I want that pretty frock, Miss Dombey,” said Good Mrs Brown, “and that little bonnet, and a petticoat or two, and anything else you can spare. Come! Take ’em off.”

Florence obeyed, as fast as her trembling hands would allow; keeping, all the while, a frightened eye on Mrs Brown. When she had divested herself of all the articles of apparel mentioned by that lady, Mrs B. examined them at leisure, and seemed tolerably well satisfied with their quality and value.

“Humph!” she said, running her eyes over the child’s slight figure, “I don’t see anything else—except the shoes. I must have the shoes, Miss Dombey.”

Poor little Florence took them off with equal alacrity, only too glad to have any more means of conciliation about her. The old woman then produced some wretched substitutes from the bottom of the heap of rags, which she turned up for that purpose; together with a girl’s cloak, quite worn out and very old; and the crushed remains of a bonnet that had probably been picked up from some ditch or dunghill. In this dainty raiment, she instructed Florence to dress herself; and as such preparation seemed a prelude to her release, the child complied with increased readiness, if possible.

—Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son (1848)

In the later part of the 19th century the crime of child-stripping, so vividly depicted by Dickens, was the subject of a “moral panic”. Elderly old crones, it was believed, were capturing well-dressed children, removing their apparel and abandoning them in dirty and dangerous neighbourhoods.

As so often, there was truth behind the urban myth. Child-stripping did happen. However, according to research by Donald M. Macraild and Frank Neal, most perpetrators, in the Victorian period at least, were not elderly women but young females, many scarcely older than the unfortunate siblings in whose care the stolen babies or toddlers were often entrusted.

1Macraild and Neal’s analysis of newspaper reports shows that cases of child-stripping reported in newspapers and courts rose from around 10 a year between 1820 to 1830 to a peak of over 60 in the mid-1850s.

There can be no doubt that the crime was severely under-reported. Many child-stripping incidents never came to the attention of the authorities, either because the thief was not caught, the families distrusted the police or the child victims were too young to give evidence.

It took only a few minutes with a child to remove its clothing, depart for the nearest old-clothes dealer and take off to a cookshop or pub. I looked at the 30 cases of child kidnapping by women prosecuted at the Old Bailey between 1800 and 1837 and published on Old Bailey Online. Before 1814 kidnapping was not a felony offence but a misdemeanour. Thereafter, taking a child under the age of ten by force or fraud was a felony.

In two-thirds of the cases, theft of the clothes was a clear motive.

Eliza Harris was indicted for kidnapping “by force” two-year-old Ellen Bonsey who was playing by the door of her home in George Court off the Strand on 5 March 1830. There were three alternative charges, to make sure something stuck. The first of these was the same as the primary charge but “by fraud”, the second detailed the goods stolen “by force” (1 pinafore, value 3d.; 1 frock, value 4d.; 1 hat, value 6d.; 1 petticoat, value 2d.; 1 shift, value 2d., and 1 pair of boots, value 4d.); and the third was the same but stolen “by fraud”.2

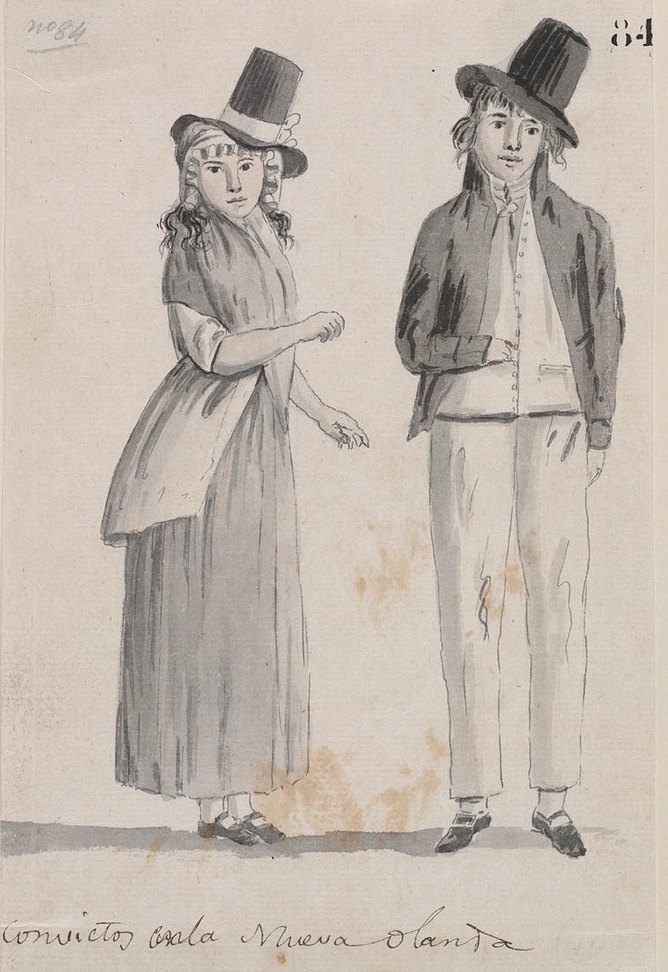

The act of stealing a child to strip its clothes was usually opportunistic rather than premeditated. Even so, the perpetrators must have calculated the benefits of making off with a small, portable child who could not give evidence later but wore smaller, less valuable apparel against the risks of taking an older one, who might yield a good return but who would be likely to resist verbally or physically and attract the interference of the public. The child victims in the 30 Old Bailey cases ranged from six weeks to six years, with most of them babes in arms or toddlers. In 1821 25-year-old Glaswegian Matilda Dowd, barely four and a half feet tall herself,3 chose to carry off five-year-old Louisa Smith from Queen Street, Clerkenwell. She was challenged by George Hart, a painter, who became suspicious because he heard Louisa crying and complaining that she wanted to go home. After a constable became involved, a crowd gathered sending up a cry of “Rescue!”. At the Old Bailey Matilda received the standard sentence for kidnapping – transportation to Australia for seven years.4

Child-stripping was generally a crime of the poor on the slightly less poor, and often of the inebriated. Elizabeth Gurnett, 30, a servant in a public house,

5was drunk when she snatched two-year-old Jane Sarah Mouatt, the daughter of a poor tradesman, for her frock, petticoat, shift, stockings and half-boots. As Gurnett passed East India House in Leadenhall Street she was stopped by a crossing-sweeper.

It [the child] was crying – it struck me, from its appearance, that it did not belong to her.

I said, “My good woman, where are you going with that child?”

She said, “What is that to you? Mind your own business.”

I said I considered it my business […] I said I was fully confident, from its respectable appearance, that it did not [belong to her]. I took it up in my arms — she said if I offered to take her child away she would be d—d if she would not split my nose.”

Gurnett claimed in court that she had found the child wandering in the Minories and had no intention of stealing her. She too was sentenced to transportation for seven years.

6The penalties were harsher for repeat offenders. Mary Jones was given transportation for life for taking three-year-old Ellen Goddard (wearing a bonnet, pelisse, frock, petticoat, stays, shift, and tippet) in January 1829 during her mother’s momentary inattention while shopping. The court heard that she had previous felony convictions.

Some children were taken in order to earn money for their kidnappers. In 1817 26-year-old Ann Lee took a two-year-old child to add to her appeal while singing in public houses. The child’s mother described the moment she confronted Lee:

I received information, and found the prisoner with my child at the Royal Hospital public-house. It had two songs in its hand – the prisoner also had songs.”

In the Old Bailey records I reviewed, there were only two cases of child kidnapping by men, and both of these involved taking children to become chimney sweeps.

The suspicion that gypsies steal children to exploit them for money was (and in places still is) a persistent one.

7In 1824 the Leicester Chronicle8 gave an account of the disappearance of four-year-old James Thorpe, the son of ship’s carpenter Thomas Thorpe of Blackwall in south-east London. It was feared that he had followed his father to work at the river and fallen in the water until a local barmaid told James’s mother that she had seen him with a strange woman and a tinker who was later traced to London. The tinker told Mr Thorpe that the woman was Margaret Parker, who had left the gang she had once belonged to and turned to kidnapping and ransoming children. Any unclaimed children were handed over to her old confederates, who “put them to the torture” until they became accomplished acrobats able to make money on the roadside. Mr Thorpe and a police officer eventually found the boy in a state of emaciation in Fox’s Court, St Giles’s, one of the poorest areas of London. Parker was not at home and, stated the newspaper report, she therefore escaped arrest. How much of this tale is true is impossible to say, as no prosecution seems to have arisen from it.

In 1832 the Evening Mail reported that two girls aged 13 and 15 were abducted by Gypsies on their way home from the illuminations in Bristol.9 The fanciful allegations of 13-year-old Charlotte Savage (which may not have been her real name) who told magistrates in Brighton that she had been taken by the Gypsies, prevented from leaving and made to travel the country with them alongside a boy who was kept in chains, were viewed with scepticism. The Gypsy family were vindicated and judged to be both respectable and truthful. Charlotte, however, was charged with the theft of a bonnet and shawl and remanded, her credibility destroyed.

10Not all children were stolen for their clothes or for their earning potential. Throughout history they have been abducted to fill an emotional and psychological void. That may be the deep desire to care for a child, or it may be in order to maintain a fragile adult relationship. Samuel Shrier, the nine-year-old son of a night constable in Mile End, east London, went out to play in the fields near Bancroft’s Almshouses

11with three of his younger brothers, including 14-month-old Benjamin, who was wearing a hat. Unfortunately, 20-year-old Mary Ridding, dressed in a white gown and straw bonnet and carrying a bundle, spotted them and offered Samuel a shilling to get three pennyworth of cakes in the Mile End Road. He returned within a quarter of an hour but Mary was long gone. At the Cross keys in Gracechurch Street, Esther Gilder, a chambermaid, helped Mary look after Benjamin, who was unhappy. As Esther later told the court, he “looked very pale, and fretted and pined a good deal. [He] appeared to want the breast,” and that she noticed that Ridding treated him with “great tenderness.” The child was eventually located at lodgings in Birmingham. Ridding was married to a Captain in the 59th Regiment, who had sent her home from India. She had told him that she was pregnant and later that she had given birth to a baby on the journey home. At the time she committed the crime she lived in Birmingham – she travelled to London in order to acquire a child whom she planned to present to her husband as her own. In 1811 Thomas Dellow was similarly the target of a woman keen to present a child to her husband. I have told the story of his abduction and restoration to his parents elsewhere on this site.

One day in June 1817 the six-month-old son of Henry Porter, a butcher of New Quebec Street, Portman Square was decked out in a beaver hat and feather, cloak, frock, petticoats, shirt, cap, and socks (total value 15s 6d) and placed in the charge of the family’s 14-year-old maid Louisa Wood. Louisa was passing the time of day in the street with two other servants who were also caring for children when the grandly named Harriet Molyneux Hamilton, aged 45, approached and offered her sixpence to run an errand, with the promise of another on her return. Harriet persuaded Louisa to leave the baby with her, then as soon as Louisa had turned the corner rushed off with Henry in her arms towards Paddington Street, jumped in a hackney carriage and commanded the driver, Thomas Woolhead, to head for Elephant and Castle and then for Croydon. Along the way the kindly Woolhead bought milk for the child and food for Harriet and at Croydon innocently saw them in to a carriage to Reigate. On his return to London he was appalled to learn that a child was missing and that he had helped Harriet escape. He immediately went to Mr Porter and drove him and his father to Croydon and then on to Brighton. They eventually found Harriet and the baby in Chichester, 83 miles from London.

Unlike Charles Rennett, who in 1818 stole three-year-old Charles Horsley from his nursemaid to punish the child’s father,12 none of the women I investigated were accused of stealing children for the purpose of revenge.

For any parent of a missing child the search – and the wait for news – is agonising. Although the Old Bailey records are truncated and the reporting bald, even abrupt, we can get a clear idea of the pain and grief of the bereft parents and learn something of the measures they took to try and find their children. Help was minimal: they would have to do most of the work themselves. First they would search the surrounding streets and speak to neighbours; if that yielded no results they alerted constables and nightwatchmen; and if the child still was not found they distributed handbills and advertised in newspapers. Poverty or a large number of other children did not assuage their feelings of loss. In the Old Bailey cases, only one child was never found: James Burke, aged 10 days, whose mother Ann was accosted by a woman while taking a rest on her journey to the St Giles workhouse to seek medical assistance. The woman was aged about 25 with a mark under her eye. Over the next few days she ingratiated herself with Ann, giving her money and presents of flannel and wine and taking her to the pub. On the day James disappeared, the woman gave Ann money and sent her out for food while she held the baby. That was the last Ann saw of him. When she recognised woman five months later in Newgate market she challenged her, gave chase when she ran and eventually cornered her in a baker’s shop, but before long found that the tables had turned. She was accused by the woman, who was called Mary Edginton, of extortion and hauled before the magistrate at Guildhall and sent to the Compter. Eventually, however Ann and her husband, a poor dealer, took Edginton to court. The case, however, was not successful and Edginton was acquitted.

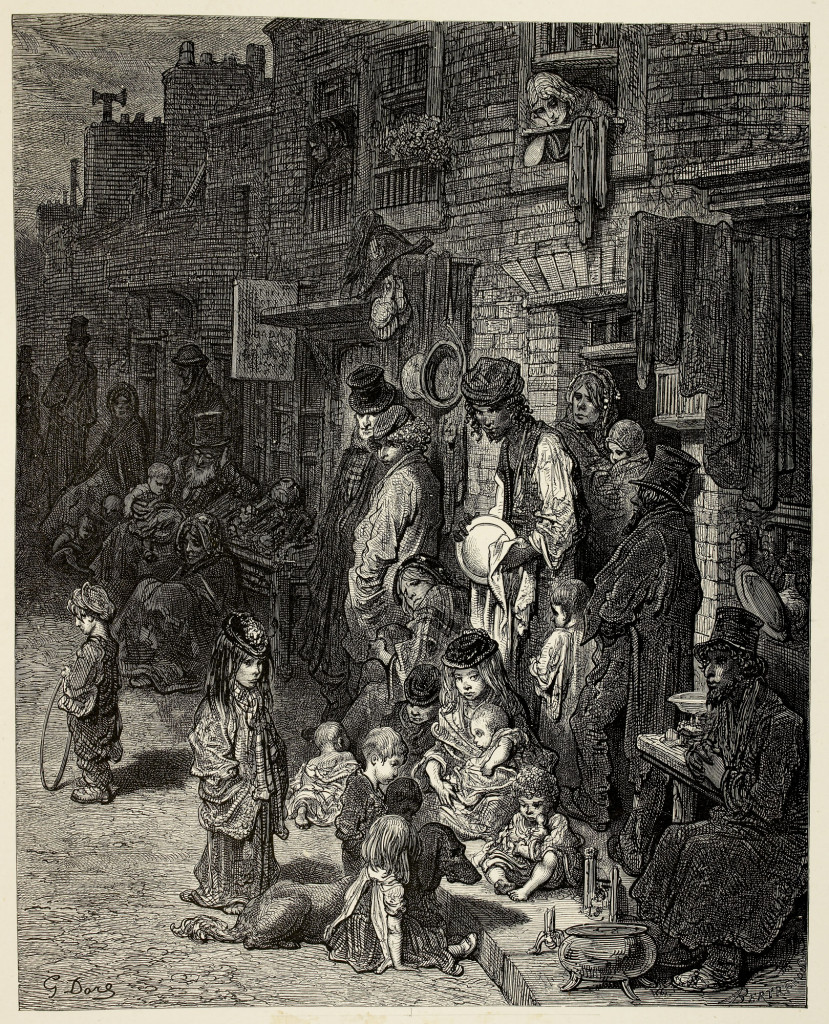

13What is striking in many of the cases of child stealing is that despite the anonymity of the urban landscape, the teeming slums and overcrowded streets, people knew their neighbours and recognised the children. It was an age where your clothes defined your rank the public were unafraid to intervene when they saw women with children who looked richer or more well cared-for than you might expect. When children went missing, word spread fast and, perhaps to our surprise, many were found and restored to their relieved parents.

See also Two cases of child stealing.

Postscript: My research into women who were hanged in the late Georgian era included the case of Eliza Ross, the last person and the only woman convicted of ‘burking’ – murdering to provide cadavers for anatomists. Thirty-three-year-old Ross was hanged outside the Old Bailey on 9 January 1832. In amongst the highly prejudicial information about her that was published on the day of her execution, along with her description as a ‘large, raw-boned coarse-featured Irishwoman’ and claims that she sometimes worked as a porter ‘for which her masculine proportions and strength well qualified her’ was that she ran a sideline in cudgeling cats to death and decoying children in order to steal their clothes.

You can read more about Eliza and the 130 other women who went to the gallows in Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches.

- Donald M.Macraild and Frank Neal, Child-stripping in the Victorian city, Urban History, Volume 39, Issue 03, August 2012, pp 431-452.

- The records do not state which of the charges the defendant was found guilty of.

- Dowd is described in her Certificate of Freedom as 4 feet 8¼, fair, with freckles; originally from Glasgow

- In May 1822 Matilda arrived in Hobart, Tasmania, where she was indentured as a servant.

- State Archives NSW; Series: NRS 12189; Item: [X634]; Microfiche: 702

- Gurnett married John Daft Mellson in Windsor, New South Wales in 1839 (State Archives NSW; Series: 12212; Item: 4/4510).

- In 2013 there were two cases of Roma couples being accused of stealing children that later turned out to be their own

- 9 October 1824

- 26 December 1832.

- Brighton Gazette, 21 January 1836. The trail goes cold and I cannot find out further information about Charlotte.

- Endowed by Francis Bancroft in 1737, the Almshouses and school were opened on the north side of Mile End Road.

- Rennett felt that Mr Horsley, to whom he was related, had unfairly benefited from a will.

- The Examiner, 16 January 1825.

There’s more on misjudged Gypsies at All Things Georgian: https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2014/07/15/misjudged-gypsies/

I hadn’t read this article before: very interesting. I was particularly interested in the reference to the Bancroft Almshouse – this was actually closed in 1884 and a new school opened in Woodford Green. I went to that school in the 1950s. Glad to see it wasn’t the poor, maligned gypsies at fault. A rhyme we children learnt when we were very young started: “My mother said I never should play with the gypsies in the wood…” – it goes on to describe the horrible consequences, but fortunately, I’ve forgotten all that part.

Thanks for your comment, Robert. Yes, gypsies never seem to get the benefit of the doubt!

Thank you for this very interesting article. I have an ancestor who was transported to Van Diement’s Land in 1834 for abducting a child, stripping her clothes and stealing a bonnet and several buttons. Her name was Norah Harris, and she later made a life for herself under a new name and identity in Tasmania. The only information I have on her trial is a brief report in a London newspaper, and a record on Ancestry.com of her sentence. She was sentenced in April 1834, and sailed on the New Grove in November 1834, so she had to wait only a few months in prison. I live in Canada, so I don’t access to the London Metropolitan Archives, and I am wondering if I might find more information about her trial there – she was tried at the Middlesex Sessions, so I assume not the Old Bailey. I’d like to know, specifically, if this was her first offence or was she a repeat offender. I wonder if you have any thoughts on this.

I wonder, also, if you know how much delay there might have been between arrest and trial? We know nowadays there are often long delays, but were trials more speedily arranged in the 1830s? The reason I wonder about this is this. Her mother died in 1827, and her father remarried in May, 1833, one year before her trial. However, her father’s marriage banns were read in June and July 1832 – almost a year before he and his new wife married (by which time they already had a child!) I’ve wondered about this long delay between the banns and the marriage (usually marriage took place three months after the banns). Could the delay have been because of Norah’s troubles with the law? Could she had been arrested in, say, late 1832, but not tried until April 1834. If so, that would be a delay of well over a year between arrest and trial, which seems excessive for the 1830s. Of course this is speculation, but if her arrest caused a major crisis in the family, that might have resulted in delaying her father’s marriage.

Anyway, thank you again for your interesting research work.

Hello Christine – Thanks for your very interesting comment and kind words. Just to clarify: Whereas in other counties the more serious criminal matters were dealt with in the Courts of Assize, in Middlesex they were dealt with at the Old Bailey in the Sessions of Gaol Delivery or at the Court of the King’s Bench in Westminster (from https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/london-metropolitan-archives/visitor-information/Documents/39-a-brief-guide-to-the-middlesex-sessions-records.pdf). A report in The Times seems to indicate she was tried by magistrates. -Naomi

Hi, I am the 2nd Great Grand Niece of Jane Sarah Mouatt, I am glad to say no harm came to her that day, and she went on to marry and have 5 children of her own,

Thanks for this information – so pleased to hear it!