In the winter of 1782, James Hurle, a carver and gilder, and his wife Ann Goodwin took their newborn daughter Ann to be christened at St Alfege, in the heart of Greenwich. In time, she was joined by nine brothers and sisters, most of them half-siblings, born to her father’s second and third wives.

A view of the City from Greenwich Park. From William Finden, The Ports, Harbours, Watering-places and Picturesque Scenery of Great Britain Vol. 2. (London: James S. Virtue 1842)

Benjamin Allin, an elderly gentleman, also lived in Greenwich. When Ann was ten, her aunt Jane Hurle took a job as his housekeeper. As Mr Allin grew increasingly frail, hardly ever leaving the house and receiving no visitors, she took over more of his personal management. She helped him with his stocks and shares, and directed him where to sign when he received dividends from his stockbroker. He was acquainted with his housekeeper’s niece Ann, but did not know her well. She regarded Mr Allin with a great deal of interest. She was a clever and resourceful young woman and gradually an audacious plan that would make her fortune formed in her head.

On Saturday 10 December 1803 Ann Hurle crossed the river to the City and enquired at the Bank of England coffee shop for a stockbroker called George Francillon. She told him that she wanted him to take out a power of attorney for Benjamin Allin. Francillon already knew Ann; they may have met when she sold £50 of her own stocks when she came of age in April 1802, but this time she explained that she had been brought up in Mr Allin’s household where her aunt Jane Hurle was his housekeeper and that Allin wanted to gift £500 of Reduced stocks to her as a “reward or recompense for her services to him for some years”. Francillon did as she requested, drew up the document, and gave it to her. She was to get Allin’s signature witnessed by two others.

Ann was back at the Bank of England 11am on Monday with the power of attorney, which was now somewhat worse for wear, which now had Benjamin Allin’s signature on it as well as those of Peter Verney, a cheesemonger, and Thomas Noulden, a carpenter, both living in Greenwich. Before the document could be executed, however, it had to be examined at the Reduced Office, where Francillon left it with a clerk. Meanwhile, Ann went off to sell the stock (she would not be able to transfer into her name without the power of attorney).

When she and Francillon returned to the Reduced Office the inspector of letters of attorney Thomas Bateman told them that there was a problem: the signature was given as “Benjamin Allin” in full whereas the examples of Allin’s signature in the Bank’s files were abbreviated. That was because Mr Allin is not accustomed to writing much, said Ann, but if there was a doubt, she would get a fresh power of attorney and a new signature. Mr Bateman, unwilling to put her to extra expense, preferred that she get Mr Verney, with whom Bateman was slightly acquainted, to sign a second endorsement. He asked Ann how the paper became so “mutilated” and she explained that the dog had got hold of it.

While Ann and Francillon waited in Bateman’s office, Ann mentioned that she had just got married. That will cause another problem, said Francillon, as the power of attorney should be in your married name. Here, seeing her mistake, Ann backtracked furiously. The man she married, James Innes, was “a person of bad character”, she said. He had persuaded her to go to Bristol, where she had married him, not in a church, but in a private house. Within two hours he had stolen her money and some of her clothes, and boarded a ship. Furthermore, he was already married, so she was not actually lawfully married. It is difficult to know why Ann embarked on this seemingly irrelevant fiction. She may have felt that her plan was not going well and marriage would give her additional credibility in the eyes of Francillon and the clerks at the Bank.

Ann left with the power of attorney in her hand, saying she would be back at noon the next day, while Francillon went to Holborn to call on Messrs. Owen and Hicks, attorneys to the Hurle family, who had recommended Ann Hurle to him the previous year, presumably in the matter of selling her own stocks. They told him that they knew nothing about her marriage. By now, he was having serious doubts about the young woman.

The next morning, Tuesday, Ann was back with the document, signed by Peter Verney, which she left with Francillon. His doubts had not abated but he was still not completely sure that it was a forgery, so he asked her to come back on Wednesday. In the meantime, he called on Ann’s father James and asked him to accompany him to see Mr Allin. That interview confirmed his fears.

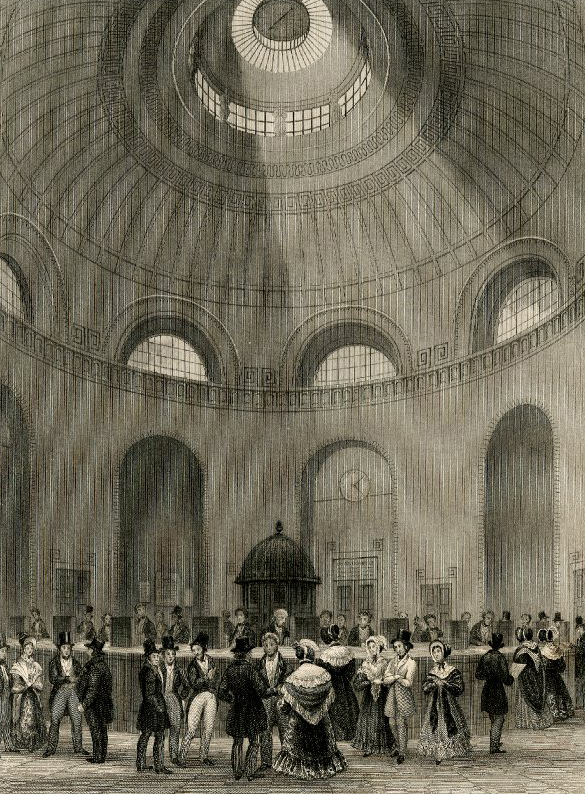

Rotunda at the Bank of England: Payment of dividends. Illustration to ‘London Interiors’ (1841-44). © The Trustees of the British Museum

The following morning, as he walked through the Rotunda at the Bank, Francillon saw Ann in company with a man.

“Miss Hurle, you are come very early this morning. I will be with you in a minute,” he said, and hurried up to the Reduced Office to speak to Mr Newcombe, the principal clerk. He was whisked up to see the accomptant-general and was called in to see the Directors of the Bank, to whom he handed over the power of attorney. At some point during the day, the Bank authorities identified Ann as the person who had at the beginning of December sold £100 of stock in the 3 per cents, by impersonating Elizabeth Hurle, another of her aunts. Downstairs, while waiting in the Bank for Francillon’s return, Ann must have realised that her plan had failed, and left.

Soon afterwards, James Innis, her purported husband, who had accompanied her while she impersonated her aunt Elizabeth, was tracked down and arrested. When he was called before the Bank directors, he claimed that he had also been deceived by Ann, who had told him that she was an heiress. He said he and James Robinson had been to Bristol with her, in order to search for the will of a recently dead relation who had left her a considerable fortune. James Robinson later corroborated his story.

Ann was arrested in Bermondsey, and along with Innes and Robinson, taken before magistrates at Mansion House. She was described as wearing “very plain” dress. She did not yet appear to understand the serious situation she was in and displayed no “suitable anxiety”. Innes and Robinson were discharged – they were clearly not part of a conspiracy – but Ann was fully committed and held at the Poultry Compter to await trial.

The Poultry Compter from Walter Thornbury’s ‘Old and New London, Illustrated’ (1887)

On 11 January 1804 Ann appeared at the Old Bailey, the charges relating only to the attempt to obtain the fraudulent power of attorney and not to the impersonation of her aunt Elizabeth. She was described as “a young woman of education”. William Garrow led the prosecution of what was an easy to prove case. By now, she appreciated the danger she was in, and while the witnesses, Francillon, Bateman, Verney and Noulden, as well as her aunt Jane and a somewhat confused Benjamin Allin, gave evidence against her, she fainted twice. She offered no defence of her own, was found guilty and sentenced to death by the Lord Chief Baron, Sir Archibald Macdonald.

The following Tuesday she and other condemned prisoners were brought up before John Silvester, the Recorder:

He particularly took notice of the case of forgery by Anne Hurle, and said, that her crime was particularly aggravated, by the selection of an infirm and imbecile old man, incapable of management of his own concerns, in order to defraud him, by her artfulness of his property in the funds. It was absolutely necessary, he observed, that the funded property of this Country, so universally diffused, should be guarded by the strictest law, and the infliction of the heaviest punishment. The crime of forgery in all its steps, must necessarily be followed by the punishment of death; for the law must put on all its terrors, to save the public from such a mode of imposition. He then proceeded, in the usual manner, to pronounce the awful sentence of the law.

The only way to delay her imminent death was to plead the belly, and this Ann did (I have written about it previously), but her claim was disproved and she was scheduled to die alongside Mathuselah Spalding, who had been convicted of “an unnatural crime”. A petition on her behalf was presented to the King, but refused. The magnitude of her offence “admitted of no other alternative than the execution of the law”.

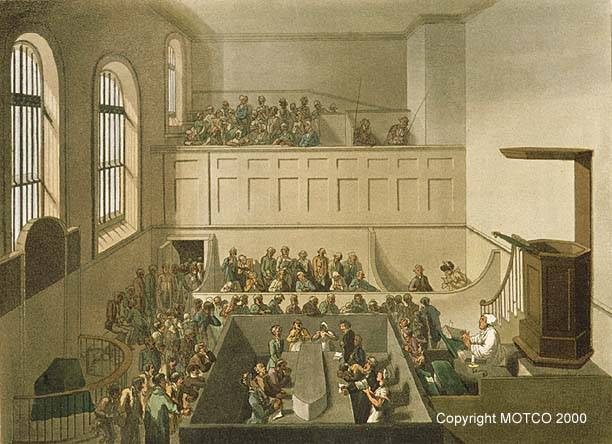

The condemned sermon in Newgate chapel. From Ackermann’s Microcosm of London (1808). Image via MOTCO.

Ann stopped eating. At the condemned service in Newgate, when the doomed were forced to gather around a symbolic coffin, she collapsed. Her parents visited her in the hours before her execution on 8 February. There were further horrors to endure before she got to the gallows. At eight in the morning, dressed in black and wearing a cap, pale and weak, she emerged with Spalding through Debtor’s Door. Accompanied by the Ordinary of Newgate, they were put in a cart and taken a few yards to the top of the Old Bailey near St Sepulchre’s Church. They were to die, not on the New Drop, falling vertically and, it was hoped, less painfully, but the old way, on the common gallows, strangled as the cart on which she stood was pulled away. The reasons for this are not known. A letter in The Times from “Humanus” alleged that it was down to laziness on the part of the staff at Newgate.

“An amazing concourse of spectators were collected on the occasion, all of whom commiserated the fate of Ann Hurle; while that of Mathuselah Spalding …excited sentiments of a very different description,” wrote Bell’s Weekly Advertiser. The crowd was admonished by the Sheriff for its display. Caps were pulled over the faces of the “sufferers”, the nooses adjusted, the horses moved off. Ann Hurle “gave a little scream” and appeared to be “in great agony, moving her hands up and down” for two or three minutes. An hour later her body was cut down, taken inside Newgate to be collected by her parents.

Ann was buried at St Alfege, where she was christened and where other members of the Hurle family were interred.1

Most of the women executed for forgery were involved in uttering or distributing false banknotes. A few others concerned false claims for ship’s prize money or sailor’s wages. Often these crimes would be attempted by women who were barely literate. Ann Hurle’s rank, as someone who was on the edges of gentility, and the fact that she appears to have planned and executed her scheme without the involvement of a man, marked her out as unusual. The Bank, of course, was not impressed and was keen to show that such crimes would not be tolerated. The public, however, were anxious about the amount of blood shed, often for trivial amounts. Ann had attempted to walk away with a huge amount of money, but she was young and “interesting looking” (a catch-all euphemism, probably meaning young and attractive) and to see such a life curtailed, to deny her the chance of rehabilitation, caused distress to many.

Change was slow to come. Sir Samuel Romilly, among others, appealed for changes to the law. It was not until 1832 that the death sentence for forgery, and a host of other crimes, was abolished. The last woman to die in England and Wales for forgery was Sarah Price, for uttering, in 1820.2

- Only murderers were dissected.

- Morning Post, 21 December 1803; Kentish Weekly Post or Canterbury Journal, 23 December 1803; Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 25 December 1803 and 12 February 1804; I am indebted to Bob Hammersley’s website for transcripts of articles in The Times and to capitalpunishmentuk.org.

Leave a Reply