On the morning of 10 November 1801, shortly after breakfast, Mary Voce, a young married woman ‘in the prime of life and comeliness of person’ living apart from her husband in Fisher Gate in Nottingham, mixed arsenic with water in a teacup and carefully poured it into the mouth of her six-week-old baby. The reaction was instant. The baby screamed in agony, distressed beyond description. Mary, despite being the agent of her daughter’s pain, was heart-broken, shocked and frightened, and paced back and forth, wringing her hands and wailing. Neighbours soon came to help and console her, but within a couple of hours it was all over. The baby was dead.

After the inevitable inquest Mary was taken up and committed for trial at the next Nottingham assizes, to answer charges of murder. In prison she was regularly visited by Methodist preachers, including John Clarke, Miss Richards and Elizabeth Tomlinson, who prayed with her and tried to get her to accept her guilt. Mary, however, resolutely stuck to her assertion that she was innocent.

She admitted that she had not led a blameless life, and latterly, after trying to find work batting (carding) cotton, had turned to ‘other methods which it is too painful to relate’ (sex work). She had also been unfaithful in her marriage to Thomas Voce, a military pensioner. Voce was required to travel to Chatham, a distance of over 160 miles, in order to confirm his entitlement and it was during one of these extended absences that she had taken up a lover, not her first, and become pregnant with Elizabeth.

There was only one surviving child from the marriage, a boy of five, but Thomas Voce suspected he was not actually the father. His resentment spilled over into violence and the couple had frequently separated. Mary’s latest lover had abandoned her and she had begged Thomas to accept her back, which he did for a while, until he left her again, penniless and with a new baby to support.

Life had always been hard for Mary. She had been born Mary Hallam in 1778 in Sneinton, not far from Nottingham. Her parents, who had not married, died early and her care had fallen to her relatives. She had seen her marriage to Thomas Voce as a path to stability but it had been a disaster. She was destitute and desperate.

Mary told her prison visitors that she had obtained the arsenic intending to kill herself and not the baby. She had asked a friend, William Jackson, to accompany her to witness the purchase and to confirm that she needed it to poison rats. At home, she had put it in a teacup on the hob but on the morning of the tragedy a neighbour had asked her to breakfast. She left the baby in her lodgings and while she was gone a child must have slipped in and mistakenly thought to do the baby a service by giving her water, little realising that the cup contained poison.

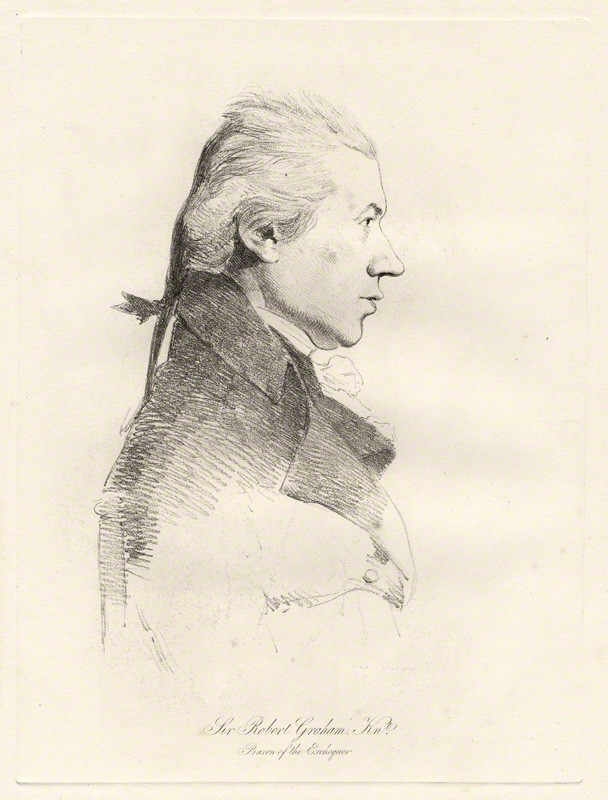

On 12 March 1802 Mary Voce appeared before Sir Robert Graham at the Nottingham Lent Assizes. This urbane and admired judge was known for his humanity and his ‘religious, moral and social qualities’.1 In the absence of defence counsel the judge’s role was to act in the interests of the accused felon.2

When Graham asked Mary if she had anything to say she handed him a piece of paper. It refuted the charge and blamed the neighbourhood children. She repeated the explanation that she had been absent from the lodgings, and a child must have taken the poison from the hob and given it to the baby just as she returned. She claimed that she had bought the arsenic intending to poison herself and that Thomas Voce had been abusive to her. Graham gave her assertion careful consideration and a witness was called who confirmed that Mary had indeed been asked to breakfast that morning. He accepted that she may have been abused by her husband but ‘motive and cause for such treatment, was, alas!, too apparent’, that is, Mary’s infidelity had given him justification. However, humane Graham was, it is not extend to an understanding of the corrosive effect of domestic abuse.

In summing up the case, Graham ‘took particular notice of every circumstance which had appears in her [Mary’s] favor’ and ‘called the attention of the jury to her apparent state of mind during the illness of her infant’ (wringing her hands and weeping was, he said, a genuine display of grief), but Mary was not insane and there were so special grounds for a plea for mercy.

The jury deliberated for 10 minutes and declared her guilty. During the sentencing, ‘His Lordship and the whole court were deeply affected’. Mary herself was scarcely able to stand and announced that she wanted to die. She was removed from the bar and taken to Nottingham Gaol to await execution. Someone was with her at all times to prevent her suicide.

In the condemned cell, Mary continued to deny her guilt, until finally persuaded by her Methodist visitors that confession would lighten her soul. At 2pm on Saturday she cried out, ‘Oh my heart will break! My heart will break!’ She sent a message to her husband to say she did not want to see him again but hoped that he would forgive her. She had a final meeting with her young son.

By Sunday she was ‘quite comfortable and resigned’. The next day, 16 March 1802, at 10am the under sheriff and his constables arrived to take her to Nottingham’s Gallows Hill.3 She took her leave of the governor, Mr Bonington, and his maid and other female prisoners. Then she was placed, seated backwards, in the cart, her Methodist advisers and her empty coffin accompanying her. She told them: ‘This is the best day I ever saw. I am quite happy. I had rather die than live’ and ‘I am so happy I cannot cry. I cannot shed one tear.’ When they got there, Miss Richards said: ‘We are got there, Mary.’ She replied, ‘Well bless the Lord.’

She greeted the executioner with a smile and gave him her hand. ‘Bless you, I have nothing against you. Somebody must do it,’ she said and assisted him in placing the ropes. As the cap was put over her head, she exclaimed, ‘Glory! Glory to Jesus! I shall soon be in Glory. Glory is indeed already begun in my soul, and the angels of God are about me!’ She dropped and her body was left to hang for an hour, and then handed to surgeons for dissection. Her remains were publicly displayed.

Two years later, Elizabeth Tomlinson, ‘a small black-eyed woman’ known for her ‘vehement’ preaching style, married Samuel Evans at around the same time that the Methodist church ceased to allow women to be ministers. Elizabeth went on to have three children and was also a beloved and devoted aunt. Her niece Mary Ann, the daughter of Samuel’s older brother Robert, was particularly fond of her, and listened attentively to her recollections. When Mary Ann was 20, her Aunt Elizabeth told her about sitting with Mary Voce before her trial and in the condemned cell and the efforts she and her companions had made to bring her to confess.

Twenty years after that, Mary Ann Evans, using her pen name George Eliot, published Adam Bede, the story of the beautiful by morally vacant Hetty Sorrel, her seducer Captain Arthur Donnithorne and Adam Bede, her unacknowledged suitor. It was not based accurately on Mary Voce’s story but it includes many of the elements related by Elizabeth Tomlinson.

The germ of “Adam Bede” was an anecdote told me by my Methodist Aunt Samuel … [Elizabeth Tomlinson]: an anecdote from her own experience. We were sitting together one afternoon … probably in 1839 or 40, when it occurred to her to tell me how she had visited a condemned criminal, a very ignorant girl who had murdered her child and refused to confess – how she had stayed with her, praying, through the night and how the poor creature at last broke out into tears and confessed her crime. My Aunt afterwards went with her in the cart to the place of execution, and she described to me the great respect with which this ministry of hers was regarded by the official people about the gaol.4

Sources: The first three broadsides are reproduced as Appendix 2 in the Oxford World Classics edition of George Eliot’s Adam Bede. Henry Taft, An Account of the Experience and Happy Death of Mary Voce, who was executed on Nottingham Gallows on Tuesday, 16 March, for the Murder of her Own Child. C. Sutton; The Life, Character, Behaviour at the Place of Execution and Dying Speech of Mary Voce. Burbage and Stretton; A Full and Particular Account of the Life, Trial and Behaviour of Mary Voce. Sutton; The last dying words and confession of Mary Vice [sic]: who were executed on Nottingham Gallows, on Tuesday the 17th day of March, for the willful murder of her child by poison. Leicester: Pares, printer, High-street [1802].

7 years late to the party, I wonder what became of her son Thomas Voce Jr who was born in sept 1793 just one month after Mary & Thomas married in Aug 1793. He was lucky to survive.

It’s so difficult to be sure, Deborah. I have found two men named Thomas Voce in Nottinghamshire, born around 1793. One was working as an ag lab in Clipstone in the 1851 census, another, a shopkeeper in Bingham, died in 1848. Could be neither of those, of course…