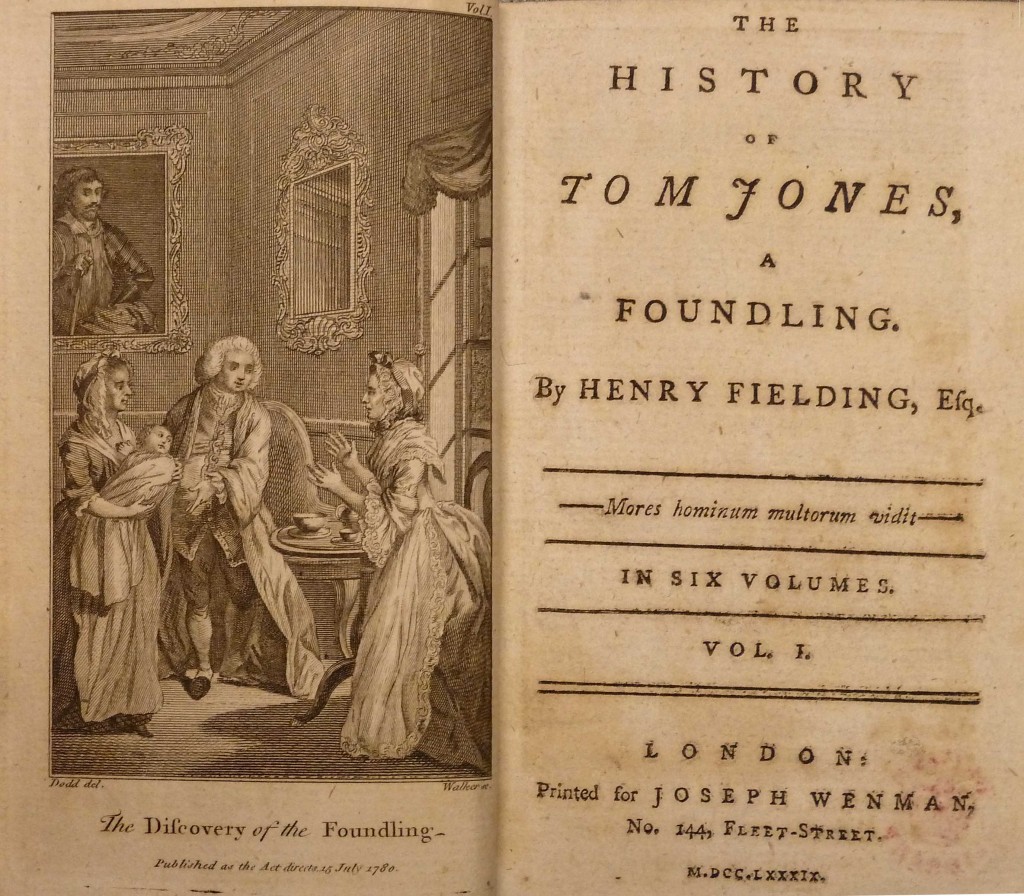

Across the world and throughout history, new mothers who, for whatever reason, feel that they cannot keep their babies have “dropped” them in places where they think they will be found quickly: at the back door of a house belonging to a rich family, in public toilets, in railway station waiting rooms. They want their child to be taken in and, if not loved as they would have done, at least cared for and treated well. It’s a familiar scenario and one which always attracts the attention of the media with its combination of romance, sadness, poverty and possibility. Henry Fielding used it his magnificent History of Tom Jones (1749).

Squire Allworthy wakes up to find a baby, Tom Jones, in his bed. He discovers the mother and kindly sends her into another neighbourhood where she can hide her shame.

On 12 April 1802 Maria Davis and her friend Charlotte Bobbett were hanged on St Michael’s Hill in Bristol for abandoning Davis’s 15-month-old son Richard on Brandon Hill in Clifton. It was accepted that they had not intended the child to die, but they had unwisely chosen a cold, dark night and the child perished from exposure.

On their way to the gallows, they were with difficulty prevented from frequently fainting. At the place of execution, M. Davis, the mother of the child, with the utmost contrition, acknowledged her guilt, at the same time manifesting the greatest distress of mind in having been the means of inducing her unhappy fellow-sufferer to become the accomplice of her diabolical purpose, and earnestly entreating her forgiveness. Both attributed their present deplorable condition to disobedience to their parents, idleness and dissolute company, and requested the Rev. the Ordinary to impress on the minds of the surrounding multitude these lamentable truths, and warn them against the dangers with which such conduct was inevitably followed. After some time spent in exercises of penitential devotion, the wretched victims kissed each other, and then, clasping hands together, were launched into eternity. M. Davies [sic] was about 20 years of age, and C. Bobbett not more than 23. —Gloucester Journal, 19 April 1802

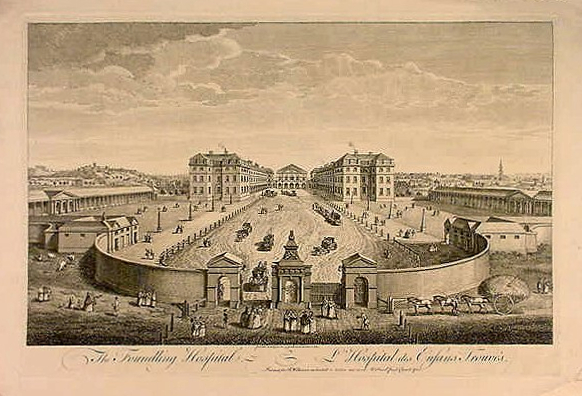

More than 60 years before Maria Davis abandoned her son to his fate, Thomas Coram, a middle-aged sea captain in London, appalled by the frequent sight of infants dead or dying in the streets, decided to campaign for the creation of an institution that would take young children in, care for them, educate them and set them on a path of useful work as apprentices.

Thomas Coram, by William Hogarth

After 17 years, he obtained the support of many rich and well-born men and women and a considerable fund of subscriptions. The Foundling Hospital was established in 1741, initially at Hatton Garden and later in Bloomsbury, “for the maintenance and education of exposed and deserted children”.

Initially, all babies were admitted but the applications became too numerous, and a system of balloting with red, white and black balls was adopted. In 1756, Parliament decided that all children offered should be taken in, that local receiving places should be appointed all over the country, and that the funds should be publicly guaranteed. But that resulted in a flood of unwanted children and huge public expense and the system was abandoned. After that the hospital was forced to restrict the intake to children who had cash-paying sponsors. This system ended in 1801. Now the emphasis was on the character of the mother. She must have been respectable before her pregnancy, unsupported by the father and likely to revert to virtue and resume an honest livelihood after the Foundling Hospital received the child.

The Foundling Hospital

We know very little about the situation of Maria Davis and what led her to her fateful decision, only that her husband had recently died in Ireland. Bristol had no Foundling Hospital like the London institution. Leaving the child at the workhouse was an option, but possibly she had already tried that and been rejected. She may not have had relatives who could step in. She must have run out of choices.

The court did not show the women mercy. The jury had no grounds to turn a blind eye as in many cases of infanticide, when juries would accept almost any evidence as grounds to believe that the mother was not guilty of murder. Here, both Davis and her friend were deemed equally to blame for the child’s death. There could only be one verdict and one punishment.

However, it was the prospect of the dissection of their bodies that upset them the most, and led them, and their families, to plead for mercy. Many people had a real belief in the physical existence of heaven. On Judgment Day the body would rise and ascend – if it were whole. Dissection meant that they would not be accepted.

It was in the gift of the surgeons, not to the court, to reprieve them of this punishment but they refused.

![]()

Huge crowds followed the bodies of Davis and Bobbett as they were cut down and taken a few hundred yards down the hill to Bristol Infirmary, where they remain in the Medical School.

Leave a Reply