After researching so many women who were sent to the gallows,1 sometimes for non-violent crimes or for murders that arisen out of years of abuse, it was heartening to read this story about Mary Ann Adlam who stabbed her husband during an altercation at their premises in Bath Street, Bath, in 1814.

Sarah Ellis did not see the knife in her mistress’s hand, but when her master called her over, saying ‘Sarah, she has cut my coat.’

‘Yes, Mr Adlam, she has cut your coat,’ she replied.

He stretched out his arm and it was only then that she saw it was not just Mr Adlam’s coat that was cut.

‘Oh, Mr Adlam, there is blood!’

Mrs Adlam, who had fled the room after she stabbed her husband, now returned and tried to persuade him to go downstairs where she could tend to him, out of sight of any customers who might visit the shop. Eventually, he consented and she helped him down to the kitchen but he was in such a bad way that he lost his balance and together they fell down almost the entire flight of stairs onto the flagstones.

Mrs Adlam got him into a chair, and he began to lose consciousness. Sarah fetched a surgeon.

The Adlams lived on the premises of their straw hat shop in Bath Street, Bath. cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Graeme Smith – geograph.org.uk/p/718126

Elizabeth Ann Gardner, a neighbour who had come in to help, witnessed an extraordinary scene: rather than berate his wife for mortally wounding him, Adlam was begging her for forgiveness. ‘Come to me, kiss me, forgive me and make it up,’ he was saying. Elizabeth Ann asked Adlam if he thought his wife had harmed him on purpose. He was adamant that she had not.

It was clear Adlam would not survive and indeed, shortly before eight o’clock that evening, two and a half hours after he was stabbed, he expired.

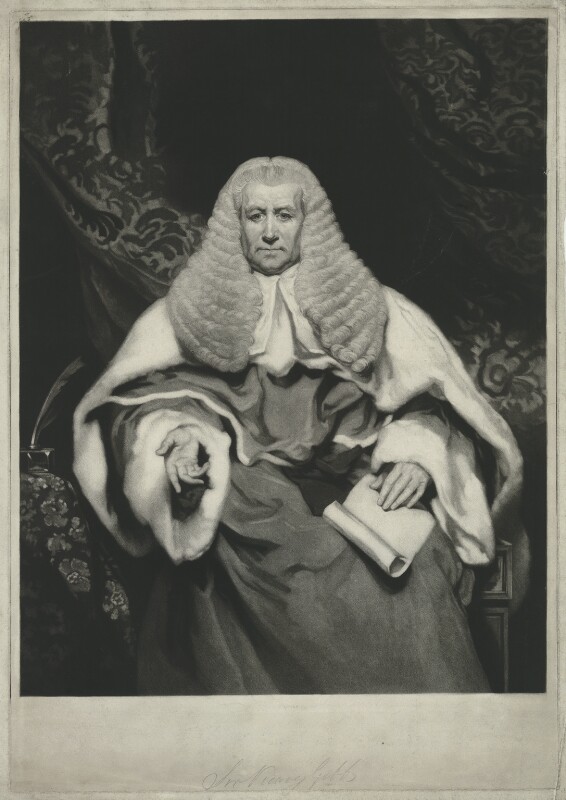

Sir Vicary Gibbs by an unknown artist. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

On 20 August 1814 Mary Ann Adlam appeared at Wells Assizes before Sir Vicary Gibbs2, the famously acerbic judge – he was nicknamed Vinegar Gibbs for his acid tongue. The courtroom was packed.

Mary Ann was charged with murder and petty treason, the latter applicable only to wives for killing their lord and master (that is, for having the effrontery to upend the heaven-ordained hierarchy of society). 3

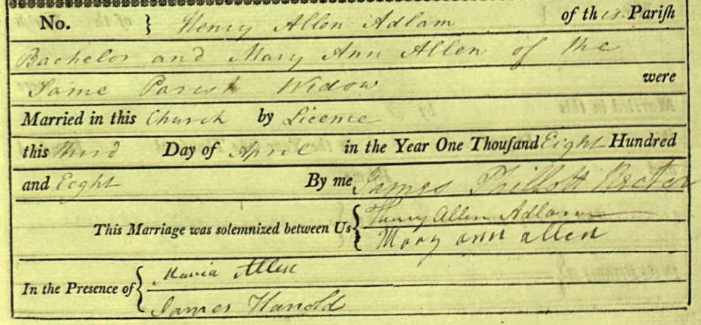

Mary Ann Allen and Henry Adlam were married at St James, Bath on 3 April 1808

Mary Ann Allen, a widow, and Henry Allen Adlam had been married six years 4 but the relationship had turned sour. On the morning of Henry’s death, there was a violent scene between them, during which Henry had banged Mary Ann’s head against a wall. He left the house but when he came back several hours later, he was drunk.

Tea had already been served and the things had been taken off the table. Adlam insisted he should take his tea upstairs rather than in the kitchen, and rang the bell for the kitchen maid. Mary Ann wanted to use the table to line some bonnets and when she said so he struck her to the floor, called her a whore and beat her as she tried to get up.

Then he rushed next door to the shop and stood behind the counter. Mary Ann followed, saying ‘Can you prove me such [a whore]? Why do you live with me and let me support you?’ until Betty the maid dragged her away fearing that Mr Adlam would hit her again.

When Adlam came out from behind the counter towards Mary Ann, she went into the parlour and came back armed with a bread knife from the tea tray.

‘Will you call me that name again?’ she asked.

He did.

In court Sarah, who was now herself behind the counter, swore that she was momentarily distracted at the moment her mistress stabbed her master and did not see it happen – it was only when Mr Adlam said, ‘She has cut my coat’ that she looked up.

Witnesses were called to defend Mary Ann’s character. Mr Southey, a paper stainer of Philip Street, said she was ‘as human, good-hearted a creature as ever was born,’ Elizabeth Ann Gardner, the neighbour who came in to help, said she was ‘very virtuous, humane; a good sort of woman, very affectionate to her husband.’

The jury deliberated for a few minutes and returned a verdict of manslaughter. Mary Ann collapsed. Then Vicary Gibbs pronounced sentence: six months imprisonment. He added that he ‘should not add to her distress by enlarging upon her offence.’

Featured image: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- For my book Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches.

- Recorder of Bristol and Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

- A servant who killed his or her employer or a cleric his ecclesiastical superior could also be charged with petty treason. Petty treason was abolished in 1828.

- I have not been able to trace Mary Ann’s birth name and the fact that Henry’s middle name was Allen suggests that there may have been a family connection between Henry and Mary Ann’s first husband.

Leave a Reply