I was all set to give a talk on 1 May at the National Theatre in London exploring themes in Lucy Kirkwood’s play The Welkin, which was then in performance. Of course, the Coronavirus lockdown meant everything was cancelled, so I am instead posting some of that talk here.

*Although some aspects of the plot of The Welkin are discussed in this post, there are no plot spoilers – but please be aware that there is discussion of public execution, pregnant bodies and abortion, so if you find these themes difficult please stop reading now.*

On 23 December 1930, 37-year-old Olive Kathleen Wise begged to be admitted to her local workhouse in Walthamstow, east London – but she and her four children were turned away. The next day she went to a neighbour with the body of her nine-month-old baby son in her arms. She had gassed him in the oven.

Olive’s trial took place in January at the Old Bailey, where the jury convicted her of murder but recommended her to mercy. Mr Justice Charles agreed. He accepted her defence that she was a devoted mother driven to her terrible act by poverty and desperation. Her dead son had been born out of wedlock after she had been abandoned by her husband. The baby’s father was a widower who had promised marriage but only if he had proof that she was free to marry.

It was obvious during her trial at the Old Bailey that Olive was pregnant and her lawyer requested that a jury of matrons be convened to confirm it. This panel of twelve women concluded that Olive was indeed expecting (she was actually carrying twins) and, after this was confirmed by a doctor, the judge duly granted a stay of execution.1

What were the origins of this arcane legal process in which female members of the public, chosen because they happened to be in court, decided whether a woman was pregnant or not and thereby affected the immediate fate of a condemned woman? And how did it finally come to an end? In this post I look at the long and troubling history of this post-conviction life-or-death plea and at some of the women whose lives depended on it.

Pleading the belly

In The Welkin, which is set in rural Suffolk in 1758, Sally Poppy is found guilty of a gruesome and senseless murder and sentenced to death. She then ‘pleads her belly’, meaning that she claims to be pregnant. A pregnant woman could not be executed as this would effectively be a murder of the baby; the state would have to wait until after she had given birth. There was a high chance, during that interval, that the authorities would commute her capital sentence. If, on the other hand, she was found not to be pregnant and she was not respited for other reasons, the sentence would usually be carried out within 48 hours. (It is as well to remember that about ten per cent of capitally convicted men and women were executed, with the rest being transported, imprisoned, fined, sent into the military or to sea or, occasionally, given a free pardon.)

But how could the court know if the condemned prisoner claiming pregnancy was telling the truth? And who was to say so?

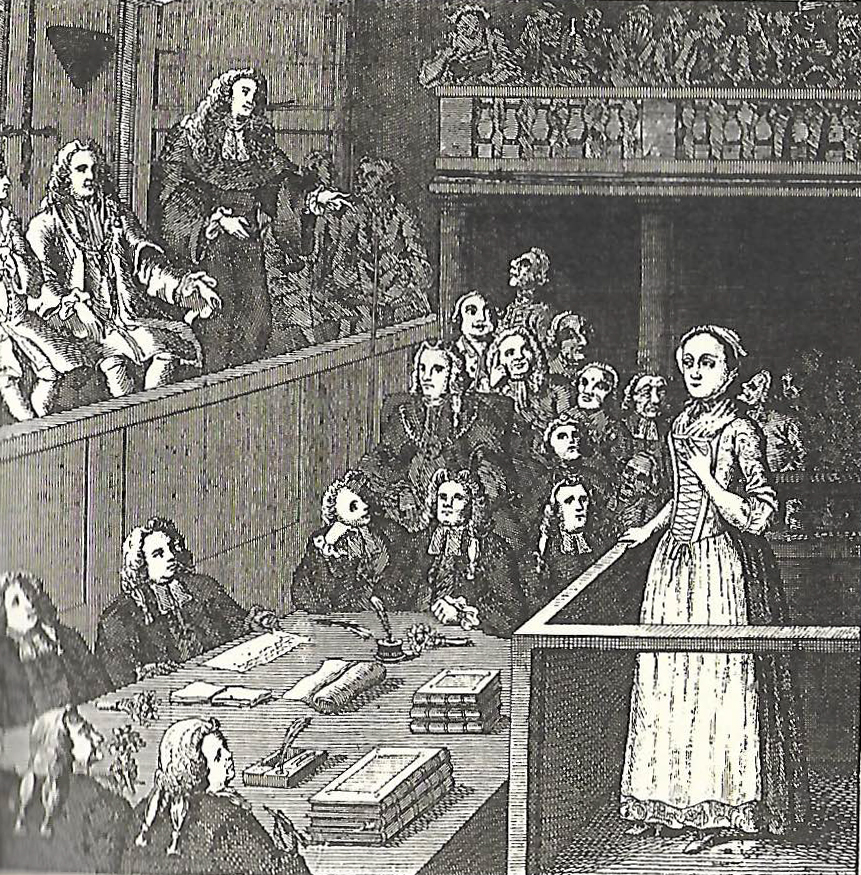

This is where the panel of twelve women, the jury of matrons, came in. Until 1919, when women were permitted on court juries, this was the only decision-making role assigned to women in any legal process. Men, of course, held all the offices of court, from the judge to the lowliest javelin man.

The jury of matrons

Who were the women on a jury of matrons? They were twelve married women with experience of child-bearing who were in court at the time. Typically after a jury of matrons was convened, the under-sheriff of the court identified candidates and they were then called to be empanelled. Sometimes women were reluctant to serve, perhaps because they knew the prisoner and wished not to be involved in her fate, or because they feared her. This is the case in 1809 at the murder trial of Mary Bateman, the so-called Yorkshire Witch. As Mary pleaded her belly the women in the court stood up to leave and Justice Le Blanc had to order the court doors to be locked.2

The forematron was appointed and sworn by the clerk of the court, followed by the other members. There would have been occasions where there were not enough women in the court building, so it is feasible that some jury members might have been passers-by or even women living nearby and fetched by the bailiff. The prisoner and the jury were then taken off to a private locked room. The bailiff was sworn to keep them ‘without meat, drink or fire, candlelight excepted. You will suffer no person but the prisoner to speak to them; neither shall you speak to them yourself, unless it be to ask them if they are agreed on their verdict, without leave of the court.’3

The origins of the jury of matrons lie in a 13th-century property dispute. In 1220 Peter Constable of Melton alleged that Muriel, the widow of his brother William, was falsely claiming to be pregnant by her husband. This was a crucial to his fortunes. A baby would inherit the estate. If there was no baby, Peter was the heir. Muriel went through two examinations by juries of matrons and stuck to her story – until 48 weeks after her last ‘meeting’ with her husband, at which she dropped her claim and admitted that she had never been pregnant. She may have planned to borrow another woman’s baby to act the part of her own but was foiled when the court granted Peter the right to keep her in custody under the watch of four London matrons.

‘Quick with quick child’

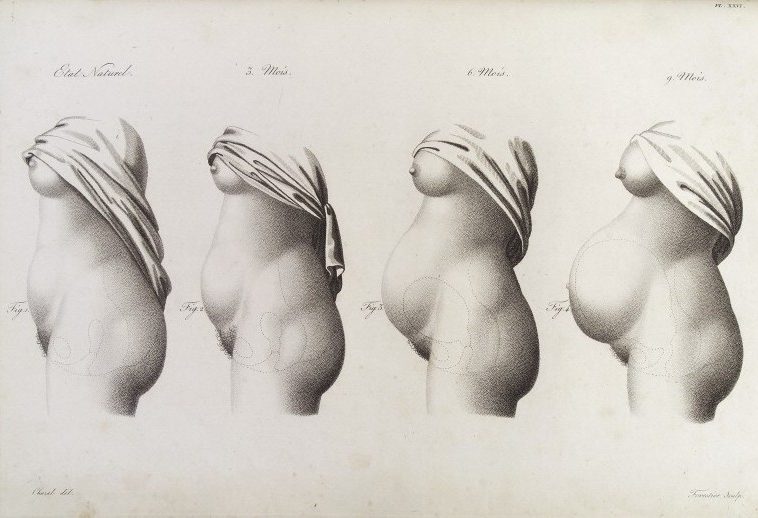

Let’s return to the locked room, in which twelve matrons examine the prisoner for signs of pregnancy. The early signs are sometimes felt by the woman but not apparent to anyone else. Tenderness of the breasts, waves of mild nausea, vivid dreams. But it was not the task of the matrons to assess whether the prisoner was merely pregnant. They had to decide whether she was ‘quick with quick child’.

What does this strange phrase mean? ‘Quick’, which derives from the Germanic, means alive and quick with child means pregnant.4 Quick with quick child means so far gone that the baby has moved in the womb, that it has ‘quickened’, producing a feeling of fluttering or tapping. Women who have already had a baby may experience stronger quickening earlier in their term – sometimes as early as 14 weeks – because the uterine muscles are more relaxed. The distinction between merely quick with child and quick with quick child arose because there was a belief that the foetus received life at the point when it quickened. As the legal commentator William Blackstone said: ‘Life… begins in contemplation of law as soon as an infant is able to stir in the mother’s womb.’ 5

The definition of quick with quick child was also important in prosecutions for abortion, which was a felony crime and thus punishable by death. There was also a little considered anomaly between the ‘law of Nature’ relating to quickening and the law of real property. In the latter, an infant was held to exist from the moment of its conception (as had been the case with Muriel in the 13th century) yet if its mother was found guilty of a hanging crime before her foetus had quickened it would be deemed not to exist and could be executed along with its mother.6

Evading the gallows

If a woman had good reason to believe that she would indeed be hanged, there were some strategies open to her. None guaranteed success.

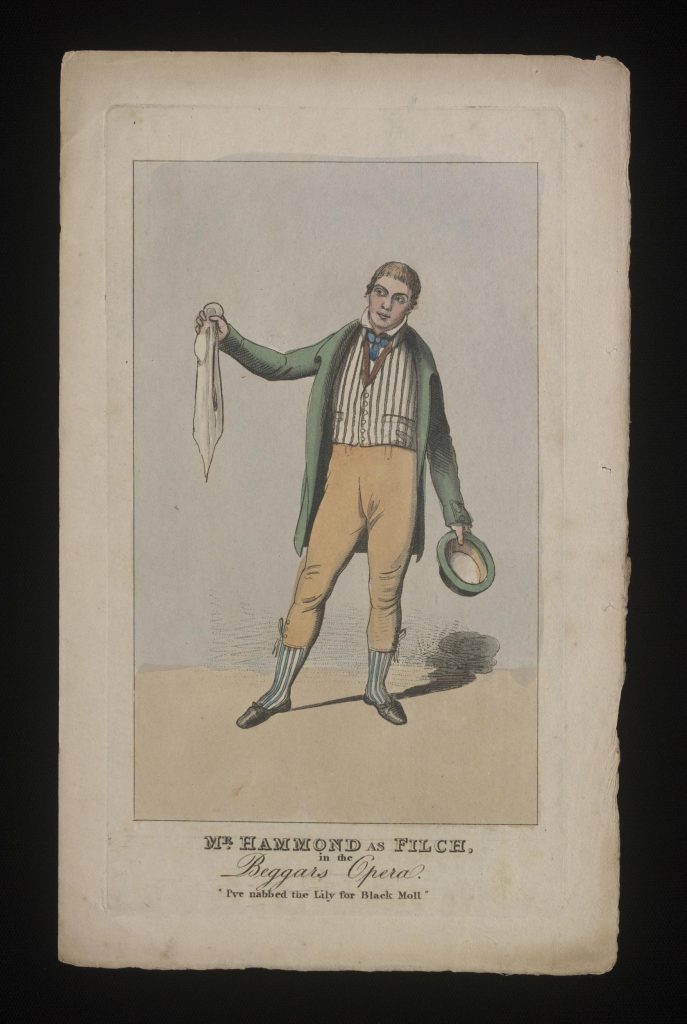

In London, where prisoners could languish for months before being called to court, it was not unknown for women of childbearing age to attempt to get pregnant while behind bars. In The Beggar’s Opera, John Gay’s 1728 portrait of the underbelly of London society, Filch has a notable line about such women. He was paid, he said, to get them pregnant: ‘helping the ladies to a pregnancy against their being called down to sentence.’

Some played for time. In 1814 Justice Hardinge described Sarah Chandler‘s crime – counterfeiting bank notes – as ‘the wickedest forgery ever perpetrated’. He was determined that she should hang, even though she was not part of a counterfeiting gang, was caught early on and had no prior history of criminality. Her scheme was creative and simple, if naïve.

Sarah, a farmer’s wife who lived just outside Presteigne in Radnorshire, was so short of money for food and the children’s shoes that she became desperate and resorted to making her own bank notes, or at least adjustments to real ones, at her kitchen table. She tricked a local printer into printing up the numbers 5 and 2 on sheets of paper and then cut them out and pasted them over the 1 on notes from the local bank. She was soon arrested, tried, found guilty and given a sentence of death.

The Bank Restriction Act of 1797, which for the first time allowed low denomination notes – £1 and £2 – had led to an explosion of counterfeiting. George Hardinge wanted to use Sarah’s execution as an example to others and wrote to the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth to dissuade him from recommending Sarah for the Regent’s mercy: ‘[The] infliction of capital punishment upon Susanna [sic] Chandler is indispensable to public justice and mercy well understood.’

Sarah did not plead her belly at her trial, but soon afterwards her supporters, including directors of the bank whose notes she defaced, petitioned for leniency. When Hardinge received information from Sarah’s friends suggesting that she was pregnant, he suspended the order for her execution, although he suspected that Sarah was lying. Still, he was prepared to wait in order to be absolutely sure and he was aware that there was strong local feeling about her.

Unluckily for Hardinge, the hiatus meant that Sarah, who was not pregnant, did not go to the gallows during the current assizes (he would have to wait until the next session), and that gave her enough time to scale a prison wall and escape, with help from her friends and family, and flee to Birmingham. By the time she was located and hauled back to Presteigne two years later, Hardinge had died and the will to kill her had evaporated. Sarah’s sentence was commuted to transportation to New South Wales.7

The unlucky few

I said earlier that most women had their deferred sentence of death commuted if they were pregnant at the time of their conviction but there were notable, and awful, exceptions to this. In 1757, Margaret Larney, a poor Irish woman, married with five children and living in the Covent Garden area of London, was arrested and charged with degrading the coin of the realm, an act of high treason.

Margaret – and possibly her husband too – earned money by filing off flakes of gold from the flat areas of gold sovereigns and sold them on. At her trial at the Old Bailey Margaret claimed the witnesses were telling lies but that cut no ice and she was found guilty (her husband was not convicted).

Dear Sir / I am the unfortunate woman that now lies under sentence of death in Newgatt I had a child put in here before when I was sent here his name is James Larney and this his name is John Larney and he was born the King’s Coronation Day 1758 and Dear Sir I beg for the tender mercy of God to let them know one and other for Dear Sir I hear you are a very good Gentleman and God Blessing and Name be with you and they for ever / Sir I am you humble / Servant Margaret Larney

James Larney was not at the Foundling Hospital. Two of Margaret’s children were admitted to the workhouse, where they died

Margaret said she was pregnant and the jury of matrons agreed. While she was in Newgate, she gave birth to a son but her pleas for mercy – for transportation – were not supported by Stephen Roe, the Ordinary (chaplain) of Newgate, who said her crimes were too serious to merit it.

Sarah had ‘contravened a law so important and necessary to the preservation of the current coin of the nation entire and undiminished, on which the public credit, commerce, national justice and the facility of dealing do greatly depend.’

Stephen Roe, Ordinary of Newgate, on Margaret Larney

Margaret was a Roman Catholic and Irish, which did not go in her favour, and she refused to admit that she was guilty. The state liked condemned prisoners to be contrite as an example to others and as an affirmation that their death was justified. Margaret was executed by being drawn to the gallows, strangled and burnt, at Tyburn on 2 October 1758.

Larney was certainly unfortunate. Many others guilty of similar crimes were transported or imprisoned. In 1781 Ann Lucas was found guilty at Kingston on Thames for coining silver, pleaded her belly and subsequently gave birth to twin sons. Then she was given a free pardon. The exact reason for her good fortune will never be known.8

By the end of the 18th century, it was only murderers who were left with little hope of mercy after giving birth, and women who killed their husband were always viewed most harshly by the legal system. In 1812 Edith Morrey and her husband George, farmers at Hankelow, just south of Crewe in Cheshire with five children, took on a new labourer, 20-year-old John Lomas. Pretty soon Edith, 37, was having an affair with him. One night they sneaked up on George while he was sleeping and Lomas attacked him with an axe while Edith held the candle. She handed him a razor to finish the job. They were suspected immediately and were both charged with murder. Lomas was executed in August within days of their trial at Chester but Edith pleaded her belly. On 23 April 1813, four months after the birth of her son, she was drawn on a hurdle to the gallows and hanged for murder and petty treason and her body donated to surgeons to be anatomised.9

Doctor in the court

As medical science advanced, so did nervousness over the accuracy of the jury of matrons’ verdicts. By the early 19th century there were reports of surgeons and man-midwives being called in for their opinion.10 In 1804, Ann Hurle was facing death on the gallows for a £500 fraud (she had claimed an old man her aunt worked for had signed shares over to her). When John Silvester the Recorder of London asked her if she had anything to say as to why her sentence should not be carried out, her lawyer, answering on her behalf, said that she believed herself to be pregnant but was not sure. The jury of matrons was not sure either and after they declared that they could not make a decision the sheriffs called in Dr Thynne who found that Ann was not quick with quick child and her execution outside Newgate proceeded.11

In 1833 Mary Wright, from a small village on the coast of Norfolk, was found guilty of murdering her husband by putting arsenic in his plum cakes. In court she pleaded her belly and was examined by a jury of matrons, whose verdict was that Mary was not quick with quick child. Justice Bolland was not convinced and sent for not one surgeon but three because he wanted to be absolutely sure. One of them, Arthur Crosse, disagreed with the matrons and declared that Mary was indeed pregnant. She later gave birth in prison and her sentence was commuted.

A turning-point came in 1838, when the jury of matrons at the murder trial of Anne Wycherley in Stafford themselves requested the assistance of a surgeon. Justice Gurney’s first reaction was to refuse: ‘I think that I ought not, considering the terms of the bailiff’s oath, to allow a surgeon to go to the room in which the jury of matrons is, and that they should come into court.’ Eventually, Gurney agreed that Mr Greatorex, a surgeon and accoucheur (man-midwife) who happened to be married to the forematron and was a witness in another case, could give evidence. He examined Ann and took the stand to say that he was of the opinion that Wycherley was not pregnant or, if she was, only in the early stages.

‘”Quick with child” is having conceived. “With quick child” is when the child has quickened. Do you understand?’ asked Gurney.

‘I do, my Lord,’ replied Greatorex.

The jury of matrons then retired and found that Wycherley was not pregnant.12 Even then, the law was reluctant to proceed and Wycherley’s sentence was stayed, but only for a few months: she was executed on 5 May outside the county gaol at Stafford.13

Doctors expressed horror at the thought that a mistake might be made in such cases. In 1843 the British Medical Association passed a resolution condemning the law that allowed a distinction between quick with child and quick with quick child and four years later there was a stark example of the need for caution. A jury of matrons, who had earlier been offered the services of a surgeon and declined it, declared Mary Ann Hunt, who had been found guilty of murder, was not pregnant. The Home Secretary ordered an examination by doctors who decided she was. She gave birth three months later to a premature son.

The end of the jury of matrons

Pleading the belly continued but its occurrence in court was so rare – because by now the number of crimes that attracted the death penalty was reduced, effectively, to murder or attempted murder – that people were astonished when it cropped up. Even allowing for the journalist’s misogyny and dramatic licence, accounts of the 1872 Old Bailey trial of Christiana Edmunds, the so-called Chocolate Cream murderess, were shocking. Sentence was passed on Edmunds, during which the judge struggled to contain his emotion, and the Clerk of Arraigns asked her whether she was pregnant. The reporter for The Globe, described the awful scene:

‘The prisoner… whispered to the female warder, who again whispered to the jailer, who said aloud, “She says she is, my lord.” There was a profound sensation among the bystanders at the unexpected announcement which was not diminished when the words, “Let the Sheriff empanel a jury of matrons forthwith,” were heard… After about twenty minutes a dozen well-to-do and respectably-dressed women – who could have supposed that a dozen such were to be found in such a place? – were captured and directed to enter the jury-box, into which they marched and took their seats as if it was a matter of everyday occurrence. Mrs Adelaide Whittaw, the forewoman was sworn separately, and then the rest in a body. It was arranged that they should see the prisoner in the Sheriff’s parlour. Half an hour elapsed. when a messenger came into Court, and an inquiry was made aloud by the Judge whether there was an accoucheur in Court. Presently a doctor was found, and directed to join the matrons. Half an hour more of suspense and eager interest. A messenger again comes in and whispers, and the rumour goes about that the doctor requires a stethoscope. There is a touch of comedy even in the midst of the tragic scene, for they say that a policeman has been sent to fetch one, but has brought back a telescope instead. More delay, more suspense. Here they are at last. The prisoner again at the bar, the matrons again in the box. The verdict is spoken by the forewoman in a single word “Not.”

‘The humanity of the rule of law which leaves this delicate matter to the decision of twelve women accidentally present in court during a murder trial…is…very questionable, and the result has on more than one occasion proved to be very fallible. The sort of women who care to be present at such scenes are not presumably the most intelligent or best educated of the community, and the question which they have to investigate might in modern days of medical science be answered far more satisfactorily by a medical man. Besides, the question itself is somewhat difficult, even for medical men to answer, and one about which there has been much professional disputation in modern times.’

The Globe‘s writer recalled the near-misses in the pregnancy verdicts on Mary Wright in 1832 and on Mary Ann Hunt in 1847 and expressed the hope that the matrons would soon be replaced with ‘proper scientific investigation’.14

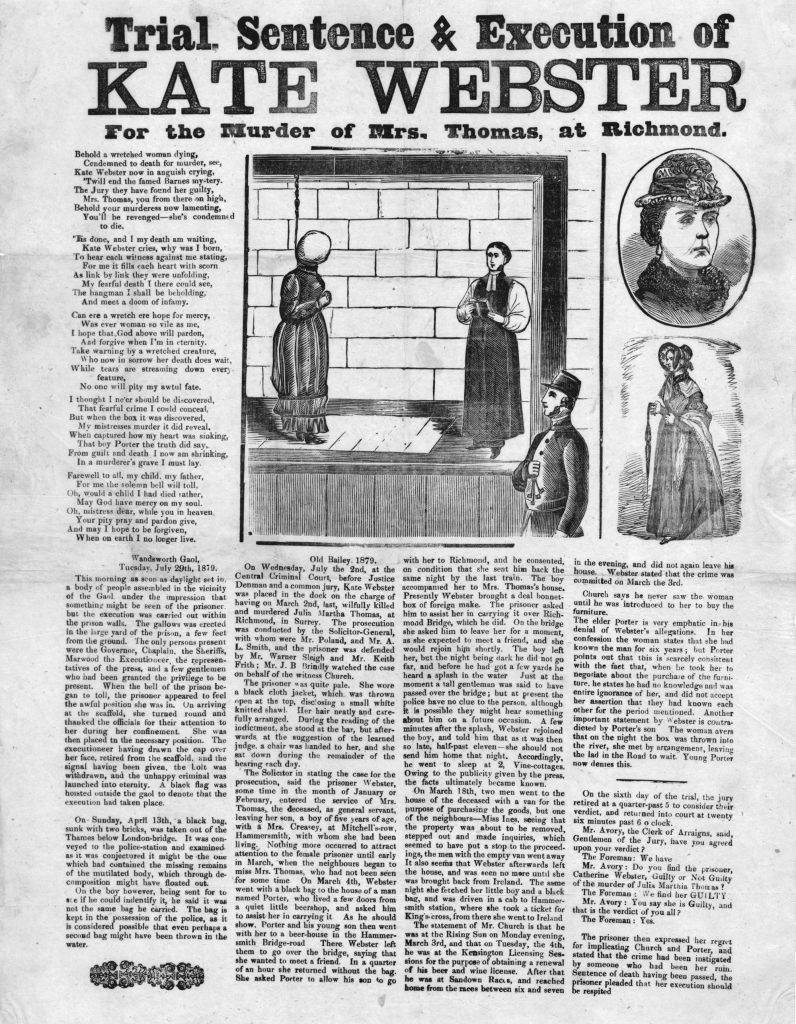

When Kate Webster, who committed a particularly grisly murder, made her plea for a stay of execution in 1879, the judge, Mr Justice Denman, observed that this was his first experience of the kind in 32 years on the bench.15 The Lancet was incensed by the process. ‘The whole episode of “a jury of matrons” is a farce which justice, indecorously and at an unseemly time, performs for the gratification of archæological tastes.’16

Further cases sporadically troubled the media, serving only to provide evidence of the pointlessness of convening a jury of matrons when doctors would also give evidence and of subjecting pregnant women to a death sentence only to commute it later. Carrie Thomas, a destitute servant who had been in and out of the workhouse, was condemned at Bodmin in 1906 for drowning her illegitimate child (she said she had intended to drown herself too but could not manage it) and respited by the judge, but within days had given birth to a premature child died who died. At the inquest for the baby, the medical officer of Bodmin prison told a coroner’s court that Carrie Thomas had not been fit to stand trial.17 There was also a growing understanding of how women’s difficult lives affected their mental health. In 1913 26-year-old married nurse Ada Annie Williams was convicted of the murder of her illegitimate four-year-old disabled son. Her husband, with whom she had two further children, had constantly taunted her about him, deserted her and failed to pay adequate maintenance.18 She gave birth to a boy in Holloway Prison and was discharged on licence in 1921. In 1917, 25-year-old munitions worker Ethel Stevens was convicted of drowning her baby son at Stanwell and sentenced to death but claimed pregnancy and was respited.

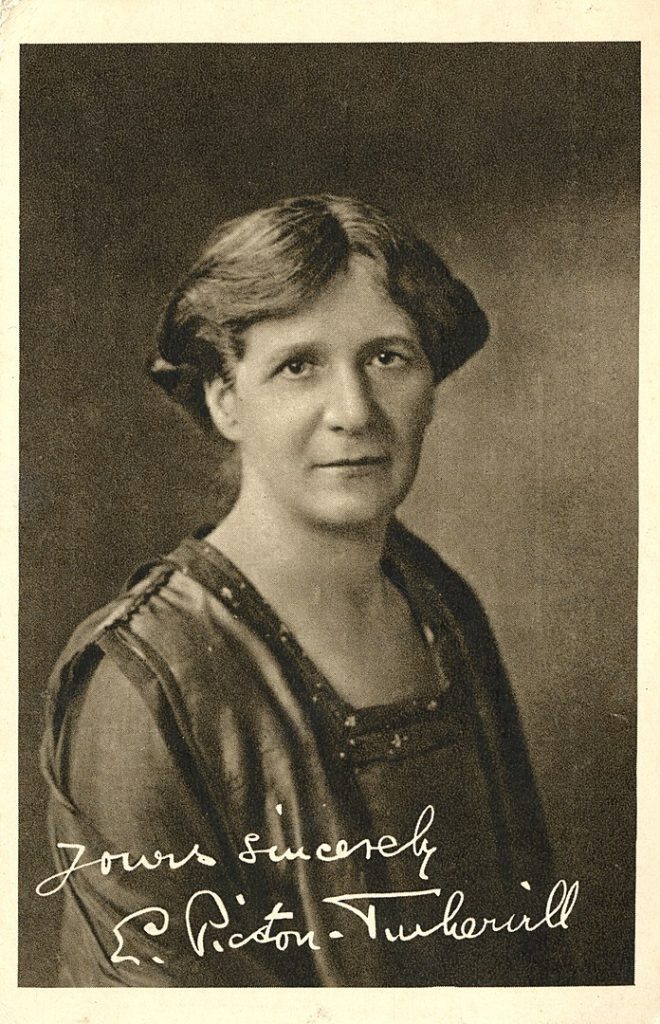

Change came with Olive Wise’s trial in January 1931. Later that year the jury of matrons was abolished after Parliament passed the Sentence of Death (Expectant Mothers) Act, presented by Labour MP Edith Picton-Turbervill. The legislation also said women who are capitally convicted while pregnant must have their sentences commuted.

What happened to Olive? She was released from prison in July 1932, having served 17 months of her sentence, an apt illustration of the injustice of her original sentence. She married the father of her twins and the boy she killed. 19

Although the jury of matrons has gone, in countries where capital punishment still exists pleading the belly has not. In 2016 in Vietnam Nguyen Thi Hue, 42, who had been convicted of drug offences and sentenced to die, arranged for a male prisoner to smuggle his sperm to her. Her subsequent pregnancy protected her from the firing squad and her sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

- Dundee Courier, 17 Jan 1931, 4E.

- Anon. (1811). Extraordinary Life and Character of Mary Bateman, the Yorkshire Witch. Leeds: Davies and Co, Stanhope Press. Bateman was found not to be pregnant and was executed at York on 20 March 1809. Mary’s body was dissected by Dr William Hey at Leeds General Infirmary and it was confirmed that she was not pregnant.

- The Legal Observer, Or, Journal of Jurisprudence (1836 May-Oct), Vol. 16, p. 206. The account relates to the 1838 trial of Anne Wycherley for murdering a three-year-old child (Reg. v. Wycherley, 8C. & P. 262). Anne was judged not to be pregnant and was executed at Stafford on 5 May 1838.

- It was applied to the description of the foetus in the Anglo-Saxon Metrical Charm 6: Charms for Successful Pregnancy (“For Delayed Birth”): Up ic gonge, ofer þe stæppe mid cwican cilde, nalæs mid cwellendum, mid fulborenum, nalæs mid fægan.

- William Blackstone (1765), Commentaries, Amendment IX, 1:120–41.

- John Ayrton Paris, John Samuel Martin Fonblanque (1823). Medical Jurisprudence, Vol 3, p141.

- HO 47/53/20.

- Kentish Gazette, 8 Aug 1781, 4A.

- Anon. (1812). Trial & execution of John Lomas, and condemnation of Edith Morrey, for wilful murder (broadside).

- If you know of earlier examples, please contact me.

- Kentish Gazette, 24 Jan 1804 2D; Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 12 Feb 1804, 7A. Ann Hurle was hanged on 8 February 1804.

- Frederick Augustus Carrington, Joseph Payne (1839). Reports of Cases Argued and Ruled at Nisi Prius, in the Courts of King’s Bench & Common Pleas, and on the Circuit: from the Sittings in Michaelmas Term, 1823, to [Easter Term, 4 Vict. 1841], Vol 8, p. 262. London and Dublin: S. Sweet & R. Milliken and Son.

- Staffordshire Advertiser, 12 May 1838, 3B.

- Globe, 17 Jan 1872, 8C.

- Cited in Thomas Forbes (1988), ‘A Jury of Matrons’. Medical History, No. 32, pp. 23-33.

- Quoted in New York Times, 4 Aug 1879.

- Cornishman, 28 June 1906, 5B; Royal Cornwall Gazette, 12 July 1906, 6F.

- The Suffragette, 19 Dec 1913, 3C.

- Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 5 Sep 1932, 8B.

Hi Naomi,

Olive Wise was my grandmother & a few years ago I acquired the court papers including some distressing evidence of how awful things were in those times. My father was one of the 4 boys who were taken into Dr Barnados & the twins were also raised there. The twins are still alive & well!

Many of her descendants went on to have professional careers, all helped by the security & guidance from Barnados.

Olive had other children before & after & some accounts say she had 13 in total.

I’m delighted that she has been mentioned in your work

Many Thanks

Candy