“’Tis to let the Ghost of Gold

“’Tis to let the Ghost of Gold

Take from Toil a thousandfold

More than e’er its substance could

In the tyrannies of old.

“Paper Coin—that forgery

Of the title-deeds which ye

Hold to something of the worth

Of the inheritance of the Earth.” – Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘The Mask of Anarchy’, 1819

As far as we know, Sarah Bailey was born, or at least lived in, Newport on the Isle of Wight. She was married to James Bailey, “a mariner”, and earned money as a hawker. She was probably in her 20s. In 1799, during her travels around the country, and with the help of an unnamed accomplice, she passed off a number of low-value counterfeit Bank of England notes. This was the time of the Restriction, when the country was flooded with badly designed one pound and two pound Bank of England notes. It was easy to copy them and for many the temptation was too great to resist.

The Restriction had been imposed to meet the threat of economic implosion. On request, banks were obliged to “pay the bearer” of a banknote issued by that bank the appropriate value in gold (that is, gold and silver coins). These were so-called specie payments.1 In 1795, gold bullion stocks at the Bank of England were running low, the result of the drain caused by the war with France and a series of bad harvests. The Bank reacted by reducing the number of banknotes in circulation but this policy failed after a series of runs on banks in the north east (Newcastle, Sunderland and Durham). Panicked, the public started hoarding coins, which in turn led to a shortage of metal currency.

Provincial banks suspended specie payments, spreading more alarm. This increased the demand for Bank of England notes, before its specie payments ended in 1797. The financial structure of the country was now teetering. Prime Minister William Pitt stepped in, and in a well-judged move, announced that the suspension was merely temporary; bankers and merchants supported his line and endorsed Bank of England notes for all transactions and on 3 May the Bank Restriction Act was passed. The Bank was allowed to issue small denomination notes, which it did in copious quantities.

The effect was to encourage the forgery of Bank of England notes on a massive scale. The relatively simple design of the notes, which had been cheaply and hastily printed, was easy to imitate. The victims of the frauds were generally from the poorer sections of society – publicans, small retailers, market stall owners – many of them functionally illiterate, who found it difficult to detect forgeries. Indeed, some of the forgeries were so accurate that the Bank of England’s own inspectors could not distinguish them.

Given the numbers of people involved in forgery and distribution and their subsequent judicial deaths or transportations, it is tragic that a process for producing counterfeit-proof notes was not adopted by the Bank. This would have put many criminals out of business immediately. In 1790, newspaper publisher Alexander Tilloch offered the Bank of England his stereotype method for producing notes that would be impossible to counterfeit. He tried again in 1797 but they again rejected it.2 The penalties for uttering, or even possession, were severe: hanging at worst or transportation for life, although in 1801 the lesser charge of possession was introduced, punished by 14 years transportation. The Bank, as did the decision-makers generally, preferred to deter crime by punishing it severely, but they were in a particular, and strange, moral position: they were protecting the currency but their policies, of making large numbers of low denomination notes available and not designing them securely, were responsible for the high incidence of the crime. Add to that, there was a growing feeling that not all crime was the result of ‘sin’ and that life circumstances (poverty) had a lot to do with it. As time went on, and the numbers going to the gallows increased, this produced a backlash of criticism and revulsion at the way the Bank put commercial considerations over human life.

During this period, the Bank was developing its own system for detection and prosecution, both almost entirely separate from the normal processes of the judiciary. With its vast resources of investigating officers and solicitors, the Bank was a powerful adversary. Generally, the Bank only pursued those cases where the case was robust but that did not mean they were “let off”. It is likely that many forgers and utterers were not prosecuted, or even apprehended, at the time they were detected. Some were spied on, and arrested only when the Bank had accumulated better evidence against them; some were persuaded to provide information against others in return for mitigation. Many were caught in elaborate entrapments, providing more grounds for criticism.

The centre of manufacture of bad banknotes was not London, where large numbers of them were passed, but the north, particularly Birmingham and Liverpool, but also, in 1799 it seems, in Leeds. It was a cluster of bad notes in the market town of Otley, near Leeds in Yorkshire, that attracted the attention of the Bank of England, which sent Mr Bliss, accompanied by Thomas Carpmeal, a Bow Street officer, to Leeds to investigate.

An overview of Otley, West Yorkshire (2006). Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

While the forgers themselves were usually male, many of those who uttered the notes were female. They exchanged one pound and two pound notes for low-value goods in inns and shops in the high street or at fairs and markets where they attracted less attention than men and were simply more plausible. Sarah, who was now in Otley, operated mainly at markets, where she would exchange her counterfeit notes for small trifles. She was skilled and strategic. One of her ploys was to deliberately drop a set of keys amongst crockery, breaking it. Of course she politely paid up, generously gave broken pieces away to others, took the change for her note and “marched off with the spoil”. The shopkeeper was the victim of a classic distraction crime.

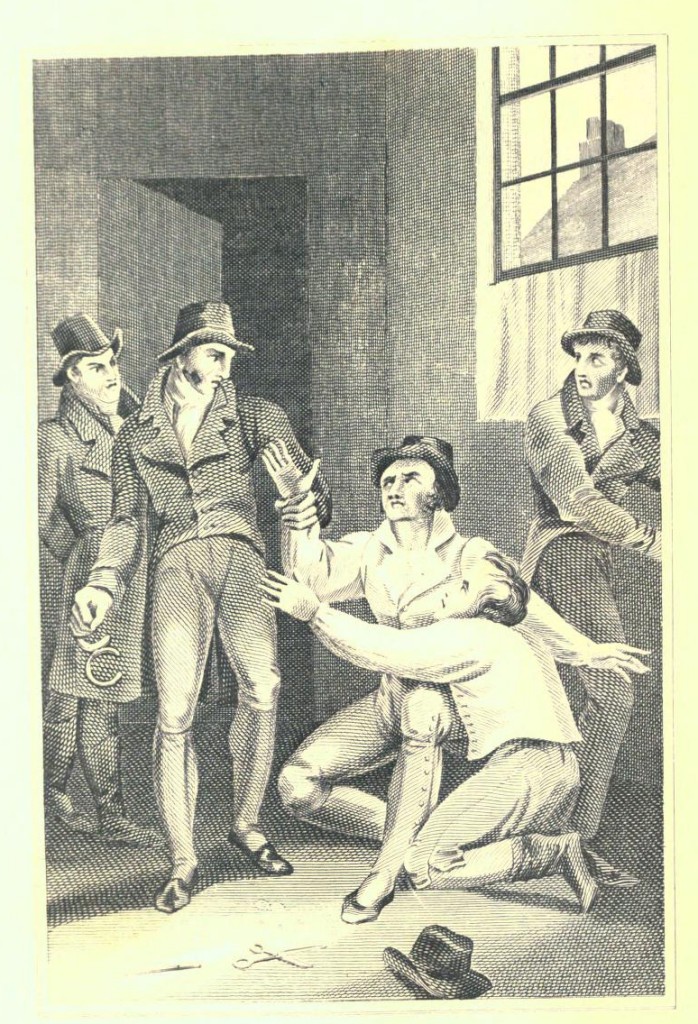

Bow Street Runners arrest Thomas Brock, Thomas Pelham and Michael Power for currency offences (1816). From George Wilkinson, The Newgate calendar improved; being interesting memoirs of notorious characters who have been convicted of offences against the laws.

Bliss and Carpmeal arrived in Otley on 26 October 1799 and discovered that about a fortnight earlier Sarah, who had many other names including the rather wonderful “Betty Blitchin'” was in custody for passing off a counterfeit one pound note on Catherine Pybus, whose husband Thomas was an innkeeper at Otley. She was also charged with stealing a silver mug from “the landlord” and concealing it in the curtains of her bed, from which we might assume that she was a guest staying at the inn. “The landlord” (presumably Thomas Pybus) arrested her himself and called in two constables to take her to the local Justice of the Peace.

Sarah was a quick thinker. After her examination by Thomas Clifton, she managed to evade the constables and get a place on the mail coach to Sheffield. Unfortunately for her, they caught up with her only 15 minutes before it was due to depart. However, she then managed to purloin the silver mug and get rid of it.

The Constable, who had charge of the mug… was perfectly astounded when it was not to be found. He looked about, and began to consider whether there was not magic in the business. He searched in the crown of his hat, he even examined his inexpressibles3; but was at last relieved from his embarrassment by a Gentleman, who found the cup upon the road.4

That night, Sarah was placed in the care of the Otley Volunteers, and to ensure that she did not escape her guards were locked up with her. We can assume that she was back with the Pybuses at the inn because “the landlord” had charge of the key. That night, Sarah sang Wesleyan hymns, prayed fervently, protested her innocence, and managed to persuade one of the Volunteers to help her escape. While the others slept, using sheets and blankets tied together with her garters, she lowered herself (“although a very lusty woman”) from the first floor window5 into the street.

Charles Ansell, Guard-Room Tactics; Bugs in Danger; or a Volunteer Corps in Action (1798). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

A passer-by noticed the blankets and alerted the officer in charge, who immediately assembled his men and ordered drums to be beat. In the end, Sarah found hiding out in a hayloft about three miles away.

The Bank and judicial authorities, steeped in the values of respectability and gentility, would have viewed Sarah’s outrageous and unfeminine behaviour – her multiple crimes, flagrant attempt to destroy evidence, manipulation of the hapless Otley Volunteers, and repeated attempts to escape – with horror. Their retribution was bound to be severe, and Sarah had no real chance of the lesser punishment of transportation.

The next we hear about Sarah is that she has been hanged at York Castle alongside John M’William, a forger. In the clichéd words of the newspaper reports, she “appeared … to have a strict sense of [her] unfortunate situation, and conducted [herself] in [her] last moments, with becoming fortitude”. As this formulaic sentence was used in almost every report of executions, it is unlikely to be accurate. There is no hint of Sarah’s nose-thumbing verve.

George Cruikshank, Bank Restriction Note (1819)

Forgery of banknotes was made a capital crime in 1697 and in 1725 extended to offering, disposing or putting away a forged note. Ironically, between 1802 and 1832, the Bank offered plea bargains to many; essentially, if they agreed to plead guilty to possession the Bank would not press capital charges. If the accused insisted on their innocence and were found guilty, however, the Bank was implacable. In 1818, Harriet Skelton, whose cause was taken up by Elizabeth Fry and others, found this to her cost.

The number of executions and the way in which the Bank used entrapment techniques gave rise to disquiet amongst the middle-classes. The Leeds Intelligencer‘s report of Sarah’s escapades was careful to give the Bank’s justification for sending investigators to Otley:

It had been discovered that a great number of forged Bank of England Notes had been circulated near Leeds, and particularly at Otley, in Yorkshire, as well as all the adjoining neighbourhood; and it becoming therefore necessary to institute a diligent enquiry, which might lead to a detection, the Governors and Directors of the Bank very properly sent those persons into that part of the country.

Leigh Hunt, perhaps referencing Henry Fielding’s famous An Enquiry into the Late Increase in Crime, bewailed “the late great increase in the number of forged Bank Notes,” pointing out that retailers, who had no resource to compensation when they were defrauded, suffered major losses without recompense (because the Bank was the victim rather than the shopkeeper). The genuine notes were “clumsy, ill-invented and worse executed”. Hanging without mercy and transportation was doing nothing to deter forgers and utterers (“numberless unhappy wretches”), and he urged that another solution be found. He despaired of the Bank’s policies. “The Bank is rich and flourishing,” he wrote. “Riches, we all know, harden the heart.”

In 1821 the Bank Restriction period ended and a tidal wave of executions began to recede. In 1832 the Punishment of Death Act abolished the death penalty for theft, counterfeiting, and forgery67

- British banknotes still include the words “I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of…”

- In 1810 the Bank brought in Augustus Applegath’s process, which Tilloch claimed was remarkably similar to his own.

- Underwear

- Leeds Intelligencer, 4 November 1799.

- In the US, second floor

- Except for the forgery of wills and certain powers of attorney.

- I am indebted to Deirdre E. Palk’s Gender, Crime and Discretion in the English Criminal Justice System, 17802 to 1830s (2001) and to the following paper: Crosby, Mark. “The Bank Restriction Act (1797) and Banknote Forgery.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. Accessed 2016-04-10.

Leave a Reply