86 Wimpole Street, London

13 February 1818

At two o’clock in the morning in a house belonging to his sister-in-law, Dr Thackeray, a chaplain to the King, hears an unusual noise, like the overturning of a chair. He thinks nothing of it and goes back to sleep. An hour later, a maid knocks at his door and tells him that, at last, his wife will soon deliver the long-awaited child. He immediately goes to wake the doctor, Sir Richard Croft, who is taking some much-needed rest. Croft has been up for days attending to Mrs Thackeray’s wife, whose labour has been arduous and protracted. Thackeray had seen that the doctor was exhausted and insisted that he snatch some sleep.

He finds the doctor on the bed, a pistol in each hand, his head “literally blown to pieces.”

Someone notices later that on a chair nearby, a copy of Shakespeare’s Plays lies open at a page of Love’s Labours Lost that includes the line “Good God! Where’s the Princess?”1

* * *

Three months earlier, Croft had been in charge when the 21-year-old Princess Charlotte gave birth. Her labour, which was difficult and dangerous, lasted two days. The baby was lying transverse and was stuck but Croft was reluctant to use forceps and a caesarian would have meant the death of the Princess. Obstetrician Sir John Sims was sent for but Croft refused to allow him to see the Princess in person. Eventually, the baby, a fine nine-pound boy, was stillborn, and after initially appearing to rally the Princess also died.2

The nation was plunged into mourning – Charlotte was almost universally popular – and her father, the Prince Regent, was so prostrated with grief that he could not attend the funeral. Croft was distraught, despite assurances from the Regent and the Princess’s widower, Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saafeld,3 that they did not hold him responsible and fully accepted that he had done his best. Even after an autopsy concluded that nothing more could have been done, Croft was weighed down with depression and guilt.

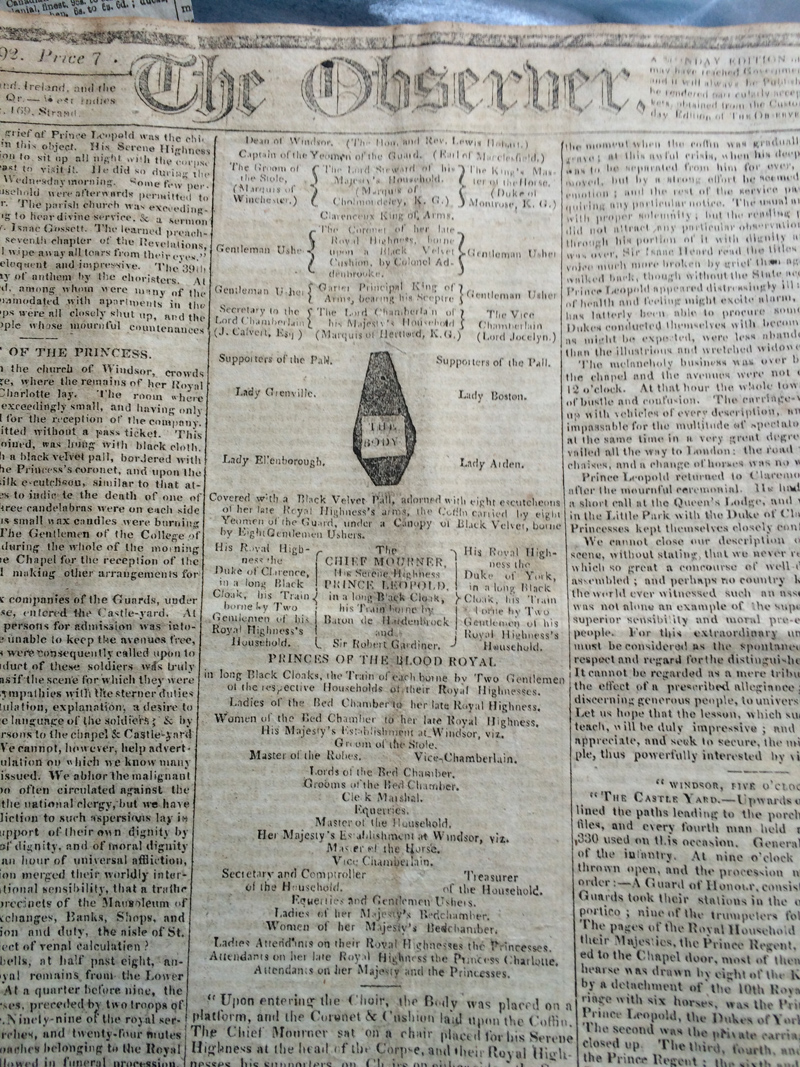

Funeral of Princess Charlotte: Front page of The Observer, 23 November 1817 showing part of the procession to the chapel

Three months later, while at Wimpole Street, when Mrs Thackeray’s family expressed anxiety about the length of time her labour was taking, he said: “If you are anxious, what must I be?”

That night Croft lurched between calm and panic but he was careful always to appear in control when he was with Mrs Thackeray herself. Her husband, meanwhile, grew alarmed at the doctor’s state of mind and his obvious tiredness and urged him to take some rest. Unfortunately, Croft was given a bedroom which contained a pair of loaded pistols, kept by Thackeray to “guard against midnight predators”.

Nearly twenty hours after Croft died, at eight in the evening, Mr Stirling, the Westminster Coroner, held an inquest in a room of the house. Mr Thackeray, the maidservant and some of Croft’s medical colleagues appeared and testified to the events of the night and to Croft’s mood. The jury was of the opinion that Croft “Died by his own act, being at the time he committed it, in a state of mental derangement” and by ten o’clock his body was on its way to his own home in Old Burlington Street.4

* * *

Two hours after Sir Richard Croft ended his life, his patient, who had not been told of the fatal events in the house, gave birth to a healthy child.

Perhaps you’s also like to read my detailed account here:

https://prinnystaylor.wordpress.com/2011/09/02/the-tragic-death-of-sir-richard-croft/

Thanks for that Charles. What an awful chain of events.