At about noon on Monday 27 April 1812, 28,000 inhabitants of St Vincent, free and enslaved, witnessed the sudden and violent start of the eruption of La Soufrière (The Sulfurer), the huge volcano in the north of their tiny Caribbean island. As great thunderous cracks split the air, the earth shook, a massive column of thick black smoke rose from the summit and volumes of red-hot sparks were spat into the atmosphere. Birds fell dead out of the sky. Everyone on the island, whether enslaved or free, was terrified.

“In the afternoon the roaring of the mountain increased and at seven o’clock the flames burst forth, and the dreadful eruption began,” wrote barrister and plantation owner Hugh P. Keane. The volcano was not just a thing of terror — it was also sublimely beautiful, and three days after the volcano first stirred, Keane rose early to sketch the scene, with the volcano’s sulfurous vapours curling skyward and the air filled with layers of yellows, reds and rusts. His drawing, now lost, somehow made its way to an acquaintance, the artist J. M. W. Turner, who used it as inspiration for a work he showed at the Royal Academy in 1815. Turner’s painting is now in the collection of the University of Liverpool.

Lava boiled up over the edge of La Soufrière until there was a massive explosion from the north-west side of the mountain and a molten river snaked its way through the sharp hills pushing its way to the west coast and pouring into the sea. Another vast stream spread eastward. Then the first earthquakes were felt, followed by showers of cinders, stones and red-hot magma. It was as if the earth were in a state of continuous movement, undulating like water shaken in a bowl.

The next morning, the island was in total darkness, as though the sun had failed to rise. A thick haze hung over the sea and the sky filled with yellowish black clouds. The island was covered with ash, cinders and fragments of lava—and the volcano was still rumbling. Gradually it settled back into silence.1

In all, about 80 people died, relatively few for an eruption of such force, although there were many injuries, particularly amongst the slaves working in the fields. Two of the rivers had been completely dried up. The crops were ruined, and food had to be bought in from neighbouring islands.

Unknown to the inhabitants of St Vincent, the eruption of La Soufrière was only one episode in a wave of huge seismic and tectonic disturbance stretching from one side of the world to the other. In December 1811 the Mississippi River valley had been convulsed by an earthquake so severe that it woke sleepers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Norfolk, Virginia. It was followed by intermittent strong shaking which lasted until March 1812 and the aftershocks continued for five years.2 Only 35 days before La Soufrière erupted, the city of Caracas in Venezuela had been almost completely flattened by two huge seismic shocks. Ten, possibly twenty, thousand people died. And there was worse to come. In Indonesia, Mount Tambora began to stir and rumble and a dark cloud appeared over its summit.

Three years later, on 5 April 1815, Tambora spewed thousands of tonnes of volcanic ash, gas and dust into the upper atmosphere. The island was nearly sheared in half, a tsunami ripped the coastlines and for days the area was covered in darkness. The ash clouds and sulphur aerosols from the eruption, estimated as six times that of Mount Pinatubo in 1991, chilled the climate by blocking sunlight with gases and particles. The human cost was enormous. Ten thousand people were killed during the eruption, probably by pyroclastic flows, and a further 38,000 died from starvation on Sumbawa and 10,000 on Lombok.3

The effects were felt worldwide. Spectacular sunsets in which the horizon glowed red and yellow with purple or pink were seen in England. J.M.W. Turner, who had unveiled his painting of the eruption of La Soufrière at the Royal Academy in 1815, captured some of them in his vivid and unusual paintings.

The weather changes, which were more evident the following year, brought widespread suffering and death. By spring 1816 a persistent dry fog, which reddened and dimmed the sun, was affecting north-eastern America. In Albany in New York State snow fell in June and did not melt, and in July and August there was lake and river ice as far south as Pennsylvania. Parts of Ireland suffered near famine conditions. Typhus swept through the country.

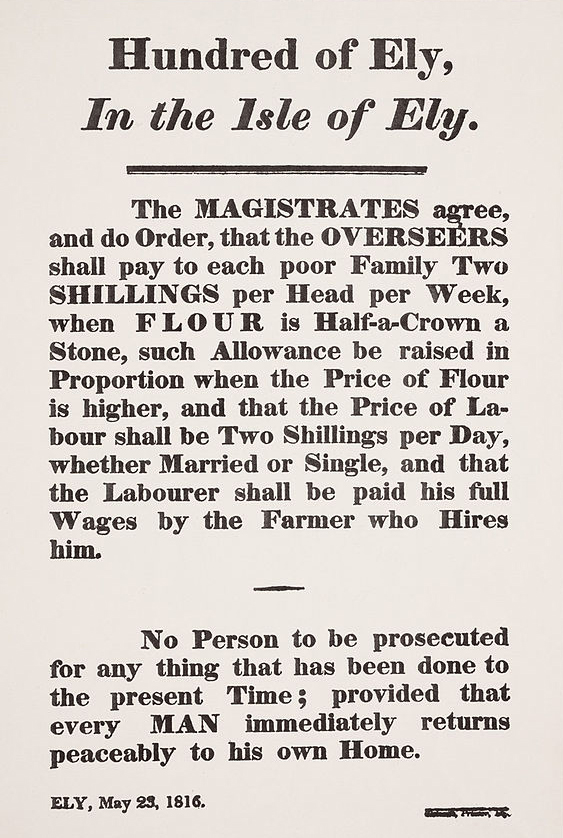

In England crops failed and there were violent protests in grain markets. In May 1816, riots broke out in Norfolk, Suffolk, Huntingdon and Cambridge. Threshing machines, barns and grain sheds were destroyed. Groups of rioters armed with heavy sticks studded with iron spikes and carrying flags proclaiming “Bread or Blood” roamed the countryside. The disturbances were only quelled when the Riot Act was read and the death penalty threatened.4

In August 1816, the Taunton Courier bemoaned the unfortunate state of the wheat crop, which had been badly afflicted with canker. Whether or not this was the result of the recent “incessant rains” the paper could not say, but it predicted a sharp rise in the price of wheat and the need to import supplies. The piece finished with a heartfelt plea –“God help the farmers!”5

In August 1816, the Taunton Courier bemoaned the unfortunate state of the wheat crop, which had been badly afflicted with canker. Whether or not this was the result of the recent “incessant rains” the paper could not say, but it predicted a sharp rise in the price of wheat and the need to import supplies. The piece finished with a heartfelt plea –“God help the farmers!”5

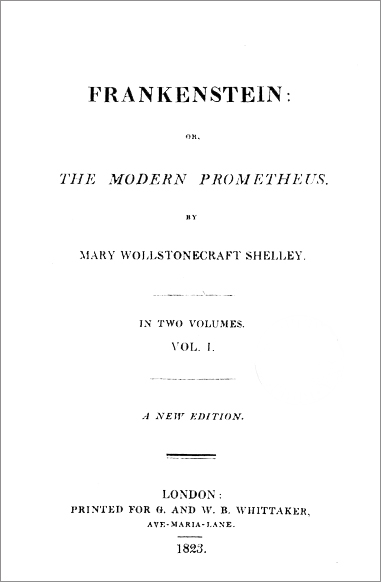

In Switzerland the continuous summer rainfall forced Mary Shelley, John William Polidori, Lord Byron and their friends to stay indoors, where they competed to write scary stories. Shelley came up with Frankenstein and Byron with the bones of a story Polidori later used as the basis for his story The Vampyre, a precursor to Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

1816 came to be known as the Poverty Year or the Year Without a Summer.

1816 came to be known as the Poverty Year or the Year Without a Summer.

- History of the West Indies (Vol 5), R. Montgomery Martin. London, Gilbert and Rivington, 1838. This account appears to rely on the uncredited diaries of Hugh P. Keane, now in the collection of the Virginia Historical Society.

- Earthquake Information Bulletin, Volume 6, Number 2, March – April 1974, by Otto W. Nuttli.

- Figures quoted by Clive Oppenheimer, Climatic, environmental and human consequences of the largest known historic eruption: Tambora volcano (Indonesia) 1815. Progress in Physical Geography 27,2 (2003) pp. 230–259.

- Read The Observer‘s account of the riots in Norfolk, Suffolk and Ely (the Littleport riots).

- Taunton Courier, 1 August 1816. “The Approaching Harvest”.

Leave a Reply