When Sarah Lloyd appeared at Bury St Edmunds Assizes on 20 March 1800 on capital charges, she offered these meagre words in her own defence:

It was not me, my Lord, but Clarke that did it.

In court she could not even call any witnesses to her good character, as the only one who could have attested to it was her employer, who happened to be the principal victim and, understandably, declined to help.

Lloyd had been employed as a maidservant for Sarah Syer, an elderly widow who lived with a companion, Elizabeth Hoborough, in Hadleigh, near Ipswich. Unknown to her mistress, Lloyd had started a relationship with Joseph Clarke, a plumber and glazier from a respectable local family. Lloyd was illiterate, did not know her own age (she was thought to be between 18 and 23) and was never taught the Bible.

While Mrs Syer and Mrs Hoborough slept, Lloyd and Clarke stole items from the house including clothes, handkerchiefs, a watch and about 10 guineas in cash. While Mrs Syer slept, they carefully slid her pockets, which contained her cash and other precious items, from their hiding place behind her head, between the bolster and the pillow.

Clarke and Lloyd fled after trying to cover their tracks by setting fire to the house, but their efforts failed and they only managed to destroy an outhouse. They stashed the loot at Lloyd’s family home in Naughton, five miles away. If she was accused (as she was sure to be) Clarke advised Lloyd to say that two soldiers billeted nearby had inveigled her into it.

© Copyright Robert Edwards and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

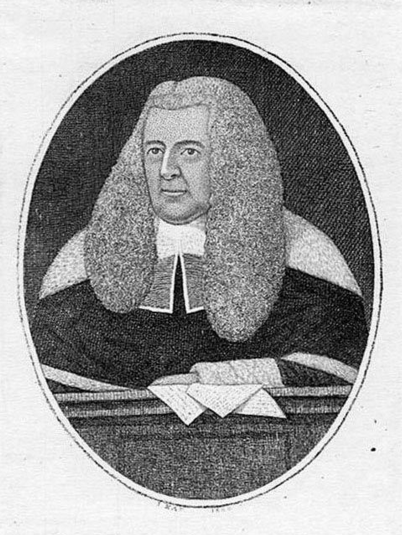

A few days later, a few miles from Hadleigh, a local man recognised Lloyd, who ran across the fields when she realised she had been recognised. Her efforts to hide in a ditch were to no avail and she was taken to a local tavern to await the constable. She was quick to confess and revealed the location of the stolen goods: they were at her family’s place in Naughton. The cash was never found. Soon Clarke was also arrested and, after their indictment by a grand jury, the two of them were held in Bury jail until they appeared before Sir Nash Grose at the next Assizes.1

It was a cut-and-dried case. There was no doubt that Lloyd had robbed her mistress – her affidavit to the magistrate stated her part in the crime – but during the trial the charges against Clarke were dropped, but this was perhaps less a product of misogyny than of the simple fact that Lloyd had confessed but Clarke had not, and that, apart from her word, there was no other evidence against him. Lloyd was found not guilty of burglary2 but guilty of stealing in the dwelling house to the value of 40 shillings.

The remarks of Judge Grose show that Sarah, as a female and as a servant, was deemed to have transgressed on many levels:

A servant robbing a mistress is a very heinous crime; but your crime is greatly heightened; your mistress placed implicit confidence in your; you slept near her, in the same room, and you ought to have protected her… and though this crime was bad, yet it was innocence, compared with what followed: you were not content with robbing her mistress, but you conspired to set her house on fire, thereby adding to your crime death and destruction not only to the unfortunate Lady, but to all those whose houses were near by.3

He moved towards the fatal words:

“I have to announce to you that your last hour is approaching; and for the great and aggravated offence that you have committed, the law dooms you to die.”

He could see no grounds for a recommendation to mercy and advised her to repent and seek God’s forgiveness.

Events would have proceeded along the normal course and Lloyd hung within days but for remarks Lloyd made to the Reverend Hay Dummond, the rector of Hadleigh, when he visited her in the condemned cell of Bury jail. She told him she had been seduced by Clarke, who was in the habit of visiting her for sex. She had regarded him as her husband. On the night of the crime, she had told him that she was pregnant and he had promised marriage.

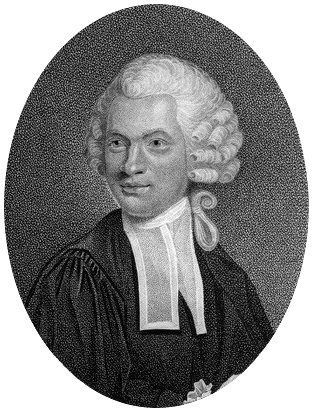

This disclosure caused Drummond to adjust his view of her. She was less a sinner who had acted as a free agent and more Clarke’s object, who had to do his bidding. This was entirely in accordance with attitudes to women. They should be subservient to men and in law, if married, they were not even viewed as separate legal entities. Drummond set about organising a petition for mercy from the King and asked Capel Lofft, a local magistrate who had sat on the grand jury that indicted Lloyd, for help.

Educated at Eton and Cambridge, Lofft was a one-time radical barrister, who opposed the American War and supported the aims of the French Revolution. In middle age his revolutionary fervour had cooled somewhat and he was now a Suffolk magistrate, but he retained a humane approach to his social inferiors.

Lofft visited Lloyd in the condemned cell at Bury and immediately took up her cause with a fervour bordering on obsession. Together with Mr Orridge (the prison chaplain) and the governor he asked the Suffolk under-sheriff to delay the execution, citing legal precedent; he also wrote to the Home Secretary, the Duke of Portland, and the former Prime Minister, the Duke of Grafton. His efforts were to no avail. Portland angrily rejected Lofft’s interference in the process of execution. Lloyd, he wrote, would be executed on 22 April.

We are lucky to have a description of Lloyd, from one of Lofft’s letters:

She was rather low of stature, of a pale complexion, to which anxiety and near seven months’ imprisonment had given a yellowish tint. Naturally she appears to have been fair, as when she coloured, the colour naturally diffused itself. Her countenance was very pleasing, of a meek and modest expression, perfectly characteristic of a mild and affectionate temper. She had large eyes and eyelids, a short and well-formed nose, an open forehead, of a grand and ingenuous character, and very regular and pleasing features; her hair darkish brown, and her eyebrows rather darker than her hair: she had an uncommon and unaffected sweetness in her voice and manner. She seemed to be above impatience or discontent, fear or ostentation, exempt from selfish emotion, but attentive with pure sympathy to those whom her state, and the affecting singularity of her case, and her uniformly admirable behaviour, interested in her behalf.

Lofft also hinted that Lloyd may not have not been of average intelligence.

very young and wholly uneducated woman, naturally of a very tender disposition, and, from her mild and amiable temper, accustomed to be treated as their child in the families in which she had lived, and who consequently had not learned fortitude from experience either of danger or hardship.

There was no mention of a baby (she may have suffered a miscarriage) or therefore of “pleading her belly.”

On the morning of the execution, according to Lofft, Lloyd “took an affectionate, but composed and even cheerful, leave of her fellow-prisoners, and rather gave them comfort than needed to receive it.” She gave him her few posessions: her earrings were to be passed on to her sister, a cushion to a little girl at Clarke’s house, her clothes to her mother, to be divided between her sisters, with some going to two fellow prisoners. She was dressed in white with a black ribbon on her bonnet and arms and a black sash around her waist.

Lofft sat beside her as she was conveyed, her arms pinioned, in the cart to the place of execution. The day was windy and pouring with rain, and he held an umbrella over her. Then he mounted the scaffold with her and for 15 minutes addressed the crowd, denouncing the Home Secretary, justifying his intervention and praising Lloyd, who wept beside him.

As her time approached, Lloyd was asked if she had anything to say, but she replied that she had told her mind, and “what she said was true respecting Clarke.”

According to Lofft,

She dignified, by her deportment, every humiliating circumstance of this otherwise most degrading of deaths, and maintained an unaltered equanimity and recollectedness, herself assisting in putting back her hair and adjusting the instrument of death to her neck. 4

A prayer was said and she was “launched into eternity, amidst the tears of a number of her sex.”5

For Lofft, Lloyd was a paragon of feminine submission even as she died:

After she had been suspended more than a minute, her hands were twice evenly and gently raised, and gradually let to fall without the least appearance of convulsive or involuntary motion, in a manner which could hardly be mistaken, when interpreted, as designed to signify content and resignation.

Lofft organised the interment, which was to be at eight that evening in the abbey burial grounds. A thousand people had gathered there when he turned up with the body an hour late. He told them that Lloyd’s mother had attempted suicide when the appeal failed and reminded them of Lloyd’s respectability (“for respectability was not to be confined to rank or riches, but is applicable to every person who gains his livelihood by honest industry.”) There was commotion when Lofft alleged that the authorities had denied Lloyd a burial service (this was denied) and the event became an opportunity to voice suppressed class anger, with shouts of “The rich have everything, the poor have nothing.”

This final act of defiance by Lofft proved was too much for the authorities. Fellow JPs complained to the Home Secretary, and Portland promptly removed him from the bench. Ten years later, he resumed his law career with an appointment as recorder in Aldborough but later left England to live on the Continent. He died in 1824.6

Lofft’s view of Lloyd may have excited the most attention from the authorities, but it was perhaps not the prevailing opinion.

“Had this unhappy girl been instructed in the rudiments only of Christianity, of which she was utterly ignorant, this crime probably would never have been committed,” intoned the author of the trial report, bewailing the fact that she “lost her virtue, her sense of rectitude, and her life,” as if there was an inevitable progression from one pit of sin to the next.

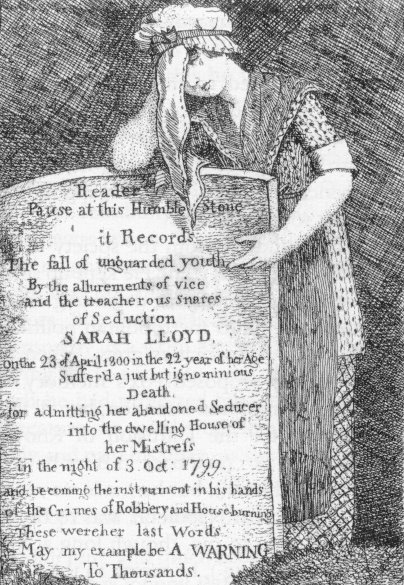

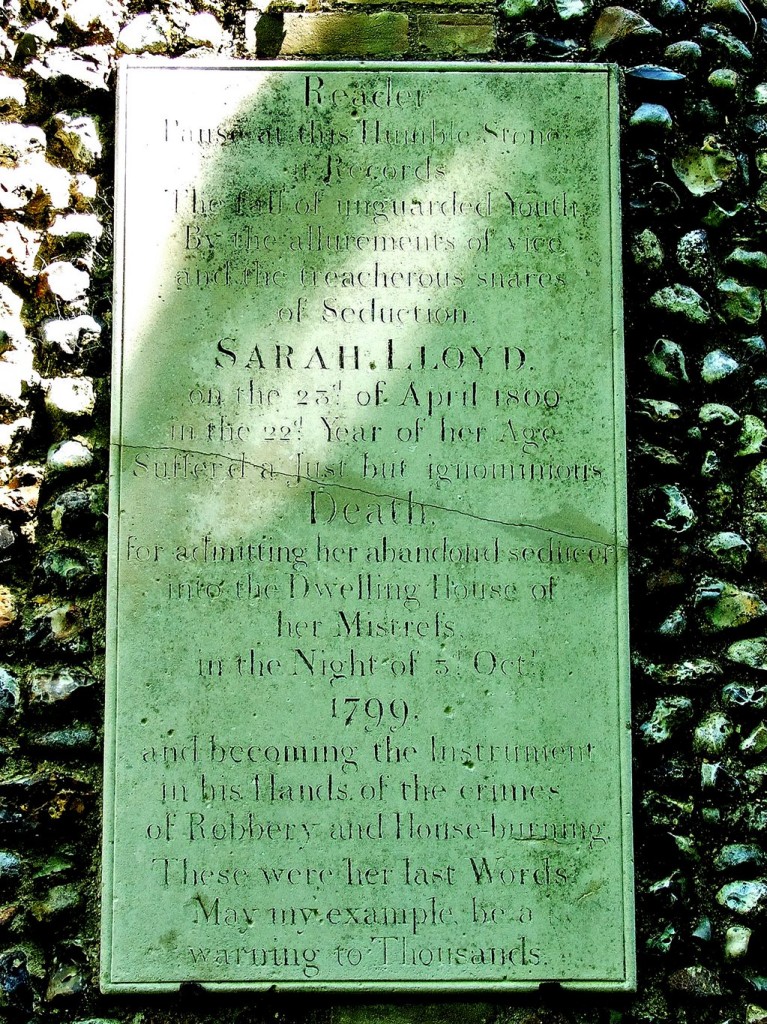

A stone, still standing in the graveyard at Bury Abbey reflects the more conventional view of Lloyd’s transgressions.

Reader,

Pause at this Humble Stone.

It Records

The fall of unguarded youth

By the allurements of vice

And the treacherous snares of Seduction

SARAH LLOYD

on 23rd April 1800

in the 22 year of her Age

Suffer’d a just but ignominious

Death

for admitting her abandoned Seducer

into the dwelling House of

her Mistress

in the night of 3 Oct 1799

and becoming the instrument in his hands

of the Crimes of Robbery and House burning

These were her last words

May my example be a

warning to Thousands

- Trial of Joseph Clarke, the Younger, and Sarah Lloyd, at the Assizes, held at Bury St Edmund’s, March 20, 1800, Before Sir Nash Grose, Knt. W. Notcutt.

- Burglary, by definition, has to take place at night and to involve breaking in to a property; Lloyd let Clarke into the house from the inside.

- The judge appears to have ignored the fact that Lloyd was not convicted of arson; Lloyd alleged that Clarke had set the fires in Mrs Syer’s house.

- William Jackson, The New and Complete Newgate Calendar; or, Villany displayed in all its branches, Vol 6.

- Ipswich Journal, 26 April 1800.

- I am indebted for much of this story V.A.C. Gatrell’s The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People 1770-1868 (OUP, 1994), especially.

sarah lloyd should not have recieved the death sentence, sarah was niave ,,clarke should have been found guilty, this was a complete miscarriage of justice.

Nov 18th 2023, Today I visited the site of sarah Lloyd’s headstone in the grounds of Bury st Edmunds Abbey and her place of execution hangman’s Hill now called thingo hill, Sarah’s case should be reopened as her only crime was falling for clark who in my opinion was as guilty as sin,

I completely agree, Michael. Sadly, Sarah made the mistake of confessing and took the rap. Many people could see the injustice of her punishment (and this was a time when the law was, to us, astonishingly harsh on those committing property theft), although sadly for Sarah the Establishment needed occasional examples to terrify the “criminal classes”. An appalling, unnecessary and pointless death.

I feel that she should be cleared of full responsibility for this crime and Clark, in retropect, should have the records changed to his full responsibility for the crime of arson as well as using Sarah Lloyd in committing thus crime

Joseph was more guilty of the crime than Sarah Lloyd. She shouldn’t have done what she did but he was clearly.

I am trying to find out where she hanged, can’t find the information.

All the information I have is “Bury St Edmunds” – sadly I don’t know the exact site. Later executions were conducted outside the County Gaol. – Naomi

St Edmundsbury chronicle also says Clarke confessed on his death bed aged sixty five years of age,

Hangman’s Hill, now known as thingo hill bury st Edmunds

Retrieved from the st emundsbury chronicle,Sarah Lloyd was hanged at the tayfen meadows,