This gruelling and gruesome story of the exploitation of defenceless friendless children 200 years ago still has the power to shock, not only in the pathetic details of the suffering of young people in servitude but also in the failure of the authorities to take real and timely action in its wake.

Frances Colpitts (sometimes Colpit or Coulpit) was born into a poor family in the parish of St Martin in the Fields in Westminster in 1819. As a young child she was orphaned or her parents were otherwise unable to care for her and she was handed into the custody of the overseers at Castle Street Workhouse, who sent her to their infant poorhouse at Highwood Hill in Mill Hill, north London.

It cannot have been an idyllic childhood, but Frances would have been reasonably well fed and kept as safe and warm as the parish was prepared to pay for. She was probably put to work at Highwood, as soon as she was old enough, helping to care for the younger children.

Frances was not totally without family, however. Her maternal grandmother, Frances Gibbs, after whom she had been named, kept in touch and visited when she was able. Mrs Gibbs was probably relieved when her granddaughter, at the age of nine, returned to Castle Street Workhouse in late 1827 as it meant she no longer had to travel up to Mill Hill to see her.

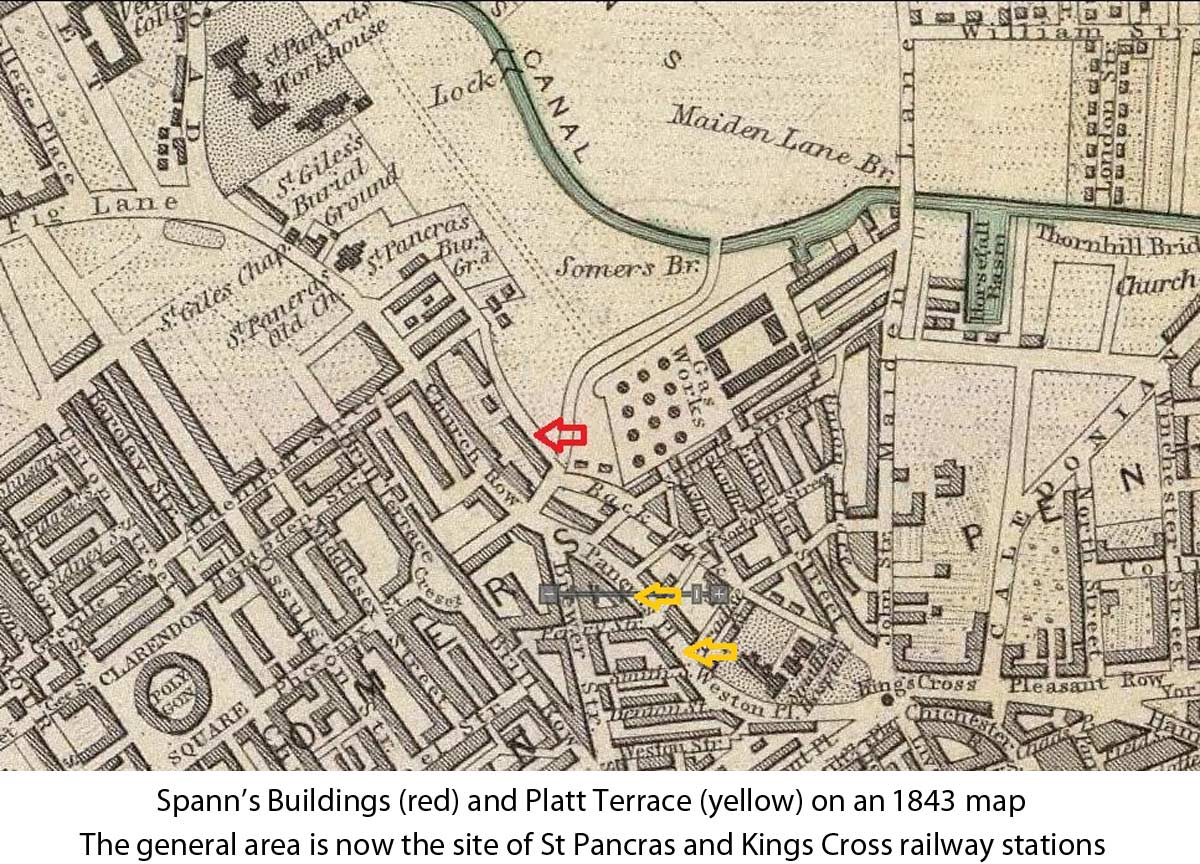

At some point Mrs Gibbs gave Frances a dress, petticoat and green baize cloak, probably after her return to London and before the child was due to start her apprenticeship to Esther Hibner, a widow of about 60 involved in the business of tambour-making at her premises at 13 Platt Terrace off St Pancras Road1. Frances was taken “on liking”, meaning that there was a probation period of three weeks, during which both sides would see if they were suited and, if all went well, Frances would sign the indenture papers in front of a magistrate and would be bound to Hibner for seven years. In return for feeding, clothing and housing Frances, the parish would pay Hibner a premium of £10. It was a mutually beneficial system. There were no wages for Frances and Hibner would have the benefit of the child’s labour. The parish, meanwhile, was able to shed its financial obligations towards her. Although in theory Frances had to give her consent, in reality she and her grandmother had little say in the arrangement or power to change it.

George Cruikshank, Oliver Twist: “Oliver plucks up a Spirit”

The system of parish apprenticeship will be familiar to readers of Oliver Twist (published 1837-9), which Charles Dickens subtitled A Parish Boy’s Progress. Indeed, Frances’ trajectory to this point has many similarities to the fictional Oliver Twist’s. After having been in the care of a baby farm, and returning to the workhouse where he is half-starved, Oliver is indentured to an undertaker, whose wife mistreats him. Not all parish apprentices were abused but few checks were made on the conditions they were sent into or their welfare after they left the workhouse. The potential for disaster should have been obvious, especially in the industries that were known for their ill-treatment of juvenile indentured labour.

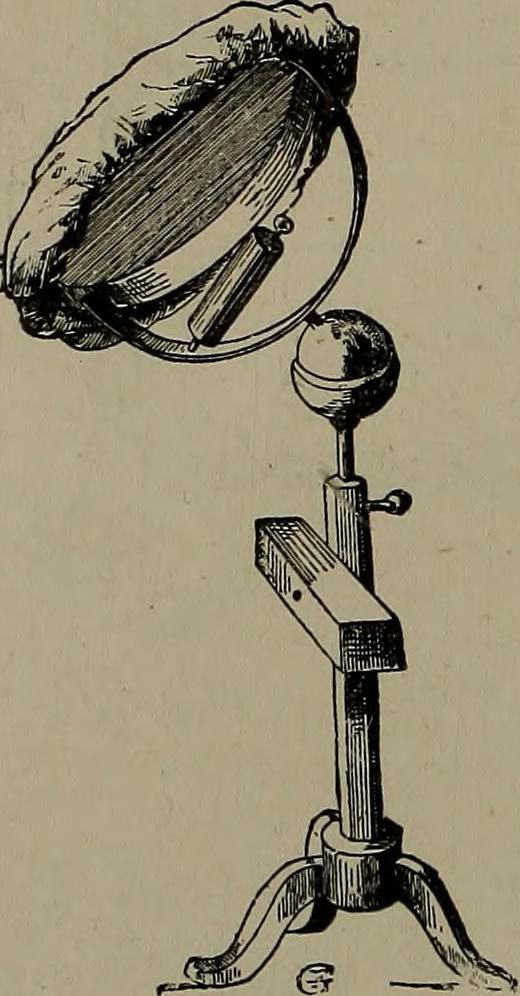

Tambour embroidery frame, from Embroidery and Lace by Ernest Lefébure and Alan S. Cole. London: H. Grevel, 1888

One such was tambour-making, the trade Frances was now apprenticed to. Tambour-making involved embroidering and embellishing Brussels or Nottingham net which was stretched over a frame. Small-scale tambour workshops proliferated across London and, as a result, competition between them was fierce and conditions for the workers harsh. An extreme case of ill-treatment of tabour apprentices came to the attention of the authorities in 1801.

A Mr Jouvaux, a Stepney tambour-worker, was sentenced to a year’s hard labour for his cruel treatment of 17 female apprentices. Susannah Archer, aged 15, whose case formed the indictment, was “famished almost to death” and five other apprentices died prematurely, which was attributed to Jouvaux’ harsh treatment. All of the girls were beaten regularly. They were allowed no meal breaks: their meagre rations were instead brought up to them while they worked at their frames. At times they were so hungry they ate from the pigs’ trough or kind neighbours took pity and gave them what they could afford. Mr Justice Grose, while upbraiding the defendant, also blamed the parish officers for their negligence2 but this case did not lead to any improvements for parish apprentices and, more than 25 years later, Frances had the misfortune to enter a world with absolutely no protection of her rights. Frances would have been utterly unaware of these dangers when she arrived at Hibners’ premises in Platt Terrace.

At first all would have seemed, if not fine, pretty much as she might expect. Frances would have been introduced to Mrs Hibner’s daughter, also called Esther, a woman in her early 20s who had a child, and the general servant Ann Robinson, a young woman whose job it was to assist her mistresses and manage the workers. No doubt, Frances would have been relieved to see there some familiar faces from Highwood Hill and Castle Street. Of the six other apprentices, who were aged between six and ten, five came from her own parish of St Martin’s, including Mary Ann Harford, her senior by a year, who had also been at Highwood Hill as a young child, and who had been apprenticed to Hibner a few months previously. Two were from St Giles Without Cripplegate in the east of the city.3

Frances was bound on 29th April. The work was hard but there was just about enough food. Then conditions took a steep downward turn.4 After October, the apprentices were given almost nothing to eat. The winter was especially cold but the apprentices, who slept in a huddle on the floor of the workshop, were protected only with a thin blanket. They wore their clothes to bed (Frances wore the clothes her grandmother had given her). They had no stockings and no clean linen. Every day they were woken at 2 or 3am and worked until 10 or 11 at night. Breakfast was a five-minute break for a slice of dry bread and watered milk but on the days when a dinner of potatoes was served there was no breakfast. There was meat once every two weeks. The worst of it was that if the girls did not produce enough tambour, they were fed nothing. Sometimes they were so hungry that they stole bits of fish and bone from the pigswill brought in for the dog by Hibner’s son. One of the apprentices said later that Frances would even eat candle ends and grease.

The privations the girls endured were appalling, but they were crowned with extreme physical abuse. For not working fast enough all three of her mistresses beat Frances with a rod, cane or slipper, or knocked to the floor with their fists. She developed abscesses on her feet. On one occasion, when ordered to clean the stairs, she fell to the floor. Then she was hauled upstairs and beaten “under her clothes”. When she was sent back to the stairs to continue cleaning she wet herself and the younger Hibner pushed her nose into it, afterwards holding her up by the heels and plunging her face first into a pail of icy water, with Robinson shouting “Curse her, dip her again, and finish her.” Frances later told the other girls that she was “ill in her inside”.

Frances may have been acquired as a replacement for Margaret Hawse (or Howse), who had become sick and died in the house earlier in the year. Complaining of headache, underfed and exhausted, she had gradually become so weak that one morning she was unable even to get out of bed. When Ann Robinson dragged her upstairs and tried to make her stand, she collapsed. Eventually Mrs Hibner pushed her downstairs to breakfast, where she lay on the floor.

“Let her lay there and die; she will be good riddance,” said Mrs Hibner.

Margaret stopped talking and died at 7am the next day.

That evening the Hibners and Robinson participated in a macabre celebration. After a good dinner of meat and pudding they toasted Margaret’s death with a pint of gin. Meanwhile, two of the apprentices were given the task of washing and laying out Margaret’s body, a job more usually done by “searchers,” middle-aged women of the community whose job was to report on cause of death. The Hibners could not risk anyone outside the premises seeing the state Margaret died in, so they bought a coffin and nailed Margaret into it before having it carted off to the undertaker, Mr Hamp, who later said that he peeked in to check and saw an emaciated child but assumed that she had died of tuberculosis.

Frances’ grandmother Frances Gibbs visited every few weeks but after a while she was refused at the door. In late September she was told that another daughter of Mrs Hibner’s had died (this was true) and it was not possible to see Frances. On 3 January, she was told that the girls were “being washed” and could not see visitors. A few months later, Miss Hibner told her that Frances had spoiled her work and was being punished. Eventually, on 11 February, Miss Hibner told her, “You will see a pretty thing when you do see her, she is in a deplorable state,” and told her that the child had been ill. Gibbs did manage to gain admittance and what she found shocked her profoundly. She went straight to the Castle Street workhouse to report the situation and returned the following day with the overseer, John Blackman.

He later described the scene. Frances was on a filthy mattress on the floor, covered only with a small woollen cloth. She was emaciated, covered in bruises and her feet were “mortified,” with the toes dropping off. Blackman insisted on taking the girls to the workhouse, but Mrs Hibner resisted. He came back the next day with Charles James Wright, the parish surgeon. He and Blackman took five children of the children back to the workhouse but Frances was taken straight to St Martin’s Infirmary and Susan Proctor to St Pancras. Frances was, said the doctor later, “merely skin and bone, her lips contracted a great deal, the teeth much exposed, a redness about the eyes.” She was not expected to live.

Blackman had counted the children and worked out that one was missing. At the house, the girls told him that Margaret Hawse had gone to her aunt in the country but he strongly suspected that they were lying. After they were removed from Platt Terrace, they told him that they feared the Hibners would flog them and keep them without food if they told him the truth. They described how Margaret had died and was buried in secret.

Four days later the Hibners and Ann Robinson were brought before Sir Richard Birnie at Bow Street Magistrates and charged with extreme cruelty towards a number of female paupers and starving them almost to death.

The magistrate was particularly upset to hear evidence that Frances’s face was forced into her urine.

Miss Hibner interjected. “The truth is, Sir, she wet the bed repeatedly, and I rubbed her nose in it.”

“You had better say nothing for you are doing yourself no good,” replied Birnie.

Birnie committed the prisoners and recommended the parish officers apply to have the body of Margaret Hawse exhumed as soon as they could.

- Esther Hibner, born Esther Read, was the widow of John Ellis Hibner, a butcher. The couple had at least five children.

- Ivy Pinchbeck, Women Workers in the Industrial Revolution. Routledge, 1930; Morning Chronicle, 24 June 1801.

- This was Esther Hibner’s own birthplace and she probably had connections with the workhouse overseers there.

- Quite apart from this change, the girls later reported that while the apprentices were “on liking” the food was, if not plentiful, at least reasonable but got worse abruptly after they had signed the indenture.

Leave a Reply