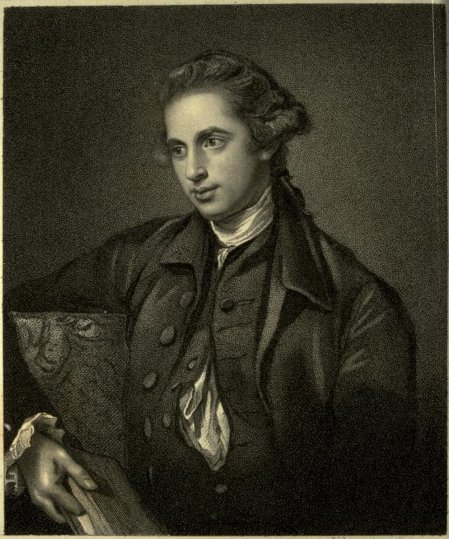

Judge George Hardinge, the Eton-educated, poetry-writing, early supporter of the Philanthropic Society, had real admiration for Mary Morgan. She was, he later wrote to the the Rev. Dr. Horsley, Bishop of Asaph:

…pretty and modest; [her countenance] even had the air and expression of perfect innocence. Not a tear escaped from her, when all around her were deeply affected by her doom; yet her carriage was respectful her look attentive, serious, and intelligent… It appeared she had no defect of understanding, and she was born with every disposition to virtue…”

Yet, he lamented, “there was not a single trace of Religion to be found in her thoughts. Of Christianity, she had never even heard, or of The Bible; and she had scarce ever been at Church [his italics].” Mary’s lack of religious understanding may have contributed to the judge’s decision that he had no option but to send her for execution.

At a time when compassion was routinely shown to unmarried women, especially those in service, whose babies were found dead in suspicious circumstances and only two years after the law was changed to accommodate juries’ almost routine refusal to convict such women of murder, why did Mary end up at the end of a rope? Why did this uneducated 17-year-old suffer while others guilty of similar crimes who appeared before Hardinge survived? And why did this ostensibly compassionate judge resolutely refuse to respite her?

Mary worked as an under-cook at Maesllwch Castle,1 just over a mile from Glasbury, where Mary was brought up by her parents Rees and Elizabeth Morgan.2 Maesllwch was the home of Walter Wilkins, until his death in 1828, the Whig MP for Radnorshire, and a former High Sheriff of Radnorshire and also of Breconshire, his wife and two adult sons, Walter and Jeffreys. The household must have been substantial, as evidenced by the fact that the kitchens were so busy on the afternoon of Sunday 23 September, when Mary Morgan said she was too ill to work and crawled up to her bed, that rather than struggle on without her, the housekeeper, felt the need to call in Margaret Havard to replace her.

The servant women were concerned about 16-year-old Mary, and probably not a little suspicious of the reason for her sudden inability to work. The housekeeper came to her room to give her a drink of warm wine and at some time between six and seven Elizabeth Evelyn, the cook, brought tea, returning half an hour later with Margaret Havard. The instant they entered the room their suspicions were confirmed. The record says, “from some particular circumstance which [Elizabeth Evelyn] saw”3 they knew that Mary had given birth, and said so. In any case the distinctive odour present after childbirth would probably have been enough to give the game away.

“Mary strongly denied it with bitter oaths for some time,” said Margaret Havard later, but then Mary suddenly admitted that it was true and told them that the baby was buried in the mattress, and there they found her “amongst the feathers”, her head nearly separated from her neck. The weapon, a penknife that Mary used to cut up chickens, was discovered under the pillow.4

A coroner’s inquest held two days later decided that Mary “not having the fear of God before her eyes, but moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil” had assaulted her child and made a “mortal wound of the length of three inches and the depth of one inch” with her penknife and that the child had died instantly. She was arrested but was not taken on the 25-mile5 journey to the country gaol at Presteigne to await her trial at the next assize until she was sufficiently recovered from the birth.6

Mary first arrived at the castle to work at about the age of 15 or 16 and seems to have soon attracted the attention of Walter Wilkins the younger. George Hardinge’s wrote that Mary’s “young master” “intrigued with her”, implying a sexual relationship, but that he was not the father of her child. (A rumour that he was extended into the 20th century.7

Rather, when she found herself pregnant by a co-worker (a waggoner, according to the Chester Courant8), who refused to maintain the child, she appealed to Walter for help.

Hardinge was impressed by Mary’s perverse sense of honour:

The young Squire, though her favourite gallant, was not the father; but she did him justice in reporting, that, when he was apprized of the pregnancy he offered her to maintain the child when born, if she would only say that he was the father… although it would have saved her child’s life and her own, she would not purchase these two lives by a falsehood.”

When she complained of discomfort from the pregnancy, the waggoner offered her herbs, but she refused them, fearing that they would cause a miscarriage. Probably, like many a teenager in her situation, she simultaneously looked forward to the coming child and dreaded its impact, just as she expected the father to stand by her but anticipated that he would not. As her time approached and certainly after labour started, Mary must have come to accept that her situation was desperate: the birth of the baby would meant the end of everything. A life of shame, of abject poverty or in the workhouse was in prospect. She made a decision.

She told the court about that decision in words that damned her:

I determined, therefore, to kill it, poor thing! Out of the way, being perfectly sure that I could not provide for it myself.”

On 11 April 1805 Mary came up before Justice Hardinge. The High Sheriff, Charles Rogers, taking pity on her, appointed and paid for a defence counsel, Richard Bevan (or Beavan). The trial itself was a straightforward affair. Some historians have claimed that Walter Wilkins the younger was among the jurors, but this is not proved.9

The servant women who had given evidence at the coroner’s inquest, including Elizabeth Evelyn and Margaret Havard, repeated their testimony. Morgan, of course, could not enter the witness box and give her side. All she was entitled to do was to speak at the end and we have no evidence that she did so. After the jury returned a verdict of guilty of murder, Hardinge addressed her. He was in tears, as were the entire court, but she remained dry-eyed.

Hardinge was known for his emotional addresses to the convicted, many of which were published.10

His words to Mary were carried in The Cambrian11 and picked up in newspapers across the country. He spoke about the murder of her child (“the offspring of your secret and vicious love”), Mary’s likely reasons for killing her (“Had it lived, you might have lost your place… You might have lived in poverty as well as shame”) and included numerous admonitions of her “criminal intercourse,” “criminal passions,” “depraved self-indulgence” which had led her first to “the sin of imposture” (concealing her pregnancy) and then to the murder of “the offspring of your own guilt.” She was to be made an example of:

Had you escaped, many other girls, thoughtless and light as you have been, would have been encouraged by that escape to commit your crime with hope of your impunity. The merciful terror of your example will save them. Desperate acts like these often escape from punishment. Merciful juries – merciful rules of law – and merciful judges give occasion to that impunity. If it is a defect, I hope it will never be repaired. But the same juries – the same law – and the same judges are firm to their trust in a case like yours.”

He ordered her to be “taken from hence to the place from whence you came, and from thence to the place of execution, the day after tomorrow. You are there to hang by the neck till you are dead: your body is then to be dissected and anatomised. But your soul is not reached by these inflictions. It is in the hand of your God – may that fountain of love show mercy to it when it shall appear before him at the day of judgment!”

Mary was led away back to the gaol, to the accommodation for condemned prisoners on the first floor. Here her former composure disappeared and, according to the Chester Courant, she became “much agitated”. The following day, Friday, her father visited her and she appeared calmer, but that, again according to the newspaper reports, was because she was entertaining hopes of an escape. We cannot know whether or not this is true, and Hardinge himself does not mention it in his letter to the Bishop, merely stating that “Mary took it for granted that she would be acquitted” and that she had ordered “gay apparel” in the expectation that Wilkins (the “young master”) would write to the judge and bring about a reprieve (Wilkins, according to Hardinge, refused to help her). Probably only when all hope had expired did Mary accept the consolations of the Chaplain, the Rev Smith, admit her guilt and prepare for the Christian death Hardinge wished for her.

Newspaper reports stated that she went to the gallows at Presteigne the following day “truly penitent.” She had cost the county £1 and 19 shillings for her coffin, shroud, cap and church fees, and she was buried in unconsecrated ground in St Andrew’s churchyard in Presteigne. The archives reveal no trace of a petition for mercy, either from the judge or from Mary’s friends and family.12

***

What made Mary’s punishment notable was that, while the judicial execution of women was uncommon, it was highly unusual to execute teenage girls. As Anne-Marie Kilday has pointed out,13 of the 149 women indicted for murdering their babies between 1730 and 1804 at the Court of Great Sessions in Wales only seven were convicted and two executed, the last one in 1739. After her case, up to 1830, 46 were indicted and none was convicted.

Hardinge was much criticised for Mary’s harsh punishment and it not hard to see why. Mary was young and attractive, which made her a suitable candidate for sympathy. There were strong rumours that her pregnancy was the responsibility of the “young master”; there was even talk that Hardinge himself, a distant relative of the Wilkins family, was the father. In either case, that would imply that she had been imposed upon or at the least seduced by her social superiors and was therefore more deserving of compassion. No consideration appears to have been given to the desperate situation she was in, in labour, alone and seemingly friendless, nor to the possibility that she had suffered a catastrophic mental breakdown at the time of her delivery. Her demeanour in court was interpreted as sullenness rather than the manifestation of a state of deep denial.

There is no doubt that Hardinge felt genuine compassion for the child Mary had destroyed. He was revolted by infanticide, asserting in his letter to the Bishop that “In our part of Wales it is thought no crime to kill a bastard-child” and bemoaning the fact that “there has not been a conviction at the Old Bailey for this crime during a period of twenty years.” In Ireland, “the habit of exposing children … rages like a pestilence.” Hardinge, through tears, had berated Mary in court: “There is not a more sacred object of that parent’s love (whose children we all of us are) than a new-born child.” But he was unable to show mercy to Mary, scarcely more than a child herself. Only a week previously at Brecon a similar case had a very different outcome. Hardinge regretted that the jury found Mary Morris, who had killed her child with scissors, guilty only of concealment. He imprisoned her for the maximum term allowed, two years.14 When Mary Morgan’s jury returned its verdict, he saw his opportunity to make a point.

For Hardinge, the recent change in the law on the murder of infants was a retrograde step. Before 1803, when Lord Chief Justice Ellenborough took the entirely pragmatic view that trials of women for infanticide were a waste of time because there was so little likelihood of conviction and proposed the repeal of the 1624 statute as part of a package of changes.15 Ellenborough, not a liberal by any means, wanted to ensure that women who killed their babies were punished in some way. If they could be found guilty of concealing a death they could be imprisoned for up to two years. As Hardinge explained to the Grand Jury at Brecon in August 1805, just four months after Mary was executed, he felt he “dare not as a Judge arraign” this new law, but he was “not able to fathom” it.16

The law Hardinge wanted to retain was the 1624 statute had held that unmarried women whose bastard children were found dead were automatically assumed to be guilty of murder, except where they could bring forward a witness who could testify that the child was born dead or died of natural causes. It was among the few laws of England in which the guilt of the accused was assumed at trial. It was up to the woman to prove that she was innocent. Of course, it did nothing to deter unmarried women from falling pregnant and, when they found themselves facing destitution, from doing away with their babies, and by the end of the 18th century juries, unable to bring themselves to condemn the unfortunate women in the dock, were routinely acquitting them. A raft of legal defences developed to allow them to do so in conscience, from “benefit of linen,” the claim that asking to borrow or acquiring baby linen before a birth, to lack of help during the delivery (typically the woman might have fainted while alone), to basic midwifery mistakes (failure to catch the child while the baby is being born or neglecting to tie the cord). Concealment, of course, could occur anywhere around the house, in trunks, pails, rubbish heaps, privies and coalbins. It seems odd that Mary Morgan did not search out a nook at Maesllwch Castle and try to give birth there, and then to claim that some accident had befallen the child. However, she most likely knew nothing of the law, was not acting rationally.

Hardinge called infanticides “the vice of the poor,” especially those in service, and blamed their lack of religion and of education. “In proportion to the undisciplined and savage characters of the poor, this offence is more or less prevalent.”

It is at this point that we in the 21st century heave a weary sigh. What would George Hardinge, born in a manor house in Kingston upon Thames, the son of Sir Nicholas Hardinge, educated at Eton and Cambridge, former MP, composer of verses in Latin and English, have known about the pressures on an underage servant pregnant, in labour, alone and facing the privations of the workhouse? Despite his charitable endeavours – he was a successful fundraiser for good causes and became vice chairman of the Philanthropic Society, which sought to help the young homeless children begging and stealing on the streets of London by training them in cottage industries – he had no insight into Mary Morgan’s state of mind at the time she committed this dreadful crime, nor was he interested in it.

Georgian justice was mercurial; it operated by condemning many and reprieving some, sending them away as free labour in the colonies, ordering them to perform hard labour in prisons, or in a few cases letting them off entirely; that way, the authority of the state could be imposed on the masses. The hope was that unpredictable mercy was enough to keep people in check while keeping the flow of blood at level acceptable to the general public, especially the middle-classes. Notable examples were required as assertions of the state’s power and to reinforce the message of deterrence. Hence, Hardinge’s words to Mary: “the merciful terror” of her example will save other girls from a similar fate.

It seems the pinnacle of hypocrisy that Hardinge’s made repeated visits to Mary Morgan’s grave on his subsequent visits to Presteigne, during which he shed tears, but to him their purpose was “to revive the impression which she made on his memory”. He did not blame himself for her death but he was keen to show that he had the appropriate levels of sensibility, that peculiar Georgian spin on sentimentality, and employed his much-lauded facility for poetry to memorialise her:

Flow the tears that Pity loves

Upon Mary’s hapless fate;

It’s a tear that God approves:

He can strike, but cannot hate.

She for an example fell,

But is Man from censure free?

Thine, Seducer, is the Knell,

It’s a messenger to thee.17

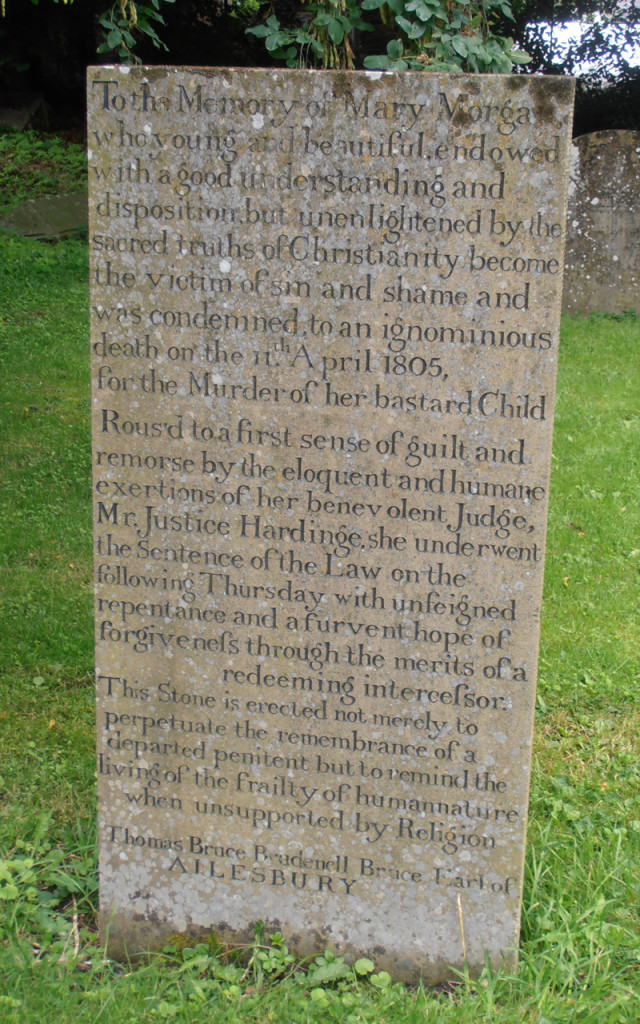

As a further response to public feeling, a friend of Hardinge’s, Thomas Bruce Brudenell Bruce, Earl of Ailsbury, erected a stone on Mary’s grave, the inscription perfectly reflecting Hardinge’s opinions and eulogising him as a “benevolent judge.”

To the Memory of Mary Morgan who young and beautiful endowed with a good understanding and disposition but unenlightened by the sacred truths of Christianity become the victim of sin and shame and was condemned to an ignominious death on the 11th April 1805 for the Murder of her bastard child. Rousd to a first sense of guilt and remorse by the eloquent and humane exertions of her benevolent judge, Mr Justice Hardinge, she underwent the sentence of the Law on the following Thursday with unfeigned repentance and a furvent [sic] hope of forgiveness through the merits of a redeeming intercessor. This Stone is erected not merely to perpetuate the remembrance of a departed penitent but to remind the living of the frailty of human nature when unsupported by Religion.

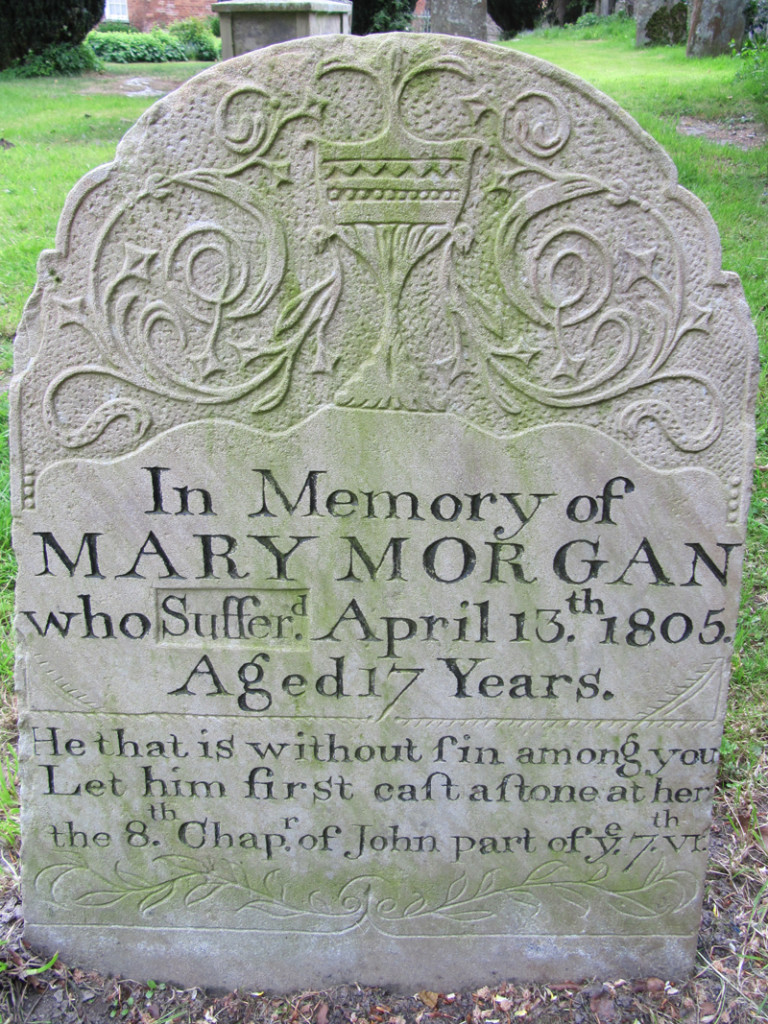

An anonymous donor countered this with another stone, simply inscribed:

In Memory of

MARY MORGAN

who Suffrd April 13th 1805

Aged 17 Years.

He that is without sin among you

Let him first cast a stone at her

the 8th Chapr of John part of ye 7th VI.

In 1818, more than ten years after she was killed and two years after Hardinge died (at Presteigne ironically enough) Thomas Horton,18 a playwright and comedian19 made use of Mary’s death. In “Elegy Written in the Church Yard of Presteign,” written in emulation of Thomas Gray’s 1750 work, he aimed to impress on “young females in the same sphere of life in which poor Mary Morgan moved” the “dreadful consequences a single deviation from the path of virtue may ultimately lead to,” in the apparent belief that young girls would be mindful that one episode of intercourse could, and probably would, lead directly to the gallows. The poetry is indifferent (Mary was “sweet as the sunshine sparkling on the stream”) but the work serves to illustrate the invidious position of women. They had little power over their own lives, about a third of a man’s earning power, and no position in the structure of society, yet they must also be super-angelic: good, submissive (“virtuous, lovely,” “meek as the daisy” in Horton’s phrase) and, above all, careful to “shun the poison of a flatt’ring tongue”. There was no mention of the owner of the flatt’ring tongue nor of his role in pushing young women towards the waiting noose. The pamphlet attracted over 300 subscribers, no doubt many of them also congratulating themselves on their sensibility.

In his letter to the Bishop, Hardinge called Mary Morgan’s death “a Provincial Tragedy,” not in order to dismiss it as unimportant because it happened far from London, but to draw attention to what he felt was the neglected crime of infanticide, which he claimed was was particularly common among the poverty-stricken and ignorant poor of Wales. In Hardinge’s world view, girls like Mary were responsible for her own ignorance of the Christian values that would have saved her: “She had no religious abhorrence of her crime, till a few short hours before she terminated her existence” (my italics.)

What Hardinge could not see was that his lack of understanding of Mary’s life and of his own role in the process of judicial retribution itself resulted in a death as tragic as the one that brought Mary before him.

- The building has been substantially altered in the mid 19th century.

- Anne-Marie Kilday, A History of Infanticide in Britain, c. 1600 to the Present. Palgrave Macmillan (2013).

- Depositions at the inquest (WALES 4/533/3) quoted in Radnorshire Society Transactions, “Mary Morgan: Contemporary Sources” by Patricia Parris, Vol. 53 (1983), p.57-63.

- Depositions. Ibid.

- 40km.

- The gaol was on the site of the Shire Hall (now the Judge’s Lodging).

- It is accepted in “A Gravestone at Presteigne and It’s Story” in Radnorshire Society Transactions, Vol. 13 (1943), p 60-64.

- 14 May 1805.

- Patricia Parris. Ibid.

- The Miscellaneous Works, in Prose and Verse, of George Hardinge Esq., London: J. Nichols, (1818).

- 27 April 1805.

- Patricia Parris. Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Illustrations of the Literary History of the Eighteenth Century, Vol. 3, page 129, “A Charge intended to have been delivered to the Grand Jury in April 1816”.

- This was not entirely a reforming measure as many new crimes were added to the Bloody Code.

- Charge delivered at the Assizes for the County of Brecon, August 26, 1805.” The Miscellaneous Works, in Prose and Verse, of George Hardinge Esq. London: J. Nichols (1818).

- Quoted in A Gravestone at Presteigne and It’s Story. Ibid.

- Thomas Horton, comedian, was later author of Nell Gwynne, the City of the Wye, Or The Red Lands of Herefordshire: An Historical Play.

- The word was used more in the sense of entertainer than of joke-teller.

The men responsible for the babies never seem to be involved .

I don’t fault the judge nor the jury as they followed the law. I didn’t know that the law was enforced so rarely, though. I did know about the excuses of a child found in a privy– where the woman said she didn’t know she was in labor or that the baby would come while she was trying to defecate. Did read cases where the woman wasn’t arrested because she had amassed a layette and asked friends to be Godparents. It took years for the government to close down baby farms. Only recently that many places have enacted safe places to leave a baby because abandonment , starvation, and murder is still much practiced. The Foundling hospital was founded, I read, to have a place the babies could be placed instead of killing them.

If the “fathers” of those children acted honorably there would be no children to kill.

Hi nmayer2015n – Thanks for your comment. Such an interesting case. I agree, the father of the child left Mary in a terrible position, but he may have been married or otherwise unable to stand by her (I am not excusing him). To my mind, Hardinge was the most to blame for the outcome. He could have respited Mary himself or submitted a plea to the King, but he was clearly determined to take the opportunity of holding her up as an example. I have no doubt that he thought he was making a difference, that is preventing future infanticides. He was deluded, of course. I have just come across a strange little book about the case (strange in that it is such a personal take on it): On the Morning of Her Day. Worth a look. – Naomi

I am fascinated by this case. Could you share more details about the book you recommend: On the Morning of Her Day? I can’t seem to track it down on the internet.

Hi Allison – I just found it for sale on Abebooks (UK). A copy here: https://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=30919006500 – Best wishes, Naomi

It’s striking that on the ‘alternative’ headstone, the term “Suffer.d” is squashed into a panel inset into the face of the stone. It seems pretty certain that it’s an afterthought – the original inscription (“died” in a font matching the rest of the stone would pretty much fit that space precisely) has been chiselled off. Because the donor was anonymous, there are presumably no records relating to this stone…. but it would be fascinating to know in what circumstances the last-minute amendment was made!