The second in a series looking at the three women hanged in England in 1836.

BETTY ROWLAND

Hanged at Liverpool on 9 April 1836, for the poisoning murder of her husband William. Aged 46.

Dr. Syntax Attends the Execution, by Thomas Rowlandson (1820). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

William Rowland, a 50-year-old weaver, who lived with his wife Betty in a cellar in Butler Street, Oldham Road, Manchester was taken ill on 18 December 1835 and died the next day. No doctor attended him. Betty Rowland set about arranging his funeral, which was to take place on 22 December, with a burial at Mr Schofield’s Chapel Yard in Every Street.

In the meantime, Jeremiah Cawley, a neighbour who suspected foul play, had a word in the ear of the local beadle, James Sawley, who made it his business to look in at the cellar on the afternoon of the funeral.

There he encountered a lot of drunk guests who did not appreciate his efforts to halt the funeral in order to allow the coroner to view William’s corpse. Betty was indignant and insisted that her husband would be buried. Sawley attempted to arrest her, at which a ‘tall, stout man’ jumped up, and it was only by promising the company that he merely wanted to ask her a few questions that they let him take her.

Samuel Bowstead, Parish Beadle by an unknown artist (1846). © Fulham Palace Art Collection

As they walked to Shudehill lockups Betty said:

‘Oh dear. I never gave him anything but a drop of brandy, and that I borrowed money to pay for. I am as innocent as a child, whether I suffer for it or not.’

And later she said:

‘Oh yes, I gave him three pennyworth of whiskey on Tuesday afternoon.’

The coroner and the deputy constable were informed but as there was no evidence against Betty, she was released. William was buried, but within days he was dug up again because Sawley had made more inquiries. Betty, meanwhile, decided to leave the neighbourhood. William’s stomach was sent for analysis by Mr Ollier, a surgeon, whose tests for arsenic were positive.

At a coroner’s inquest on 30 December Ann Eaton, a neighbouring cellar dweller, told the court that she found William’s body upright in a chair and helped Betty lay it out. Betty had produced a jug from a cupboard and said he’d had a gill of beer and a pennyworth of rum from it before he died. Ann said the Rowlands quarrelled frequently.

Another neighbour, Francis Rochford, said that the deceased was very low spirited and that the Rowlands seem to have recently separated but had been reconciled.

At this stage there was no evidence that Betty had poisoned her husband, only that he had been poisoned by someone. The inquest was adjourned while a search was made for Betty. During this interval, it became known that Betty had bought arsenic from Mr Goodman, a chemist in Oldham Road. Soon after, she was apprehended in Mark Lane by William Booth, the beadle of Chorlton-upon-Medlock, who accused her of poisoning her husband. She denied it and then began to cry, saying, ‘I am guilty, and I don’t care how soon I die.’ She told Booth that she had taken her cousin Alice Tinker to buy a pennyworth of arsenic, saying it was to poison rats. The poisoning had been an accident: ‘I put it into his gruel and thought it was sugar,’ she said. She had failed to call a doctor because she did not think William would die.

Jeremiah Cawley told the magistrate’s court that he had called at the house after William died, and there accused Betty, who was drunk, of murder. He clearly knew a lot about her. ‘How have you disposed of this man?’ he said. She did not reply and he added, ‘You have disposed of him as you did of your other husbands [she had been married twice before]. You have poisoned him, and it is the common report of the neighbourhood.’ He took his suspicions to the police.

Betty claimed throughout that the poisoning was accidental. In the gloom of the cellar she had mistaken the arsenic for sugar and mixed it in the gruel. When she realised what she had done, she threw the remainder into the fire. She also claimed that her husband was violent from the beginning of their three-year marriage.

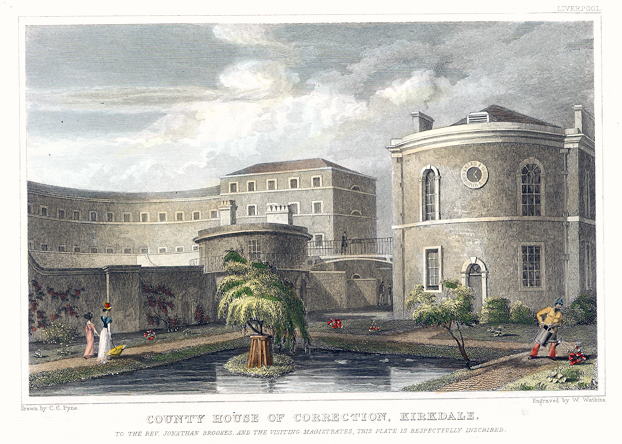

Betty was committed to Kirkdale for trial at the next assizes. Newspaper reports described her as ‘a woman of low stature and very forbidding appearance’.

County House of Correction, Kirkdale (Liverpool) engraved by W. Watkins after a picture by C.Pyne, published in Lancashire Illustrated, 1831. Image courtesy of Ancestry Images.

She was found guilty at the trial on 30 March and sentenced to death. Her execution, in front of the House of Correction at Kirkdale, was a riotous scene. To get a good view spectators started arriving from five in the morning, although the event was not due to go ahead until three in the afternoon. They became bored and started pelting each other with missiles. Police attended but after they left gangs of thieves started stealing tippets, bonnets and shawls from the women, who were forced to take refuge in the gaol and to escape through the court house.

At two thirty the under sheriff arrive, delivered the warrant and Betty,’the unhappy culprit’, was led out to the press room, attended by the chaplain, the Reverend Mr Horner. Wearing a “Lancashire bedgown, a linsey-wolsey petticoat and a frilled cap”, and with her arms were pinioned and her clothes wrapped around her, she emerged from the building. She stood without assistance on the platform and after a portion of the burial service was read, the signal was given, the bolt was withdrawn, and she dropped.1

See also

Leave a Reply