During the research for my book Unfortunate Wretches one name kept coming up: The Reverend Horace (sometimes Horatio) Salusbury Cotton, the Ordinary (chaplain) of Newgate from 1814 to 1837. There are conflicting opinions of this man. Some described him as “humane”, others saw him as insensitive and slimy with a ghoulish enjoyment of his responsibility for giving convicted felons the news on whether they had been reprieved or would hang.

Horace Salusbury Cotton was born in about 1774, the son of Robert Salusbury Cotton of Reigate. At the age of 17 he matriculated at Wadham College, Oxford, and graduated four years later. By 1800 he was the vicar at Desborough in Northamptonshire1 and by 1805 curate and schoolmaster at Cuckfield Grammar School in West Sussex. By the time he had moved to Hornsey in 1810 he was married to Caroline Amelia Merriman (1803) and had started a family.2

On 29 July 1814 the Court of Aldermen in the City of London appointed Cotton Ordinary (resident Chaplain) of Newgate Prison, replacing the Rev Dr Forde, who had shown such a disinclination to engage with the pastoral responsibilities of his job that he was forced to resign. This was a time of growing disquiet at the appalling suffering produced by the overcrowding, dirt, disease and destitution in Newgate and at the moral degeneration of the inmates. Perhaps the Aldermen felt that the religious fervour of Horace Cotton would improve things.

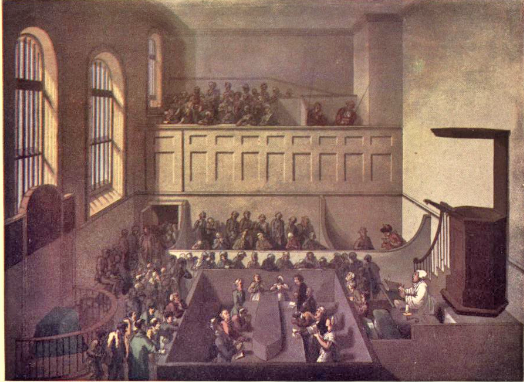

Within nine months of his appointment, Cotton was called to give detailed evidence about his duties as Ordinary of Newgate to the Committee on the King’s Bench, Fleet and Marshalsea Prisons. His answers to the MP Henry Grey Bennet reveal much about his job. He described his routine: visiting the sick, instructing prisoners in their moral duties and administering religious consolation. He gave two services every Sunday and organised a school for boys aged under 15. Tellingly, he felt the prisoners revered him: ‘I always treat them [the prisoners] as reasonable beings; I always take off my hat when I go into the ward, and while I treat them thus, they will treat me with respect.’ Bennet asked him if he kept a journal. ‘No,’ he said. This was a lie. Cotton kept a personal diary, quite apart from his official one, listing all the executed prisoners he encountered in Newgate, and against each name he wrote notes on their crime and their demeanours. Three sketches are included, probably done by a prisoner, each showing Cotton in action in the gaol. The notebook came to light in 2012 during a house sale. The BBC ran a feature on it (video).3

Cotton has been described as a ‘fire and brimstone’ preacher4 and certainly his treatment of the condemned could not be described as in any way ‘nuanced’. He preferred a sledgehammer approach. In his Hangmen of England Horace Bleackley describes Cotton as a ‘robust, rosy, well-fed, unctuous individual, whose … condemned sermons were more terrific than any of his predecessors’.5

Eliza Fenning, a young cook-maid condemned to death in 1815 for the attempted murder of her employer and his family, was deeply distressed by Cotton’s address during the condemned sermon. A friend of her alleged victims, Cotton had chosen Romans 6: ‘What fruit had ye then in those things whereof ye are now ashamed? For the end of those things is death.’ He alluded directly to her, saying that she had been persuaded by Satan that revenge was sweet and that he would protect her, but had then abandoned her. Fenning was almost certainly innocent.

Cotton’s treatment in 1824 of the banker Henry Fauntleroy, who was convicted of a monumental financial deception, attracted more serious censure. He felt it appropriate to take his text from Corinthians: ‘Let him that thinketh that he standeth take heed lest he fall.’ Perhaps he did not see the irony of the text for a man about to endure the New Drop within hours. After Fauntleroy’s death, the Aldermen decided that the public were no longer to be admitted to the condemned service6 and reminded Cotton that his job was to console convicted felons, not to harass or distress them in their remaining time on earth.

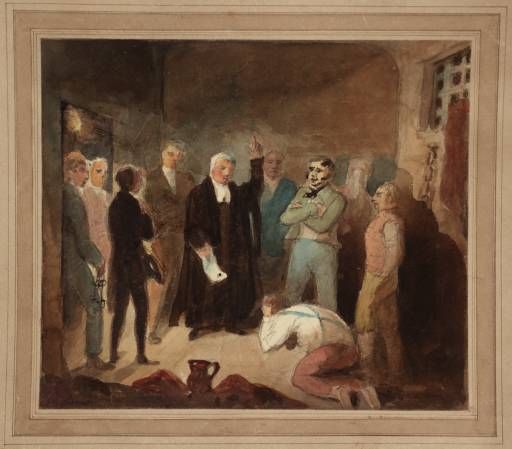

Cotton took a callous, almost sadistic relish in his role with condemned prisoners. The prisoner artist W. Thomson’s portrayal of him announcing the Report (the death warrant) to a convicted felon, standing fully upright, his hand raised, conveys this. This coldness is also seen in the terse conclusions about executed prisoners he recorded in his secret execution diary. Of John Ashton, convicted of highway robbery in 1814, he wrote: ‘This man sprung up on the scaffold after he was turned off [dropped] and distinctly cried out “Am I not Lord Wellington”! He was pushed off again by the Executioner.’

There were rumours that Cotton was venal. The Freethinkers (atheists) who were imprisoned for blasphemy in Newgate were his implacable enemies and in the pages of their journal, The Newgate Monthly Magazine, alleged that Cotton intervened directly in justice. According to William Haley in a detailed account, a prisoner named Boniface managed to persuade Cotton to help his cause by telling him that he was due to come into the sum of £300 from his father but could not get access to it. ‘Out of pure Christian charity,’ wrote Haley, ‘our old parson provided him with counsel, who by some legal quirk, got rid of the capital part of the charge, and the worthy burglar was only found guilty of the minor charge.’ Haley, who had regular and close contact with Cotton, described him as ‘panting for gain’ and alleged that he conspired with the Recorder, Newman Knollys, ‘that infamous, tyrannical villain’, to bring about a sentence of 14 days. Boniface’s promises were empty and when he realised he would not be paid Cotton quite illegally arranged to have Boniface detained in Newgate beyond his sentence.7

Most prisoners had no money to buy their way out, and Cotton does not appear to have profited particularly from his position. His living was comfortable, earning him £400 a year and free accommodation at a time when a male servant might make £16-20.8

According The Morning Post, when he died in Reigate in 1846 at the age of 72, he left ‘few worldly goods’.9

With thanks for pointers in Cotton’s story to Baldwin Hamey of London Street Views.

- Foster, J. (188-1892). Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, 1715-1886 and Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, 1500-1714. Oxford: Parker and Co.

- The Clergy Database

- Other personal diaries of Cotton’s were confiscated by the Aldermen, but this one seems to have escaped detection

- Gatrell, V. A. C. (1994). The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People 1770-1868. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bleackley, H. (1929). Hangmen of England. London: Chapman and Hall.

- This was later rescinded.

- Haley, W. (1825). Life in Newgate. The Newgate Monthly Magazines, or Calendar of Men, Things and Opinions. 1 (September 1824-August 1825). London: R. Carlile. I have not traced Boniface, but Haley’s accusations are so detailed and describe his conversations with Cotton about the case that it is difficult to disbelieve him.

- Sussex Advertiser, 30 Mar 1835.

- 1 Sep 1848.

[…] You can read more on the controversial approach towards the Newgate prisoners by the Rev. Cotton in Naomi Clifford’s blog post on him (here). […]