- Publisher: Pen & Sword

- Available in: Hardback

- ISBN: 1473863341

- Published: 30 November 2017

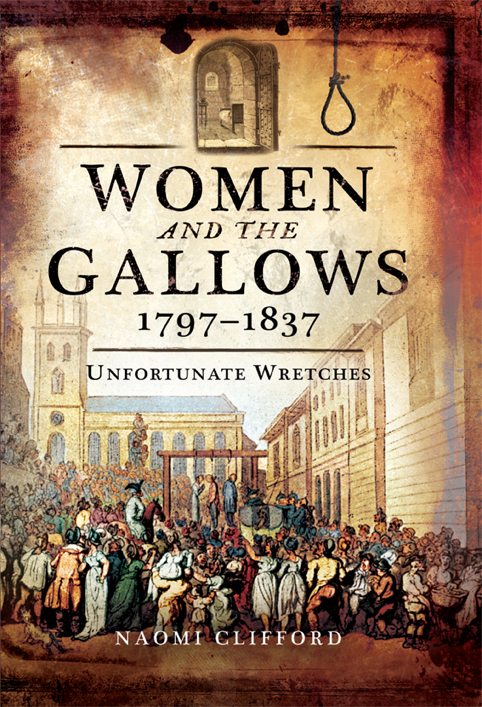

In the last four decades of the Georgian era, 131 women in England and Wales went to the gallows. What were their crimes? And why, unlike most convicted felons, were they not reprieved? ‘Unfortunate Wretches’ brings new insights into their lives and the events that led to their deaths, and includes chapters on baby murders among domestic servants, counterfeiting, husband poisoning, as well as the infamous Eliza Fenning case.

Mary Morgan – a teenager hanged as an example to others

Mary Bateman – a ‘witch’ who duped her neighbours out of their savings

Harriet Skelton – hanged for passing counterfeit pound notes, in spite of efforts by Elizabeth Fry and the Duke of Gloucester to save her

Eliza Ross – the so-called ‘female burker’, hanged for murdering an old woman and selling her body to anatomists

Plus, for the first time, all the stories of the women have been compiled in a unique directory.

Reviews

Times Literary Supplement, 22 June 2018

If I could get every single one of you to read this I would because I think it’s magnificent. –Lil’s Vintage World

1797 to 1837 were the years of the ‘Bloody Code’, with 188 capital offences on the English statute book by 1815, most of them added since the mid-18th century. Yet this was the ‘Age of Enlightenment’, when they no longer burnt heretics and hung witches or executed political prisoners, at least not in England! Why this sudden blood lust?

Admittedly most death sentences were commuted, but even so over 2000 people were hanged in this period, including 131 women. Perhaps this can be explained as a desperate reaction to the problem of social control with a growing and increasingly urbanised population in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution. With the advent of an organised police force and an expanded and better organised prison system, the Bloody Code was gradually unwound until only treason and murder remained capital offences.

Clifford lists all the female hangings in these 40 years, with a brief note on each and considers 20 of them in greater depth. Like searchlights, they light up corners of Georgian society which are otherwise hidden from history. –Edward James, historicalnovelsociety.org

This book was reviewed in JANE AUSTEN’S REGENCY WORLD’s March/April 2018 edition; the review piqued my interest. Clifford has written a book pulling out the stories of a group of women who were among the 131 female prisoners executed by hanging in the Georgian period between 1797 and 1837. She did not play sides; I would estimate half of the women whose stories she told in detail were obviously guilty and about half were likely or definitely innocent. The real crime, however, is that these women were sentenced to death while so many convicted of similar crimes were reprieved, acquitted, transported… The crimes, as Clifford notes, seem absurd to the modern reader, especially that the English gentry had made so many different things punishable by death. The legacy the book leaves with me is that poor young servant women were likely to be impregnated and abandoned; that left either a life of exclusion, shame, and poverty, or a life continued after the murder of the newborn illegitimate child. Georgian punishments were severe and quick, and in many instances, they should not have been. A very detailed exploration of the Regency’s criminal systems and the many flaws it contained. –Alethea, Good Reads *****

This fascinating and sobering book documents the circumstances of women sentenced to death by hanging from 1797 to 1837. Their crimes ranged from murder (poisoning was a popular method) to forgery of banknotes (a reminder that even minor crimes carried a sentence of capital punishment at the time). Some of the women seemed to be obviously guilty, while other cases heavily relied on circumstantial evidence or the testimony of more powerful witnesses. The cases of infanticide carried out by unwed mothers are particularly tragic – an illegitimate child (perhaps the product of a coerced relationship or rape) often meant the loss of not only social standing but also the opportunity to earn a livelihood, as few employers would accept a “fallen” woman under their roof, much less provide for the child. For those women who already lived hand to mouth, having a second mouth to feed was financially destructive and threatened their own survival. Many of the cases covered in the book reflect on the highly controlled and limited nature of women’s lives at the time and the little agency women had when it came to changing their situation: an unhappy marriage ended by poison, a needy infant silenced by neglect or murder, a debt settled by forgery. Of course, some of the accused appeared to be mentally ill; others seem to have acted with purely malicious intent. The book is divided into crimes against people and property with chapters devoted to more specific cases, making it an easy book to set down and pick back up without losing flow. A chronology at the end of the book presents summaries of each woman’s case and notes the relevant in-depth chapter. –Brooke, Good Reads ****

It’s a book that every public library, every university library and every secondary school library should own. There’s so much of interest not just about crime and punishment and the place of women in Regency England, but also the relations between servants and their masters and the ways people survived at the very margins of society. The law was pretty arbitrary, while the Bank of England emerges as very much the same institution as it is today, certain that its own interests are more important than the lives of mere humans. —Bruce Millar

Naomi Clifford’s accomplished account of the fate of 131 women sentenced to death by public execution between 1797 and 1837 is a grim, tragic and compulsive read. We enter the seamy back rooms of regency Soho where forgers lurked, the lives of con-women exploiting the superstitions of country folk and public executions that sated the blood-rush of a pagan past, occasionally resulting in the crushing to death of the spectators… This book is an important record, bringing to the surface the injustices of female victims killed by a world with little compassion. It is also an invaluable source for historical fiction writers. Naomi Clifford has given these voiceless forgotten victims a place in history, beginning with the Bank Restriction Act and ending with the ascension of Victoria. This period also brought about the end of public executions and a transformation in our capital punishment laws. It is easy though to be complacent – in exposing the legal injustices to women in the past we can be reminded of those in the present. Worldwide legal injustices against women still rage – and in our own country the present situation at Yarl’s Wood detention centre is unacceptable. A brilliantly researched document for our times. —Beatrice Parvin Read the whole review

Gripping and readable account of early 19th-century crime and punishment…. It is a horrifying, illuminating and compelling account that grabs the attention from the first page Jane Austen’s Regency World I read it in a single sitting and shines a welcome light into a dark era of British legal history. —Joceline Bury in Jane Austen’s Regency World.

Well-researched and presented in a readable narrative, the book touches on a wide range of themes, such as mental health, motherhood, social class and the history of criminal justice. These unusual ‘micro-histories’ provide a fascinating insight into women’s lives at the turn of the 19th century, especially those who fell foul of the law. —Angela Buckley in Who Do You Think You Are magazine

I love this book. In the last four decades of the Georgian era 131 women went to the gallows. What were their crimes? And why, unlike most convicted felons, were they not reprieved? This is a superbly written book, with an exquisite eye for detail, which brings new insights into the women’s lives and the events that led them to their deaths. Naomi Clifford writes riveting prose and is a serious social historian. The book is a culmination of a great amount of original research. The author has collected, for the first time, the stories of all the women executed in England and Wales between 1797 and 1837, and her book shines a spotlight on a neglected subject: previous works in this area have focused mainly on men. The book includes chapters on baby murder among domestic servants, attacks on employers by servants and the poisoning of husbands, and highlights the little-known death toll among women for property crimes, including passing counterfeit banknotes. Naomi Clifford brings the stories to life with great warmth, compassion and humanity and makes these historic events resonate with our lives today. —Amazon review

This is a great book for anyone who is interested in the criminology and life in the late Georgian era 1797-1837. Clifford tells the true stories of crimes committed by women, several of which are the extremely sad cases of infanticide, many of which leave you wondering whether, had they been tried today, would they really have been found guilty? As Clifford quite correctly says in her book, ‘late Georgian justice was swift and severe’. The book includes stories of murder, fraud, arson and poisonings, but it is interesting to note the crimes that people found themselves hanged for – sheep stealing committed by mother and son, she met her fate at the noose, but her son was transported. All crimes committed by women who met their fate, guilty or otherwise at the gallows. Many met the hangman’s noose for crimes which today we would consider relatively minor and yet, at that time men were able to commit rape and worse and receive a far more lenient sentence. Clifford carefully sets the stories in their historical context and her thorough research shines through. It is beautifully written and an easy read, despite the difficult subject matter. It is a mixture of quite well-known cases such as Mary Bateman, the so-called Yorkshire Witch and Eliza Fenning, who was hanged for attempted murder by poisoning, through to Charlotte Long, who was hanged for setting fire to hayricks. —Amazon review

This book is easy to read, interesting and explores Georgian/Regency attitudes to criminal women, the death penalty and social circumstances, especially the Bank Restriction act, which came in at the start of the period and saw a rise in forgery of small notes and a consequent increase in prosecutions and executions. A useful insight into women’s criminal acts and the response to these in the period covered. —Rosie Writes…

Well researched and presented in a readable narrative, the book touches on a wide range of themes, such as mental health, motherhood, social class and the history of criminal justice. These unusual ‘micro-histories’ provide a fascinating insight into women’s lives at the turn of the 19th century, especially of those who fell foul of the law. —Angela Buckley, in Who Do You Think You Are magazine, February 2018

Overall, the stories of these women tell us much about the world in which they lived. Most of them were poor and desperate, some were probably insane, and others such as Mary Bateman, the so-called “Yorkshire Witch”, died because in the dawning scientific age they managed to tap into a deeply rooted belief in sorcery and witchcraft.

This is a highly readable look at some women, some crimes, and, more particularly, at the mores of the last decades of the Georgian era. It’s well written and well researched. Ripperologist (Review by Paul Begg)