had fallen on hard times but was making the best of it. Now, in 1797, she lodged in Garden Street with Letitia Munday, in the parish of St George’s in the East, more than a step down from her previous abode in the salubrious suburb of Chelsea. Her once-thriving business procuring young women was over; these days she dealt only in stolen hardware: china, clothes, tablecloths, linens. To go with her new life she had a new name: she was known to her neighbours as Mary Benson, a supposed French emigrée who boasted of a portfolio of property (inconveniently tied up in litigation).

St George’s in the East stands just off The Highway in Wapping. © Copyright David Williams and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

One of her regular customers for stolen items was Mary Cox. Generally they got on well, although Cox could be sharp-tempered at times, as indeed could Phipoe.

On 25 October 1797 Cox called at Garden Street and went upstairs to Phipoe’s room. A short time later Phipoe sent her landlady Mrs Munday out for a threepenny loaf and a pint of brandy. When she returned, Phipoe told her that she was not ready to receive her, and that she would call down when she was. After a while, Mrs Munday began hearing some really quite alarming sounds from Phipoe’s room, so she enlisted her niece Elizabeth Eyles and Margaret MacDonald, a neighbour, come with her to investigate.

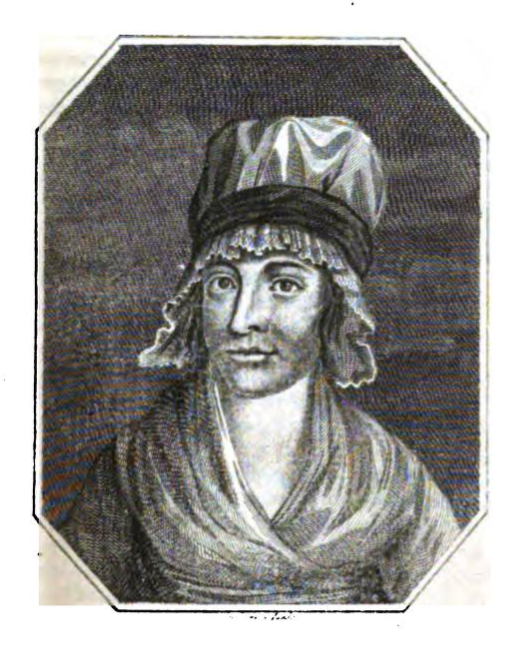

Maria Theresa Phipoe (The criminal recorder; or, Biographical sketches of notorious public characters)

‘What is the matter?’ she called through the door of Phipoe’s room, the other two women behind her.

‘Nothing at all,’ came Phipoe’s answer. ‘Mrs Cox has had a pain in her stomach and had a fit.’

‘I’ll go for the doctor,’ replied Mrs Munday.

‘No need, Mrs Munday. Mrs Cox is already feeling better. Have you got anyone else out there with you?’

‘Yes, I’m with my cousin Miss Eyles and Mrs MacDonald.’

During the conversation the women could hear groaning from inside Mrs Phipoe’s room.

‘It sounds like someone dying,’ said Miss Eyles.

After a few minutes Phipoe opened the door a fraction.

‘You may come in, Mrs Munday. No other person has any business here,’ she said, but Mrs Munday hesitated.

‘I’ll not come in alone,’ she said, and turned around, whispering to the others that she would go for a surgeon, and a beadle. She took Elizabeth Eyles with her.

Mrs MacDonald pushed the door open and what she saw in the room was ghastly. Phipoe was holding a severed finger in a bloody handkerchief, and there on bedding on the floor was Mary Cox, one hand supporting her head and the other holding her apron to a gaping wound in her neck. She was ‘bleeding like an ox,’ to quote words Mrs MacDonald used later in court.

‘Good God. Has the Lord left you? What have you been about, Mrs Benson [if you remember, this was the name Phipoe went by], that your passion has overruled your reason?’

‘My dear Mrs MacDonald,’ she replied, ‘look at my finger. See what she has done.’

The house became a chaotic scene: Mary Cox had struggled downstairs and wanted to leave the house to get away from her attacker; Mrs Munday had returned, and was followed soon after by a surgeon and two beadles of the parish; Mrs Benson roaming around; blood everywhere. The surgeon did his best to dress Cox’s wounds – she had also been stabbed several times in the breast – while the beadles asked her questions. But she could barely speak, only indicating yes and no with gestures. At last she was taken to London Hospital, half a mile away.

Beadle, St Martin in the Fields, London

At one point, Grey, one of the beadles, found Phipoe upstairs sitting on the bed.

‘God Almighty! What have you been about?’ he asked.

‘I believe the Devil and passion have bewitched me,’ she said.

He spotted a knife and the severed finger.

‘Is that your finger?’ he asked.

‘Yes, that woman downstairs, Mrs Cox, cut it off.’

Because she also needed treatment, he took her to the London Hospital, where a nurse found a knife hidden in her stays. The surgeon looked at her hand and saw that the finger bone was cut cleanly across – not an injury typically sustained during a fight.

A magistrate came to the hospital to take a deposition from Mary Cox, something he was questioned about later at Phipoe’s trial. How could she give a statement? She could not speak. He swore that the account had come from her own mouth.

Mary Cox died the next day.

At her trial, after the witnesses against her had given evidence and Mary Cox’s deposition was read out, Maria Phipoe addressed the court. She had quarrelled with Cox when trying to strike a deal, she said. Phipoe owed rent and wished to sell her watch and earrings, but not for the paltry sum Cox was offering. Cox had insulted her, saying, ‘I suppose you want to go to London to be Mr. Courtoys’ whore again.’

It seems Cox knew all about Phipoe’s past. She had touched a nerve.

Two years previously, Phipoe had been prosecuted by John Courtoys (or Curtois), a peruke-maker of great fortune. One evening in April 1795, in expectation of Courtoys’ visit to her home in Hans Place, near Sloane Street, Phipoe made careful preparations. He owed her money, she said later. He was certainly on his guard when he arrived, and was reluctant to be alone with Phipoe. He was eventually persuaded to go upstairs but he was right to be suspicious – as soon as he was in the room Phipoe and her maid Mary Brown pinned him to an armchair and tied him in. Phipoe picked up a carving knife and in the struggle Courtoys sustained a deep cut to his hand. To further concentrate his mind she had artfully placed on the table two pistols, with gunpowder and shot in a wineglass.

Phipoe proceeded to berate and threaten her prisoner, and when she had achieved the correct degree of compliance, forced him to write her a promissory note for £2000. Meanwhile, downstairs in the back parlour sat ‘Mr Caddle’, to whom Mary Brown carried drafts of the note ‘for mending’, as the maid later put it. After Phipoe had succeeded in getting the note as she wanted it, she coolly instructed Mary Brown to bring up a bottle of sherry and offered Courtoys a drink. He refused and fled the house as soon as he could. Phipoe gave chase, armed with the pistols.

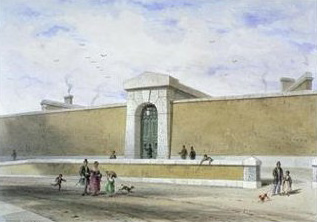

Tothill Fields Bridewell

Courtoys went straight for help and soon some Bow Street officers arrived to arrest Phipoe and her maid. They were committed to separate prisons (Phipoe to Tothill Fields, Mary to Newgate). Phipoe sent Mary a guinea for her maintenance. On 20 May Mary appeared as a prosecution witness at the Old Bailey, where Phipoe faced the capital charge of violent theft. Although she was represented by counsel (William Fielding) she had no specific defence and it can have surprised no one that after the six-hour trial was over she was found guilty. She escaped death, however, because a fault in the indictment immediately became apparent. It was noted that it read ‘that this offence was against the statute’ whereas it should have read ‘statutes’. That was not the only problem with the charge; in February 1796 it was determined that Phipoe could not be guilty of theft because the promissory note had not been stolen from Courtoys (indeed it was written on Phipoe’s own paper with her own ink) and, in his own possession, had no value. An alternative charge was made, but the prosecutor offered no evidence and the case was dismissed.

Phipoe was punished by losing her home and her gentleman customers, and was forced to decamp to Wapping and a new life as a fence. The Sporting Magazine reported that after the collapse of the Courtoys case, she was imprisoned for a year for receiving stolen goods, and she certainly was in Newgate for a while.1

Maria Theresa Phipoe was a Roman Catholic, born in Dublin and lived for many years in France. In appearance, she was, in the words of The Sporting Magazine, ‘thick-set’ and ‘apparently very strong’. The notes against her entry in the Criminal Register2 record her as 5 feet tall, with a sallow complexion, brown hair and grey eyes.

The Old Bailey (1814), from Ackermann’s Repository of the Arts

At her Old Bailey trial for murdering Mary Cox, Mr Justice Perryn noted that she had given more than one version of events; that she had denied entry to the room to the women who had come to investigate; and that she showed no sign of insanity. The jury took only 20 minutes to return their guilty verdict and a sentence of death automatically followed. A search of her person when she was removed from court yielded a large bottle of laudanum. Possibly she had meant to use it to destroy herself.

Before her execution on 11 December 1797 she was reported to have to have wept and shown penitence. She confessed that her finger had been cut in the scuffle with Mary Cox but denied deliberately cutting it off herself. She attributed her crimes to the use of laudanum. On the day of her death, she appeared strong, ‘her countenance not changing till the cap was drawing over her face’.3 She left a guinea for the most deserving debtor in Newgate and gave the same to her executioner. Her body was exhibited to the public in a court near to the site of the gallows.4

Maria Phipoe is one of 131 women who were hanged in England and Wales featured in my book Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches.

- 1798, Vol 11

- HO 26 and HO 27, and HO CR NAHOCR700020117

- Hampshire Chronicle, 16 December 1797

- It is not known exactly where the gallows was sited during this period.

Leave a Reply