Over two hundred years after her death, Margaret Catchpole (1762–1811) is remembered by many – for the things she was not and the things she did not do, largely because someone who never met her wrote her purported biography, which was largely a work of fiction. Ironically Margaret Catchpole’s life was extraordinary enough without this.

So what did Margaret do that was so noteworthy?

Who was Margaret Catchpole?

Margaret was born in Suffolk, probably at Brandeston, and registered by her mother Elizabeth Catchpole at the church of St Andrew and St Eustachius at Hoo on 14 March 1762. Her mother was unmarried and her father’s identity is unknown. Elizabeth later married Robert Nunn and went on to have five legitimate children. Four died of disease, probably typhoid, three of them expiring while living in the House of Industry (the workhouse) at Melton, where Elizabeth succumbed herself in 1785, with her husband following four years later. It is safe to say that Margaret had a difficult start to life.

Margaret was put into domestic service with a series of local families, probably starting at the age of 11, as was usual for girls. At some time before this, she learned to read and write, to sew and to ride a horse, all skills important in her story.

Her life continued in an unexceptional way, until in May 1794, aged 32, she joined the household of John Cobbold (1746–1835), the wealthy head of an Ipswich brewing family, and his wife the poet Elizabeth or Eliza Knipe (1765–1824). Aside: Eliza was the model for Charles Dickens’ character Mrs. Leo Hunter in The Pickwick Papers.

The Cobbold household, initially based at The Cliff in Ipswich and later the Manor House at St Margaret’s Green, was warm-hearted, generous and extremely populous. When Elizabeth married the widowed John in 1791 she took on the care of his 15 children by his first wife, and then went on to have seven of her own. Her son Richard was born in 1797 and it was his enhanced account of Margaret’s life that revived her reputation long after she was dead.

Margaret left the Cobbolds after 18 months but immediately became ill with some unspecified and recurring condition. Between periods working as a servant, she returned intermittently to live with her aunt and uncle but ended up in lodgings by the Ipswich waterside, a location that suggests that destitution may have pushed her into sex-work.

It was during this period that Margaret committed her first felony. Previously, she had led a respectable life and was highly-regarded by the Cobbolds. Eliza’s son Richard Cobbold later claimed that she had even saved the lives of some of the Cobbold family but as he made up so much of his biography of Margaret we have no way of knowing whether this was true.

Margaret’s crimes

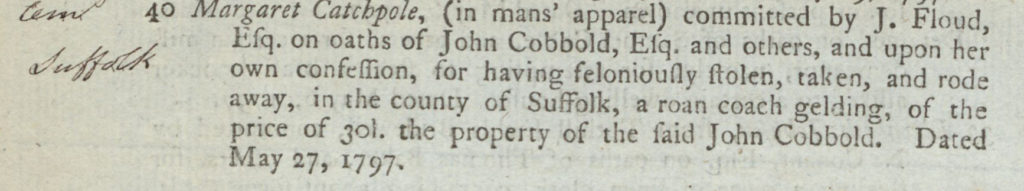

In the early hours of 23 May 1797, Margaret, dressed as a man, broke into John Cobbold’s stables and stole his strawberry roan horse. She saddled up and rode it away, but was seen by the guard of the mail coach riding hard towards London. The following day Cobbold printed up a poster advertising a reward of five pounds for information about the roan and about another horse he had lost earlier.

Margaret initially aimed for Chelmsford in Essex, about 45 miles away, but apparently thought better of it. Despite her disguise, she feared she would be recognised so close to home, and instead decided to keep on for London, arriving at Whitechapel in the east, in the evening. The following morning she tried to sell the horse for thirty guineas (£31.50). The law caught up with her at a horse dealer in Marsden Street, Moorfields. The guard of the mail coach, sent in pursuit of the thief by John Cobbold, had tracked her down and had had her arrested. Everyone was amazed to find that the culprit was a woman.

The Cobbolds set off for London, John to prosecute Margaret for theft, and strange as it might seem, Eliza to support her former servant. The theft of a horse was a felony and all felonies carried the death sentence. Margaret was facing potential death at the gallows and, although only about one in ten sentences were actually carried out, the alternative punishments were severe; transportation to New South Wales was the most usual outcome. “The poor unhappy creature was so affected when she saw me, it was some time before she could enter the room,” wrote Eliza to a stepdaughter.

During the next three hours, Margaret Catchpole confessed her crime and was charged with stealing the horse. She claimed that she was goaded into it by a passing sailor friend called John Cook but his identity has never been proved. She had bought the male attire herself, she said, but it is not clear how she got the money to do so. She never gave a good account of why she had taken the horse, except to say that Cook promised to be a “friend” to her.

Margaret was remanded to Newgate and later transferred to Ipswich Gaol. On 7 August 1797 she was tried in front of Lord Chief Baron McDonald at Bury St Edmunds Summer Assizes, who sentenced her to death, as the law stipulated. Twelve days later she was reprieved, the Cobbolds having spoken up for her, and given transportation for seven years instead. She was returned to Ipswich Gaol, where at least conditions were reasonable – it was one of the first prisons to be run on the principles advocated by the prison reformer John Howard.

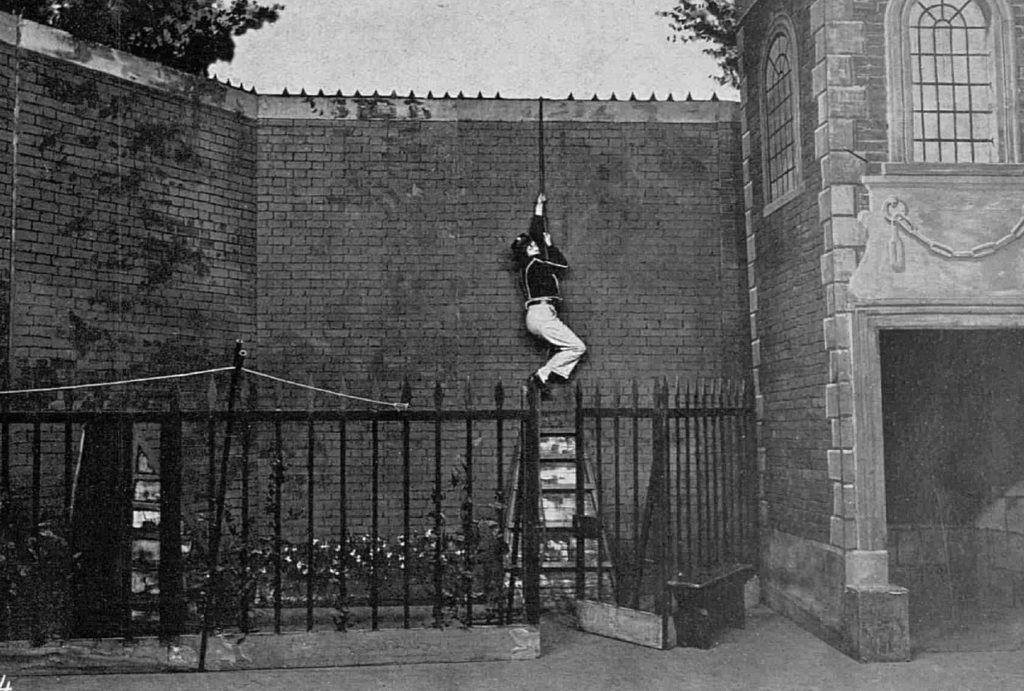

On 23 March 1800, nearly three years after she was tried, Margaret slipped out of the women’s ward at supper time and, dressed in a sailor’s suit (pantaloons and a smock frock) she had sewn herself out of bedsheets, scaled a 20-foot perimeter wall using home-made linen rope. The hand-bill offering a reward for her arrest described her as “very dark, swarthy, and hard favoured.”

It is difficult to understand why Margaret felt the need to escape. Perhaps she feared that after she was finally to be sent to the prison hulks moored in the Thames Estuary and elsewhere. They had a fearsome reputation as pits of disease and brutality, and it was not unknown for prisoners to languish there for years before being selected for transportation. She may have feared the journey to New South Wales itself. Ships captains were known to make profits by withholding supplies of food and bedding, hoping to sell it once they landed, and women could be vulnerable to sexual abuse from the crew and from the male prisoners.

Once she was out, she headed for the home of a friend and then for the nearby marshes, perhaps looking for help from a smuggling gang, but was not at liberty for long – her friend gave up her whereabouts when the prison governor threatened her with imprisonment. Margaret appeared at the Bury assizes two days after her escape and was once again convicted of a capital offence (this time of escaping) and sentenced to death.

There was still no appetite for Margaret’s execution. In early August her sentence was respited and she was given transportation to New South Wales for life. She had been doubly lucky. Her case offers a sharp contrast to the unfortunate Sarah Lloyd, who had appeared at the same Bury assizes a few days before Margaret’s escape and was hanged a month later, despite vociferous objections by Capel Lofft, a barrister, magistrate and MP. Sarah’s crime was allowing her lover Joseph Clarke to enter her mistress’s house after dark to steal money and valuables. When she was caught, Sarah confessed all, but this served only to seal her fate. Clarke confessed nothing and the case against him was dropped for lack of evidence.

Margaret was once more returned to Ipswich Gaol to await transportation. Again she was lucky. Not only did she have a further nine months at Ipswich before she was taken to Portsmouth, but conditions on the ships had improved greatly since her original sentence – the government started paying a bonus for the arrival of healthy convicts and voyages were now segregated between men and women. However, Margaret needed money just to survive and so wrote to Eliza Cobbold the first of a series of letters that are now treasured by the National Archive of Australia.

My sorrowes are very Grat to think I must Be Banished out of my owen Countreay and from all my Dearest frindes for ever… I must humbly Beg on your Goodness to Consider me a Littell trifell of money, it would be a very Grat Comfort to your poor unhappy searvant.

Transportation

On 19 June she and 95 other women spent the first of 176 days aboard The Nile, disembarking in Botany Bay in mid-December 1801. Again, Margaret was lucky. She was chosen to work as a cook to John Palmer, a well-off official, at Woolloomooloo Farm. She wrote to Eliza in January 1802:

As i was a Going to be Landed, on the Left hand of me, it put me in mind of the Cleeff1, Both the housen and Lik wise the hills so as it put me in very Good spirites seing a places so much Lik my owen nativ home. It is a Grat deel moor Lik englent then ever i Did expet to a seen for hear is Gardden stuff of all koind expt gosbres and Currenes and appelles. The Garddens are very Buttefull in ded all planted with geraniums and they run up 7 and 8 feet hy.

For the details of further letters written by Margaret to Eliza Cobbold, who sent boxes of clothes and gifts to her, and to her uncle and aunt, I refer you to Margaret Catchpole: Her Life and Letters by Laurie Chater Forth, available from The Cobbold Family Trust. These letters, the last one written in 1811, have given Margaret a unique place in Australian history as they are among the few written home by convicts (not many of whom were literate) and even fewer by women.

Margaret eventually acquired a small farm of her own. She did not marry, nor did she have children of her own but she worked as a midwife and was highly thought-of. She died of flu in 1819, aged 58, and was buried at Richmond.

Richard Cobbold’s “perfectly true narrative”

And that would have been that. She would have faded from view, but for the imagination of the Rev Richard Cobbold.

In 1845, when Cobbold was 48 and the rector of Wortham in Suffolk, his purported biography Margaret Catchpole, a Suffolk Girl, which he claimed was a “perfectly true narrative”, was launched on the public. In effect, Cobbold had written a historical romance with a theme of Christian redemption (indeed, the final chapter is titled ‘Repentance and Amendment’). According to Cobbold, it was lack of religion that caused Margaret to fall into “errors of temper and passion, which led to the violation of the laws of God and man.” It was only when she discovered the truth of the Christian faith that she was able to return to God. For the story to reach its full potential, however, some of the truth about Margaret’s own life had to be embellished, massaged or magicked away.

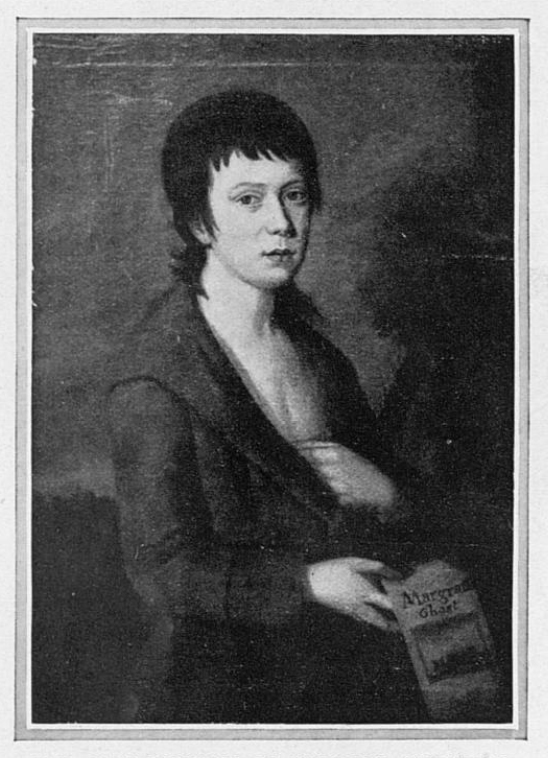

Cobbold, whose ponderous style perfectly reflected his amiable pomposity, decided to render Margaret a more acceptable heroine by making her beautiful, shaving ten years off her age and by providing her with a passionate but chaste affair with a fictitious handsome smuggler, William Laud. According to Cobbold, it was Laud who urged her to borrow the horse and ride to London where they would be married. He was subsequently conveniently killed off in an altercation with a revenue man. In Australia the misunderstood Margaret settled down nicely, married and had children, and died in 1841.

Cobbold also painted 33 charming naïve watercolours illustrating the dramatic points in Margaret’s life.2

The book was a roaring success and spawned numerous plays, musicals and, in the 20th century, films and an opera.3. The legend of Margaret Catchpole persists even into the 21st century, with Carol Birch’s novel Scapegallows published in 2007, based not on Margaret’s life but on Richard Cobbold’s version of it.

Cobbold’s fictions were bold. In 1845 Margaret was still part of living memory and there were plenty of people in England who knew her who were still alive. Cobbold claimed to have inherited “documents” relating to Catchpole but did not, perhaps could not, produce them. His mother, from whom he claimed he learned about Margaret’s early life, died in 1824 and was no longer available to offer her perspective.

Still, we should be grateful to Cobbold for keeping the idea of Margaret Catchpole alive. She would probably not be known to us but for his novelisation. She was clearly a much-loved, intelligent, capable and creative person who was kept back by lack of education and opportunity. I like to think that life in Australia allowed her to achieve at least some of her potential.

- A reference to the Cobbold’s home at the Cliff Brewery

- Richard Cobbold & Pip Wright (2015), A Picture History of Margaret Catchpole. Pawprint Publishing. Available from the Cobbold Family Trust.

- A small selection – Edward Stirling (18??), Margaret Catchpole: The Heroine of Suffolk or The Vicissitudes of Real Life. London: Thomas Hailes Lacy. The Romantic Story of Margaret Catchpole, film, starring Lottie Lyell and Augustus Neville, Dir. Raymond Longford (1911). Ipswich Arts, Margaret Catchpole (1970), a musical by members of the company (The Stage, 29 Oct 1970, 1C).

Thank you Naomi, for this account of my Ipswich hometown girl. Your perspective, completely different to that learnt in my school years, has encouraged me to research more.

My pleasure, Nicholas. The book by Laurie Chater Forth is not how I would have written her life but it is very informative, especially the research on Margaret’s origins. Do let me know if your research turns up any nuggets! All the best – Naomi

Have just read the book by Rev Cobbold have been to Nacton to try and see her mother grave but no luck would like to see her grave in Australia if it is there

Thank you for this. I have just written a poem about Margaret Catchpole. It includes her affair with William Laud so I’m a bit disappointed to hear that it’s probably fictitious.

Either way she’s an absolutely fascinating character.

I’m glad that she’s inspired so much interest.

Mai Black x

Ha! Just found this ad I’m trying to get into character to play the ghost of Margaret Catchpole – thanks for writing both this blog and to Mai for the poem.