In the last post, I described how parish apprentice Frances Colpitts was apprenticed to tambour-makers Esther Hibner and her daughter (also called Esther). Mrs Hibner, Miss Hibner and their maid Ann Robinson were indicted for their cruel treatment of Frances and six other parish apprentices, who were rescued in February 1829 when Frances’s grandmother discovered them in an appalling state and called in the parish officers. Frances was taken straight to St Martin’s Infirmary where her condition was said to be critical. The investigation had revealed that another apprentice, 13-year-old Margaret Hawse, had been buried in secret by the Hibners the previous year. The magistrate Sir Richard Birnie had recommended the parish officers apply to have Margaret’s body exhumed.

An inquest on the corpse of Margaret Hawse took place on 18th February in the basement of The Elephant pub near Old St Pancras Church, with 12 jurymen and the Coroner, Thomas Stirling, in attendance. After his retirement Stirling later said that this one was among the worst he had seen.

The Coroner’s Jury viewing the murdered body of Margaret Hawse from John Fairburn’s chapbook of 1829 via http://www.lancet.com/

Hawse’s body was a “mere skeleton” and a surgeon, Mr Bellin, confirmed that the child had died of starvation. There was no surprise when the coroner’s jury concluded that Mrs Hibner was guilty of wilful murder and that her daughter was an accessory. Five days later they and Ann Robinson pleaded not guilty at the Old Bailey, but Peter Alley, the prosecutor, asked for a postponement of the trial as he had only just been given the brief. Mr Justice (Stephen) Gaselee agreed and moved the case to the next sessions.

The Morning Post commented on the appearance of Miss Hibner:

The younger prisoner is a remarkably fine young woman, and certainly looks incapable of committing the atrocious act with which she is charged.1

On 15th March, Frances Colpitts, who had been removed in a critical condition from the Hibners’ premises, died in St Martin’s Infirmary, and another inquest took place at The Elephant. The jury again found Mrs Hibner guilty of murder and Miss Hibner an accessory. It is unclear when the principal charge against the Hibners and Robinson was switched to the murder of Frances Colpitts rather than that of Margaret Hawse. Perhaps the prosecuting team felt that Frances’s case had more chance of success. Whatever occurred, the three women stood trial in front of Baron Garrow at the Old Bailey on 9th April 1829.

The surviving apprentices gave evidence against their former mistresses. Susan Whitby, Mary Ann Harford and Eliza Loman told the court about the starvation rations, overwork, punishments and abuse. Charles Wright, the surgeon, described the state in which he and Mr Blackman found Frances Colpitts and how the post mortem had discovered that she had abscesses in her lungs and tuberculosis. Thomas Gosling, another surgeon with long experience of treating workhouse patients, agreed that children of “diseased and weak parents” were more liable to consumption but that dipping Frances’ head in cold water had aggravated her underlying disease.

Mrs Hibner merely said: “I leave my defence to my daughter,” who said that, “My mother was a very good mistress to them,” and told the court that the apprentices would wet the bed two or three times a night and that her mother had borrowed £200 in order to feed and clothe them. Robinson said she never saw any of the ill-treatment described by the witnesses.

They called only one witness in their defence: John Steed, whose step-daughter was an apprentice, but he turned against them and said that when she came home on Sundays he could see that she was underfed and gave her food to take back with her.

The jury retired at half past six and after just over an hour returned a verdict of guilty against Mrs Hibner. The other two defendants were acquitted.

Baron Garrow addressed Mrs Hibner:

You were called upon by your duty to instruct and protect the infant who was committed to your charge. It seems that for some time you did pay, or seemed to pay, a degree of attention to the duty which your situation imposed upon you, but it was not very long before you began to manifest a want of feeling, for which there could have been no other foundation than a desire, by the utmost cruelty towards the poor unprotected infant who was under your care, to seek your own gain, by denying her the common necessaries of life; you saw her from day to day sinking under the most dreadful bodily exertions, and enduring sufferings that persons at a much more advanced period of life would have been unable to sustain. Although you have been the mother of a child yourself, you saw her sufferings without any of the feeling which one would imagine could never have been absent from a female breast. You are now to receive the sentence of death to which, by a course of lingering cruelty, you consigned an unoffending and an helpless infant. [….] You have now but a very very few hours to life, Let me then pray and entreat of you, as a fellow Christian and a fellow creature, to employ the brief interval which yet remains between you and eternity, in supplicating for that mercy hereafter which no human power can now afford you here.2

Hibner was ordered to be hung on Monday.

She showed no emotion, except when the judge said her body would be handed over to be dissected. Even when arraigned on the second indictment, the murder of Margaret Hawse, she remained stony-faced and pleaded not guilty with, as the Broadside later published described it, “all the firmness of conscious innocence, although as the poor child’s death had been the result of the same dreadful course of treatment adopted towards Colpitt, there could be no doubt of her legal and moral responsibility for the crime which had hurried the wretched being from the world.”3

As the prosecution had already obtained a guilty verdict against Mrs Hibner for the death of Colpitts, it was deemed unnecessary to conduct a second trial for the death of Margaret Hawse, but Miss Hibner and Ann Robinson were ordered to be detained for trial for assaulting her, Susan Whitby and others. The Chairman said he had fully expected Miss Hibner to be hung alongside her mother, but sentenced them to 12 months and four months imprisonment respectively. (After this point Miss Hibner and her siblings seem to disappear from the records, at least those available online. Perhaps they decided to live the remainder of their lives under assumed names.)

In Newgate Mrs Hibner continued to display “the most hardened disposition.” A report in the Morning Post4 claimed that she complained about the food and demanded mutton chops (she was refused and told that she could only have bread and water). The Reverend Cotton, the Ordinary of Newgate, advised her to read her Bible but she said she knew it already. She asked to see her daughter, who refused her, but then affected not to care (“It don’t signify”). Cotton managed to persuade Miss Hibner to change her mind and she arrived in the cell at 2 o’clock but the meeting at first was “cold and indifferent”, with the mother and daughter behaving like “perfect strangers”. They shook hands and then bonded with some “most abusive vituperations against the witnesses.” “Well, all I am sorry for is that I did not rush from the dock, and tear the wretches to pieces,” said Mrs Hibner and her daughter “wept bitterly” when their 30-minute meeting was over.

At about four o’clock on Sunday, Mrs Hibner made an attempt at self-harm. In the privy she jabbed at her throat with a blunt dinner knife she had hidden in her stockings, and later admitted that she had done so in order to delay her fate and not to kill herself. She was put into a straitjacket, and wearing this over a white cotton bedgown over a black stuff petticoat she was led out at 7.45am on Monday morning to the gallows.

There was a large crowd, the majority of them women. It had been over 60 years since a woman had been executed for a crime against children of this enormity. In 1767 Elizabeth Brownrigg, a midwife and the mother of 16 children, killed her 14-year-old servant Mary Clifford, an apprentice from the Foundling Hospital. After trying to run away, Mary was kept naked, forced to sleep in a coal hole, beaten while chained to a roof beam in the kitchen and fed on bread and water. After neighbours alerted the Foundling Hospital, Brownrigg and one of her sons went on the run but were soon captured. By the time they stood trial at the Old Bailey, Mary Clifford had died of her infected wounds. Brownrigg was hung at Tyburn.

Like Brownrigg, Hibner was condemned and abused as she made her way to the gallows, where William Calcraft, the newly appointed executioner for London and Middlesex, wagged his finger at her and pointed down to Hell. Calcraft favoured the short drop, during which the condemned were slowly strangled, sometimes flailing for several minutes. On occasion he would be forced to pull on their legs or push their shoulders down. The crowd cheered loudly as he put the noose over Hibner’s head and the noise as she dropped was deafening. Her body was left to swing for an hour and was then cut down and given to Guy’s Hospital to be dissected by Dr Bright.5

That was not the end of cruelty to parish apprentices, however, nor was it the end of Hibner’s infamy.

Less than a month after she was executed, “A Country Clergyman” wrote to the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette called for the end of the system of binding apprentice, comparing it to slave labour. Her crimes were used as a marker by both supporters and opponents of slavery.

The sooner the Apprentices are emancipated the better; and whilst our Philanthropists are anxious to do away with negro slavery, I would beg to call their attention to a system of domestic slavery, pursued at home, and which ought immediately to be corrected.

The correspondent anticipated that a memorial would be presented to the Prime Minister, Robert Peel, and that a delegation of MPs from the western counties would request an investigation, and that a Bill would be brought before Parliament to abolish the system.6

Even as “A Country Clergyman” was composing his letter, another case of cruelty towards an apprentice came to light. The Stamford Mercury reported on 1 May 1829 that the town of Alford had been “for several weeks in a state of excitement” over the case of a young woman whose treatment echoed Frances Colpitts’. The 12-year-old victim, who was apprenticed to a mantua-maker, was not expected to live after “a series of ill-treatment and want of air and exercise”. The magistrates were investigating. The authorities in Staffordshire may have been especially sensitive on the issue. Four years previously, Mary Limer, a dress-maker of Uttoxeter was sentenced to 12 months imprisonment for her “almost unparalleled barbarity” towards her apprentice.7. That case conjured up another painful and notorious case, of Charles and Hannah Squire who were charged in 1799 with the murder of Joseph Green, their parish apprentice. 8 Green died from “debility and for want of proper food and nourishment, not from the wounds he had received” but as it was not the wife’s duty to provide food, “she being the servant of her husband,” Hannah was acquitted while her husband was found guilty and executed.

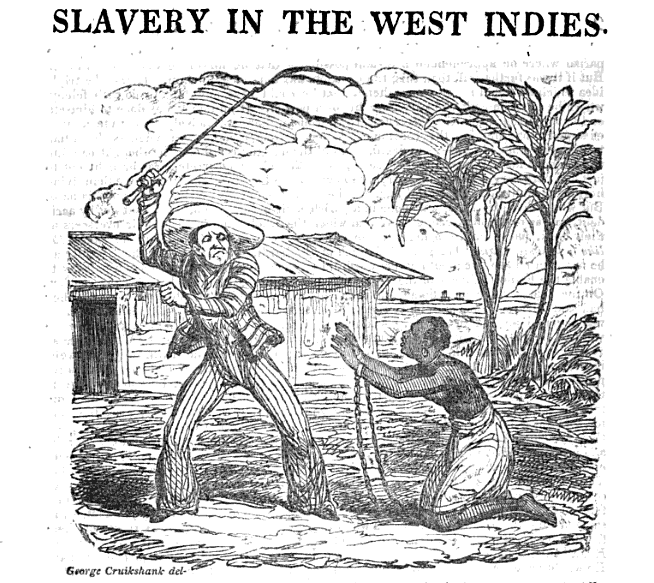

It is not possible to quantify cruelty towards workhouse apprentices. It is likely that only the most serious, or obvious, cases came to the attention of the authorities. The Hibners’ crimes achieved a high level of notoriety partly because the crime involved only females, but also because the punishment given to Mrs Hibner was directly compared with that imposed on Henry and Helen Moss in the Bahamas. In 1827 the Mosses were charged with the death of their house slave Kate. For theft and disobedience they had put Kate in the stocks for 17 consecutive days and ordered her to be be repeatedly flogged. After her release, while feverish, she was made to work in the fields, where, after further beatings, she died. A Grand Jury declined to find a “true bill” for murder against the Mosses and they were instead charged with misdemeanours, found guilty, ordered to the common jail in Nassau for four months and fined £300. Theirs was a sharp contrast to Mrs Hibner’s fate.

Slavery in the West Indies, republished from The Westminster Review, No. XXII, 1 January 1830. Illustration by George Cruickshank

The Mosses had a great deal of support from among the establishment, with many praising their “general kindness” towards slaves and their respectability. Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country 9 claimed not to comprehend the sympathy shown to slaves, who were, apparently well fed and cared for while labourers in England, parish apprentices among them, were starved and beaten for no good reason.

Bizarrely one who was especially warm on the contrast between slaves and the exploited apprentices was Edward Gibbon Wakefield10 who had achieved his own notoriety by abducting a 15-year-old heiress and marrying her against her will (he was sentenced to three years in prison). From his home in Australia, he opined on the plight of the apprentices pointing out in a chapter titled “The Misery of the Bulk of the People” that children were available for sale in America as slaves for £50, while in London they were given away for £10.

Did the system of parish apprenticeships change or end after Hibner was hanged? No, although some individual parishes or parish officers may have become more vigilant when giving young children into the custody of masters and mistresses. In 1834, the Poor Law Amendment Act made poor relief appreciably harder to access (parish funds were only available to paupers who were prepared to enter the workhouse where, in order to discourage all but the genuinely destitute, conditions were only just tolerable) and workhouses were now grouped together in Poor Law Unions, supervised by locally elected Boards of Guardians. In 1844 the central authority of the Poor Law Union was given control over parish apprenticeships and empowered to make regulations prescribing the duties of employers 11. Poor children continued to be farmed out to industry or the military, or in the case of girls into service, in order to be taught a trade and remove them from parish responsibility as soon as was feasible.

No doubt, legislation such as the various Factory Acts and Mines and Collieries Act (1842) helped to increase the public’s awareness of the issues around child labour as did notorious cases such as that of Frances Colpitts and her fate at the hands of the Hibners. But in the end, the reason parish apprenticeship declined was that methods of manufacture became more efficient, to the point where adult workers’ productivity outstripped that of children.

Indenture has not gone away, it has merely gone to ground as trafficking and modern slavery. Frances Colpitts and her like are still stark reminders of its brutal reality.

- 24 February 1829.

- Evening Mail, 13 April 1829.

- Broadside/Newgate calendar.

- 14 April 1829.

- The Lancet, 1828–1829, Vol II, page 158.

- 2 May 1829.

- Stamford Mercury, 22 July 1825.

- Henry Roscoe, A Digest of the Law of Evidence in Criminal Cases. Philadelphia, T. and J. W. Johnson, 1840.

- July 1830.

- England and America: A Comparison of the Social and Political State of Both Nations, 1834.

- English Poor Law Policy, Sidney and Beatrice Webb.

Leave a Reply