On 2 December 1816, Taunton solicitor Henry James Leigh wrote to his wife Anne Whitmarsh Waters from the New Hummums, the Covent Garden hotel where he habitually lodged when his business took him to London. He was up in town with his client George Lowman Tuckett.1

Leigh reassured his wife that he had received the parcel she sent. He was much relieved that her latest letter included news about the improvement in the health of one of their children. The main point of the letter, however, was to make Anne “perfectly easy” on the subject of his safety in London, which was currently on tenterhooks after serious disturbances in the city and an attempt by the mob to gain access to the Royal Exchange. “Depend upon it,” he wrote, “if there be a riot in the East, I shall be found in the West, so vice versa.”

Seventeen days before Leigh wrote his letter, on Friday 15 November, a huge rally was held in Spa Fields, then a large open area near Clerkenwell. The mood amongst the demonstrators was of seething discontent. 2 The city was awash with redundant soldiers and sailors, their services no longer required now that the war with Napoleon was over. The labouring classes were often on the brink of ruin and starvation but conditions seemed worse than ever: the cost of everyday commodities had soared, the result of the poor harvest (this was the Year Without a Summer3) and the Corn Laws, which inflated prices to reward the already-wealthy. Not only that, the Prince Regent, who was supposed to have a paternal care over his people, seemed to almost thumb his nose at his subjects with his extravagant spending. As Andrew Knapp and William Baldwin, the authors of The Newgate Calendar, put it, 1816 was ‘a moment of paramount distress.’

There is huge variation in accounts of the sequence of events at Spa Fields on 15 November and the reasons for its terrible ending. According to Knapp and Baldwin, the Radical organisers behind this first Spa Fields gathering, in November, cynically took advantage of discontent amongst the poor and whipped up their feelings. They included several men who had been inspired by the philosophy of Thomas Spence, the leader of the Spencean Philanthropists, whose aims included the establishment of a republic, the end of aristocracy and landlords, and common ownership of all land (each family was to have seven acres), votes for all (and, unusually for the time, that included women) and an end to child labour. Spence died in 1814 but Arthur Thistlewood, James Watson and Thomas Preston continued to promote his ideals and, deciding that the time was right for revolution, called a public meeting at Spa Fields. In order to get a large crowd Thistlewood invited two of the best known speakers of the day, William Cobbett and Henry (‘Orator’) Hunt. Cobbett refused but Hunt, who did not support violent revolt, eventually agreed.

Ten thousand people were in Spa Fields when Hunt, wearing his trademark white top hat, spoke first from the roof of a coach and then from the upstairs window of The Merlin’s Cave pub about the poverty of British workers and how taxation to pay for the army’s occupation of France and to police British people was the cause of their misery. A petition was drawn up demanding the Prince Regent provide relief for the poor and put together proposals for parliamentary reform including universal male suffrage, annual general elections and a secret ballot. This meeting broke up without incident but when Hunt attempted to deliver the petition he was refused three times.

Amid an atmosphere of growing tension, another meeting at Spa Fields was called for 2 December. On that day, the crowd entered Spa Fields bearing two tricoloured flags and a white banner. One of the flags bore the words “Nature, Truth and Justice! Feed the hungry! Protect the oppressed! Punish crimes!”4 and the banner “The brave soldiers are our brothers; treat them kindly.” By the time James Watson addressed the crowd, while standing on a waggon, the crowd had reached about twenty thousand.

“I am sorry to tell you,” said James Watson, an apothecary who went under the title “Dr”,5 “our application to the Prince has failed… Is this man the Father of the People? No! Has he listened to your petition? No. The day is come!”

“It is! It is!” responded the crowd.

“We must do more than words,” exhorted Watson, continuing the attack on the Regent, “a man who receives one million a year public money, [who] gives only £5,000 to the poor”. The starving had been abandoned, he said, robbed of everything. Four million people were in a distressed condition and “our brothers” in Ireland were in a worse state.

Watson likened the Tower of London to the Bastille and called for the mob to follow him there. While most of the crowd waited in Spa Fields for Hunt, who had been deliberately waylaid in Cheapside by a man called John Castle, some followed Thistlewood. (His attempt to persuade the soldiers guarding the Tower to lay down their arms was unsuccessful.) Meanwhile, a breakaway group, fired up with righteous anger, moved off from Spa Fields in the direction of Clerkenwell to confront the Mayor at Mansion House.

But if the revolution had started, they needed guns.

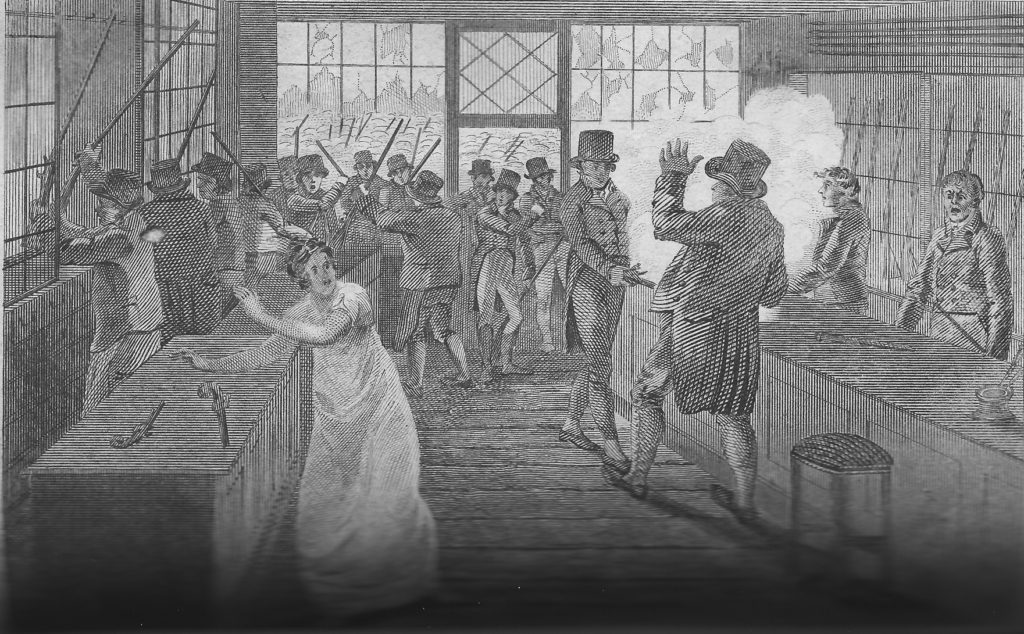

A few hundred metres from Spa Fields, at 58 Skinner Street, the premises of the gunsmith Andrew Beckwith, Mr Platt was discussing a repair to his gun with John Roberts, Beckwith’s shop assistant, when a young man came in shouting and waving a pistol about.

“Arms! Arms! I want arms!”

“My friend, you are mistaken; this is not the place for arms,” said Platt, perhaps drawing a distinction between arms for defence and those for offence. The young man promptly shot Platt in the stomach and pistol-whipped him. The shop assistant sprang into action and disarmed the shooter, hauling him off to the back room and locking him in. The constable who arrived was not so careful and naively allowed the shooter to go upstairs, where he opened the window and called on the mob to rescue him. They promptly retrieved their comrade, broke the shop windows and stole guns and pistols while they were at it.

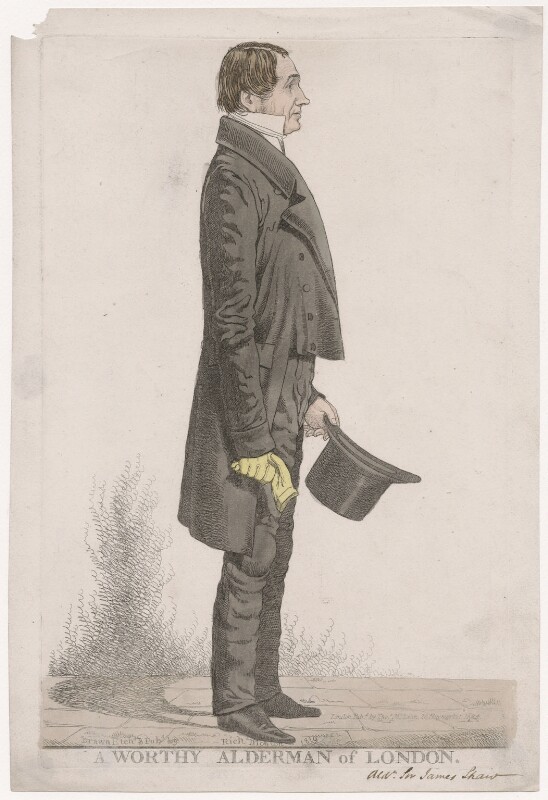

The rest of the mob, meanwhile, were heading down to Cheapside, firing guns as they went, towards the Bank of England. At the Royal Exchange they tried to force the gates and fired at the Lord Mayor, Alderman Sir James Shaw, and his contingent of policemen. They moved off and broke into two other gun shops where they stole firearms, plate and two field pieces on wheels.

That evening Henry James Leigh was due to dine with “George Greville”6 and set out from his hotel. As he told Anne, “As soon as I heard of the attack upon Beckwith’s the Gunsmith’s shop, from whence some arms were stolen, I walked forwards from Snow Hill and finding the report true, immediately resolved not to dine at any risk. I shall therefore keep my quarters here with Mr T.7 till all is quiet again. The shops in Holborn entirely shut up and as there is a great force of troops and constables in all directions. I doubt not all will be quiet ‘ere the morrow. These are the blasted effects of Citizen Hunt’s Meeting in Spa Fields today. Rely on my prudence that I am not in the smallest danger.”

London’s prisons went into lock-down, soldiers on horseback and on foot patrolled the streets, East India House and the Bank reinforced their security, the gates of the Inns of Court were closed and, as Leigh observed, many of the shops shut. Volunteer special constables were sworn in.

Other rioters headed in the direction of the Strand, where they raided the clothing shops. A contingent went over Westminster Bridge to south London and were followed by the militia to St George’s Fields south of Waterloo where they gradually melted away.

The revolution had become a damp squib. Thistlewood, Watson and Preston had misjudged the moment. Naturally, there were arrests and show trials. At the Old Bailey in March the following year, five men were tried on a charge of theft but only one of them, John Cashman, a 28-year-old Irish sailor who said he had come to London to claim his pay and prize money, was positively identified and found guilty.8

On 12 March 1817, the day of the funeral of Princess Charlotte, he was hanged outside Mr Beckwith’s shop in Skinner Street, the scene of his supposed crime, the New Drop apparatus having been dragged there from Newgate. It was a special pre-mortem punishment, involving a humiliating journey by cart to Clerkenwell. Beckwith, understandably, objected to the erection of a gallows outside his business premises and had tried in vain to get the hanging moved back to Newgate. It probably did not add to his peace of mind that from the platform, Cashman threatened to haunt his house.

Thistlewood, Watson and Preston were arrested and tried but they were all acquitted after it was proved that John Castle, who had delayed Hunt on his journey to the demonstration, was an agent provocateur working for the government.9

FlickeringLamps has an excellent piece on Spa Fields itself.

- Tuckett was a barrister who had had a promising career in the West Indies but who returned to England when his wife became ill. He played a prominent part investigating the crime at the heart of my book The Disappearance of Maria Glenn.

- Spa Fields was used as a pleasure garden in the 18th century but from 1787 it was a burial ground for the poor. Now much reduced in size, Spa Fields is a park.

- Worldwide disruption to the climate as the result of the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815.

- Taunton Courier, 5 December 1816, 8A.

- This account is from the Whig-leaning Taunton Courier. Accounts of the order of events and their nature vary.

- Possibly George Granville (b. 1792), the barrister and later MP for Oxfordshire.

- George Lowman Tuckett.

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2, 16 January 2018), January 1817, trial of JOHN CASHMAN JOHN HOOPER RICHARD GAMBLE WILLIAM GUNNELL JOHN CARPENTER (t18170115-64).

- In 1819 Hunt addressed the crowd before the Peterloo Massacre. Thistlewood was hanged in 1820 for his part in the Cato Street Conspiracy to murder the Prime Minister and the cabinet.

Dear Naomi,

Your account of the state of the country and the Spa Fields Riots is fascinating. I am interested in the events because an ancestor of mine had lodged two fowling pistols at Beckwith’s shop, most likely at the beginning of 1817 when he was visiting England from Newfoundland. Do the shop’s records still exist. Also may I download and use the illustration of the raid of Beckwith’ shop in a family history I am writing.

Thank you and best wishes,

Cecile

Hi Naomi

I read with interest the account of the Spafields riots especially as I own a gun by Henry Beckwith, son of William Beckwith, 58, Skinner Street.

Would you possibly know if the records of the business still exist. Was Beckwith bought out by another gunmaker . Fascinating reading.

Regards

Dave Upton

I don’t have any specific knowledge, Dave but I found this at https://www.archivingindustry.com/Gunsandgunmakers/directory-b.pdf

Beckwith Henry Beckwith. A gunsmith listed at 33 Fieldgate Street in 1858–65, and 58 Skinner Street, London E., from 1864 until 1868.

Beckwith William A. Beckwith. The name of this English gunsmith has been linked with firearms, apparently including an occasional self cocking pepperbox, made in the 1860s. Indeed, H.J. Blanch, writing in Arms & Explosives in 1909, lists Beckwith at a variety of London addresses in the mid nineteenth century, culminating at 58 Skinner Street, London E., as late as 1868. However, William Beckwith had died in 1841; the business was continued in his name by widow Elizabeth and son Henry.

Land Tax records show Elizabeth Beckwith living at 52 Snowhill in 1849. The 1851 census lists her at 58 Skinner Street, described as a Gunmaker Employer , living with Henry Beckwith (born approx 1804), described as Foreman Gunmaker.

There is some information on Henry here: https://collegehillarsenal.com/3rd-Model-Tranter-54-Bore-Revolver-by-Henry-Beckwith

Henry died, unmarried, in 1877, leaving effects worth under £200.

Hope this is of interest

Naomi