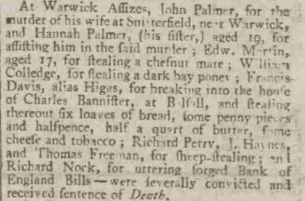

In 1688, the Bloody Code, the term used to encompass all the offences for which the standard sentence was death, included only 50 crimes. By 1765, this had grown to about 165 and in 1815 to 225. Its absurdities are well known and well illustrated in this clip from the Northampton Mercury, which reported in 1801 that, among others, Francis Davis (aka Higgs) broke into Charles Bannister’s house and stole bread, butter, cheese and tobacco, Edward Martin, aged 17, stole a horse, and John Palmer and his sister Hannah committed murder. All of them were told in court they would die within days.

It is also well known that many sentenced to death were reprieved. This was not often the result of simple compassion on the part of the judiciary. It was more likely because society would not have tolerated the judicial deaths of so many people – especially for such comparatively minor infractions. In fact, of those listed by the Northampton Mercury, the horse thief Edward Martin survived (he does not appear in Capital Punishment UK‘s well researched lists of the executed) as did the sheep-stealers Perry, Haynes and Freeman. The other horse thief William Colledge was reprieved but he was hauled up at Worcester Assizes two years later for stealing a mare at Abberley in Worcestershire and died on the gallows.1

The counterfeiter Richard Nock was executed at Warwick on 17 April. Twenty-one-year-old Francis Davis, who took the food, was transported to Australia on the Captivity.2

John Palmer (aged 26) and his sister (a mere 19) can have entertained no hope of a respite after their convictions for murder. While awaiting their fate in Warwick Gaol, they did not bother to express “true contrition” as was expected of the condemned but instead displayed a “studied sullenness, or unfeeling stupidity”.3

For us the word “stupidity” might sound apposite as their crime bears the hallmarks of poor judgement, if not low intelligence. But here, I think it means that they were stunned into silence.

The Palmers were from Snitterfield4 near Stratford upon Avon in Warwickshire. John was a day labourer, married to Mary. They had a child together but the marriage was unstable and the couple separated more than once. At harvest time in 1800, after an absence, John returned to his wife, in order to live off her gleanings from the cornfield. This speaks of a desperate, hand-to-mouth existence, to say the least. What prompted him and his sister Hannah, actively encouraged by his mother Sarah to decide to murder Mary is not known. They tried several times to poison her, but in the end, on 17 November, they enacted a plan to entice her to a field under the pretence of gathering turnips and there to attack her.

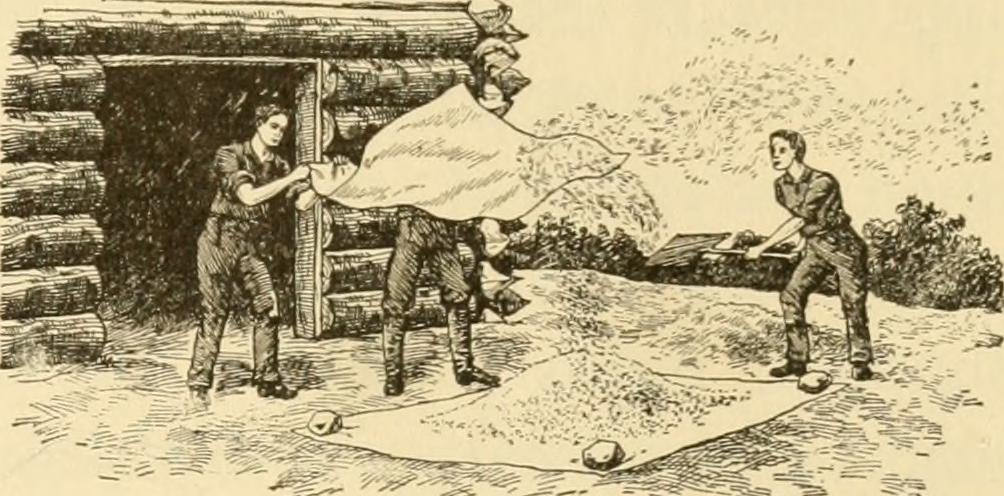

According to the broadsheet published after their execution, the murder was gruesome. While Hannah held Mary’s arms, John slit her throat and to stem the deluge of blood skewered the wound together. After this they sewed the body into a winnowing sheet and threw it into the River Avon, hoping that the waters, which were in flood, would take it far away.

Palmer propagated a story that his wife had gone off with another man, but he had managed to retrieve her clothes (as her husband, these were his property). These he sold to another sister for 2s and 6d, assuring her that Mary would not be returning to reclaim them. How he explained the bloodstains is not known.

Mary’s body was discovered the next day at the weir-break at Welford. Mary’s brother, suspicions raised, managed to obtain some of the bloody clothes. John was soon arrested and carted off to Warwick Gaol and Hannah and her mother followed ten days later.5 Sarah died in prison before she could be tried and her disgusted neighbours demolished her house in Snitterfield.

The siblings were tried at Warwick Assizes. John said he “had no malice in his heart” against his wife and blamed his mother who “would let him have no peace until he had got shut of her.”6 It was reported that he and his sister behaved with great propriety when they were executed together outside the gate of the jail on 1 April. John Palmer’s body was hung in chains near Binton Bridge and Hannah’s body was given for dissection.

The Bloody Code did not give the Palmers pause for thought, as nobody ever plans a death thinking that they will be caught and hanged. At the time, it must have seemed a sensible and safe course of action. John and Hannah had clearly discussed what they would do and assessed their chances of getting away undetected.

The Bloody Code did nothing to deter Francis Davis (alias Higgs), the thief of bread and cheese, who was perhaps motivated by a need that could not be denied: hunger. The only wonder is that, when the penalties appeared to be the same for murder as for theft, more people were not murdered in the course of lesser crimes.

- Oxford Journal, 12 March 1803.

- Home Office: Convict Prison Hulks: Registers and Letter Books; Class: HO9; Piece: 8.

- Last dying speech and confession of John and Hannah Palmer: who were executed at Warwick, on Wednesday the 1st day of April, 1801 for the cruel and barbarous murder of Mary the wife of the said John Palmer. Leicester : J. Throsby, Jun printer.

- William Shakespeare’s grandfather had a house there.

- Nicholas Fogg, Stratford-upon-Avon: The Biography. Amberley Publishing (2014).

- Staffordshire Advertiser, 11 April 1801.

Leave a Reply