Early in the morning of Tuesday 27 May 1817, a labourer came across a pair of boots, a bonnet and bundle of clothes near a stagnant pit of water just north of the village of Erdington near Birmingham. He surmised that someone had gone into the pit and ran to raise the alarm at a nearby wiredrawing factory. Among the workers who hauled out the body of Mary Ashford, a 21-year-old farm servant, were two men, Joseph Bird and William Lavell, who conducted a minute examination of footprints in a nearby field and tracks and pools of blood near the pit, and from these clues constructed a timeline of the events leading to the poor girl’s death. William Lavell knew Mary personally; initially her body was taken to his cottage, where his wife Fanny was given the task of undressing and washing it in preparation for the Birmingham doctors who would perform the autopsy. Within a few hours of the discovery of Mary’s body, Abraham Thornton, a bricklayer living near Castle Bromwich, was interviewed and charged with Mary’s murder.

Mary’s death and the subsequent sensational acquittal of Thornton at a trial in August led to an avalanche of comment, newspaper column inches, plays and pamphlets. It was all anyone could talk about. Among the many artefacts published both before and after the trial were explanatory maps showing the topography of the crime. Thornton’s trial defence relied exclusively on alibi evidence – he claimed he was miles away when Mary was being attacked – and two maps were displayed in the courtroom, one each drawn up for the prosecution and the defence. The best of the maps sold to the public was made by 23-year-old Rowland Hill (who went on to find worldwide fame as the founder of the penny post), who felt that the crude representation of the map printed in a local newspaper using glyphs and punctuation marks, was inadequate. I have written about Hill’s map in a previous post.

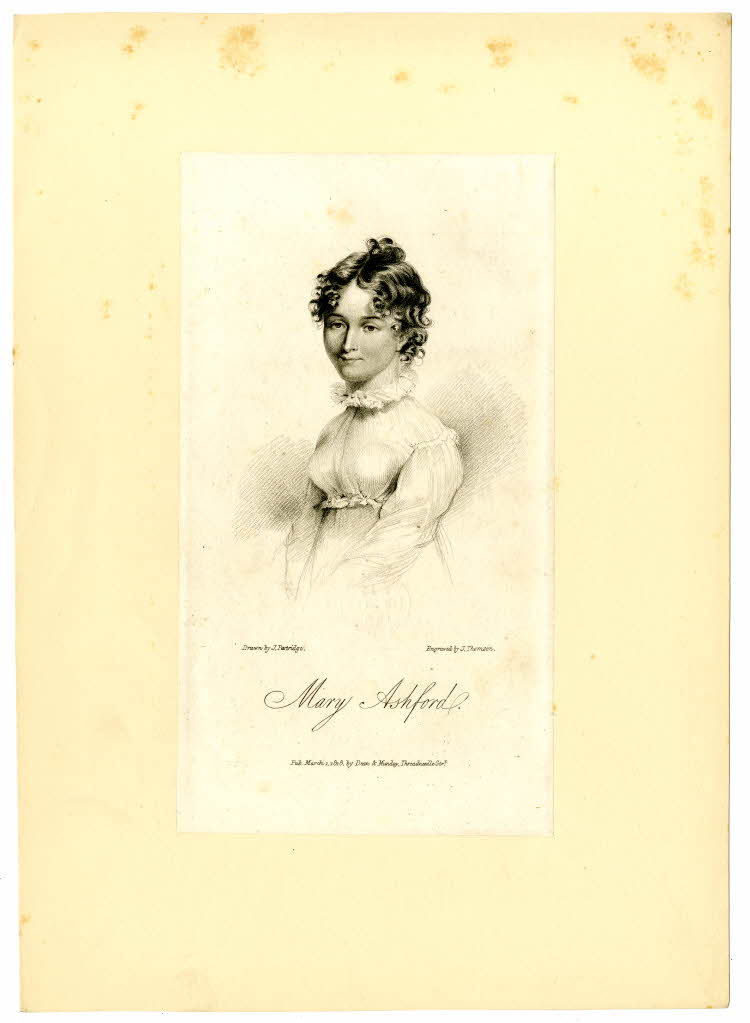

There were also many prints portraying Mary, most deriving from a portrait created by the famous Birmingham artist and teacher Samuel Lines and published in December 1817, seven months after the crime. Lines’s portrait shows Mary dressed in a spencer and white dress with a ruffed neck and a close fitting bonnet decorated with a ribbon, carrying a trug filled with eggs from her uncle’s farm at Langley Green. Among her duties was to walk into Birmingham every Monday, a distance of about seven miles, to sell them at the market, and this she had done the day before she was killed. She had a regular spot near the Castle Inn.

Lines shows Mary gazing out, not quite directly at the viewer, a hint of her fate in her eyes, her lips together in a sweetheart bow. Her sharp, fine facial features imply her dainty frame and hence her vulnerability. Although she looks wistful and pensive, she looks confident, happily occupying her space. In life she was known for her friendliness and for the speed at which she walked.

At the time this print went on sale, a fight-back against the verdict was underway, with the supporters of Mary’s family investigating a second prosecution using a little-known medieval law to force Thornton back to court. Was this finely etched portrait commissioned as part of the campaign? What do we know about it? How accurate a representation of Mary was it?

There is not much to go on and in the absence of documentary evidence, I will have to rely on other, less tangible, clues.

One of the fragments of information about it is this. Several decades after the murder, Rowland Hill, who was taught by Samuel Lines at Hilltop school, wrote:1

My drawing-master [Samuel Lines] published a portrait of the poor girl – taken, I suppose, after death – with a view of the pond in which the body was found.

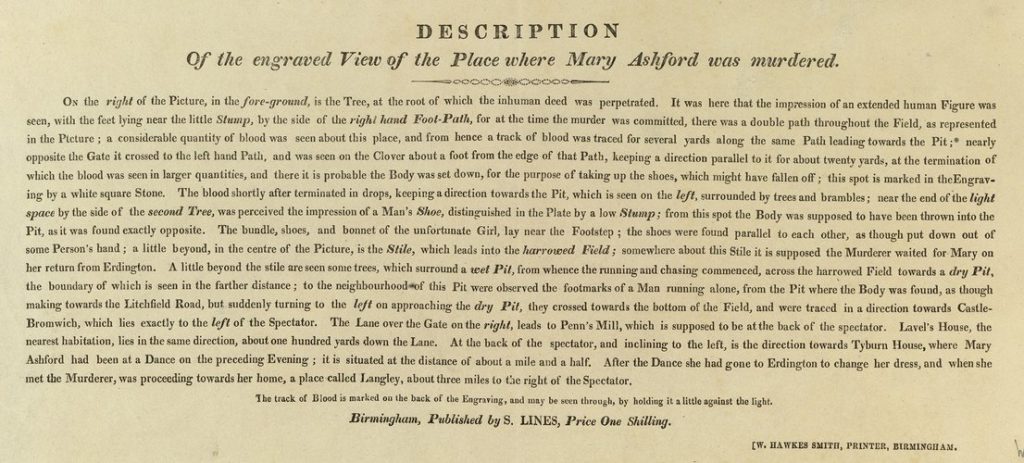

Nothing I have seen in the archives corroborates Hill’s supposition that Lines visited Mary’s body, which does not prove that it did not happen. However, we can be fairly sure that Lines visited the scene of the crime. Lines published ‘View of the Place Where Mary Ashford Was Murder’d’ in November 1817, a month before the portrait went on sale.

With his map of the murder Hill included a long caption, and Lines included a similar paragraph with his ‘View’. In this he gave the probable order of events and pointed out the important locations in the crime: where Mary was raped, the impressions in the grass, the spot where her possessions were found. There was also an additional aid to understanding the crime. The track of blood from Mary’s body was marked on the back of the print and could be ‘seen through, by holding it a little against the light’). To our 21st century sensitivities this is a rather grisly touch but in 1817 this would have been seen as information helpful to a public emotionally invested in understanding the evidence. Across the region, and indeed the country, people felt outraged that Thornton seemed so far to have escaped justice.

How can I be sure that Lines actually visited the scene in order to produce his ‘View’? There are three aspects that point in that direction. First, the level of detail. The ‘furniture’ in the scene – the gates, the trees and their canopies, the reeds by the pond – has been minutely, lovingly even, rendered. This gives the drawing a freshness, an immediacy and, to me at least, suggests that Lines sat there in the sunshine with his sketchbook and pencils.

Compare the style of the ‘View’ with an illustration Lines made seven years later for the Female Society for Birmingham, the foremost female abolitionist group in Britain, showing an enslaved woman and her child behind harassed by an overseer. The design was printed on silk satin and made into a sewing bag.2 Given the medium and the process of transferring the design, it is no surprise that the printing is cruder than that of the ‘View’. Even so, the drawing has an utterly different feel to it. Lines did not travel to the West Indies to sketch the scene; he would have used secondary sources as references for the palm trees and the landscape behind. The result is that everything is reduced, flatter, almost two-dimensional. The human figures are also caricatures, with the plants and landscape used as design devices. It has every appearance of having been ‘made up’.

The second aspect of the ‘View’ that points to Lines drawing it from life is his reputation in Birmingham. In 1817, he was 39 and an accomplished and fêted landscape painter of scenes in the Midlands and North Wales. Ten years previously he established his own drawing academy in Newhall Street in central Birmingham and later co-founded the Life Academy with other notable Birmingham artists. His aim was to have an institution in Birmingham to match the Royal Academy in London. He would not have consciously harmed his standing by putting his name to a landscape he had not visited in person, especially one that was of such importance to the people of Birmingham.

Finally, there is the significance of that long caption. Lines may have visited William and Fanny Lavell in their cottage and walked with William 100 yards down the path to talk about the case and make the preliminary sketches for the ‘View’. Lavell, who with Joseph Bird had pieced together the narrative of what had happened to Mary and to whose cottage her body was first taken, also spoke to an anonymous contributor to the Lichfield Mercury (possibly James Amphlett, the editor, himself) who found him leaning on the gate to the footpath. He was used to walking people through the events and, as a friend of Mary and her family, was keen to help anyone who would help bring Thornton to justice.

For these reasons I am confident that Lines drew the ‘View’ from life. Of course we cannot know when Lines visited the scene. It could have been within days of the crime – after all, news travelled fast – but did Lines really visit Mary’s dead body in order to make his portrait of her, as Rowland Hill supposed? At the very least it is a possibility, but is it a probability? Lines would have had to have made this visit on Tuesday, the day her body was discovered, or the next day. On Thursday it was autopsied by two doctors, after which his chance was gone. Would it not have been more likely that Lines drew Mary because he knew her?

In an obituary of Samuel Lines, who died aged 86 in 1863, The Birmingham Daily Gazette remarked on his ability to ‘make friends of all with whom he came into contact’.3 It does not stretch the imagination to see him buying eggs from Mary Ashford as she stood at her regular spot, only a ten-minute walk from the Drawing Academy, and making conversation with her. He may have needed eggs to mix tempera for his students.

Lines was one of the world’s natural teachers. He was devoted to his students who, unusually for the time, included women. In a letter to the Birmingham Daily Post, Edward Whitfield, who joined the academy in 1817, remembered his ‘great energy, perseverance and industry’ in encouraging his students. ‘He was indeed a truly honest, upright and conscientious man,’ he added.4

He himself had known adversity as a young person. His mother, the headmistress of a girls’ boarding school in Allesley, near Coventry, died when he was nine; his father, of unknown occupation and for unknown reasons, was unable to care for him and his three siblings. They lived instead with a maternal uncle. Lines showed artistic ability as a young child and was apprenticed in his early teens to an enameller of clock faces in Birmingham, went on to work for a japanner of furniture and by his early twenties was designing sword blades. He was by no means a gentleman artist; he made his own way in life using his artistic talent and remarkable ‘people skills’.

To return to Lines’s portrait of Mary: it was copied and adapted many times. Above is a version, clearly based on Lines, published in John Cooper’s 1818 account of Thornton’s trial and its aftermath.5 Mary looks more directly at us than in Lines’s original but she is flatter, more iconographic, less real. A corresponding portrait of Abraham Thornton, taken from a sketch drawn in court and published in The Observer, by contrast, although hastily produced, has a strongly vital quality.

There is another portrait of Mary that we can be fairly sure was not drawn from life. This shows a prettier, softer woman than Lines gave us, although it was surely based on his portrait. In this version, Mary is without her bonnet and spencer, although she wears the same white ruffed dress. Her hands are clasped demurely in front of her. She simpers wanly. She looks childlike, pliant and powerless. She has none of Lines’s Mary’s confidence.

Portraying Mary as a defenceless victim was part of the campaign against Thornton, her supposed attacker, but it also served to bolster the egos of the men who set out to act as her champions. There was another side to their chivalry: to keep women, their women, at home and without agency. This is a theme I explore in my book about the case, The Murder of Mary Ashford.

In that book I suggest that none of the portraits of Mary were authentic. At the time I wrote it, I did not specifically consider whether Samuel Lines may have come across Mary at Birmingham Market, nor whether he visited the scene of her death. And although we are firmly in ‘best guess’ territory here, my revised opinion is that he probably did know her – from Birmingham Market rather than from seeing her corpse at Lavell’s cottage. 6

- Sir Rowland Hill and George Birkbeck Hill (1880). The Life of Sir Rowland Hill and the History of Penny Postage. London: Thomas De La Rue & Co, p. 85.

- The bags were produced as marketing merchandise for the abolitionist cause and recipients included King George IV, Princess Victoria and other aristocrats and wives of prominent politicians.

- 23 Nov 1863.

- 3 Dec 1863.

- John Cooper (1818). A Report of the Proceedings Against Abraham Thornton at Warwick Summer Assizes, 1817[…]. Warwick: Heathcote and Foden.

- I would like to acknowledge the scholarship of Connie Wan, whose 2012 PhD thesis Samuel Lines and Sons: Rediscovering Birmingham’s Artistic Dynasty 1794-1898 Through Works on Paper at The Royal Birmingham Society of Artists for the University of Birmingham was helpful in writing this post.

Leave a Reply