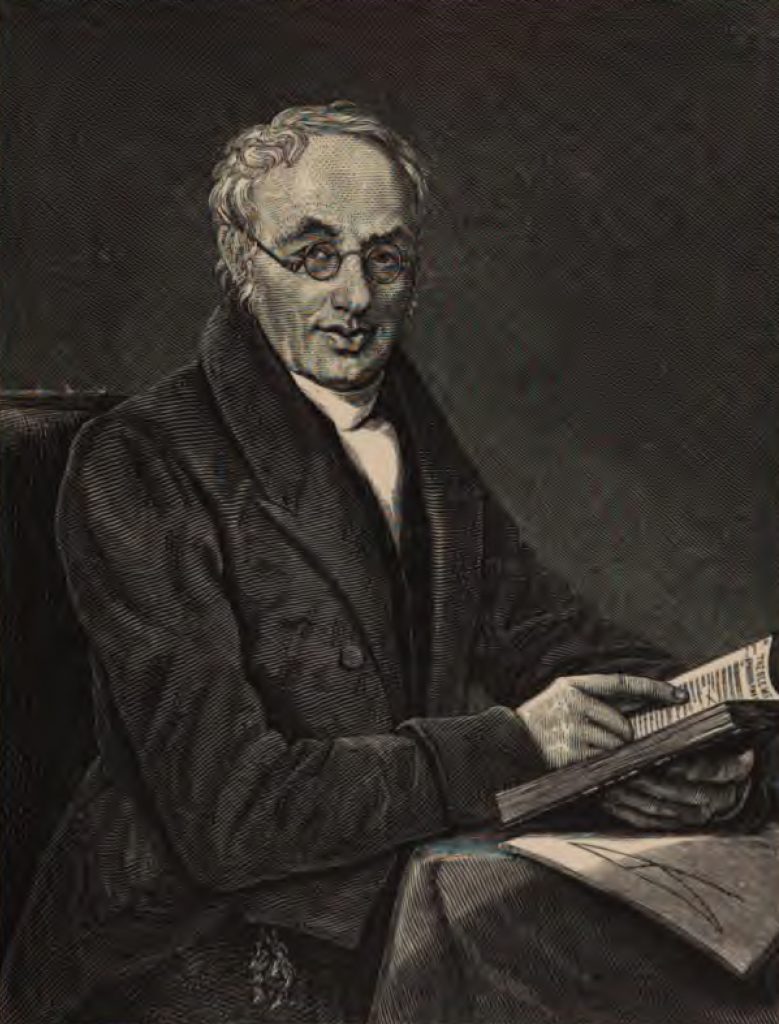

The polymath Rowland Hill is best known for ‘inventing’ the penny post, but his many other talents included art, mathematics and pedagogy.

Rowland Hill’s 1837 Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability resulted in the creation of the revolutionary penny post, by which a letter weighing less than half an ounce could be sent anywhere in the United Kingdom. The sender was responsible for payment. Previously, the recipient would be liable, making the system not only highly inefficient socially inequitable. To receive a letter would cost a labourer about a day’s wage.

Hill, who was born into a liberal-thinking, nonconformist family, was driven by a desire to improve society. He felt that his post office reforms, which would increase the circulation of letters, would would encourage industry, restore divided families and promote literacy. They may have done all those things and certainly his achievements earned him widespread praise, an honorary degree from Oxford and a knighthood, as well as a lasting legacy: his system was replicated across the world.

But there are other less well-known aspects of this talented man, and in one particular project, in which he documented the movements of a young woman and her alleged murderer on the night of 26 May 1817, he combined several of them, notably his skills as a land-surveyor, cartographer and educator.

Rowland Hill’s father, Thomas Wright Hill, was a former brassfounder who set up Hill Top School in Birmingham. It was later renamed Hazelwood School. His sons Rowland and Matthew took over the running of the school in 1819. The school later moved to Tottenham in north London.

Rowland Hill’s mother, Sarah Lea,was from St James’s, Birmingham. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, she was a woman of ‘strong character’ who made up for her husband’s deficiency in common sense. It was her suggestion to set up Hill Top school.

One of eight children, Rowland Hill was both sickly and prodigiously precocious. At five he constructed a watermill; at 12 he was working as an instructor at Hill Top, the school his father established at Lionel Street,1 Birmingham, primarily to educate his six sons. With other pupils at the school young Rowland set up a common-stock theatre company for which he wrote plays, painted scenery, built sets and put on hot-air balloon displays. In addition, tutored by Samuel Lines, the school’s drawing master, Rowland developed an interest in painting and sketching, and won a prize for one of his works.

There seemed to be nothing Rowland could not turn his hand to. He built a flat-bottomed boat, constructed a water clock and assisted at his father’s demonstrations of electricity at the Birmingham Philosophical Society. A project to draw up maps for a school atlas, started when he was 16, was one of the few that defeated him. Although he produced a map of Spain and Portugal he got no further. ‘It was, he wrote later, ‘a much greater undertaking than I at first imagined, owing to the great difference that exists in the works which it was necessary to consult.’ Despite failing to complete the project, the exercise must have been valuable experience for him and introduced him to some of the difficulties and questions involved in map-making.

No doubt, he would have preferred to have started from scratch and done the land-surveying, another of his hobbies, himself. In his journal, he recalled how he taught himself the principles: ‘I learned the art [of lands-surveying] as best I could; I might almost say I found it out, for I had then no book on the subject, and my father had no special knowledge of the matter.’

Once he had become sufficiently proficient, he sought to pass on his knowledge to his pupils. The ethos of Hill Top was to encourage practical knowledge, so together they mapped their playground and some of the local area.

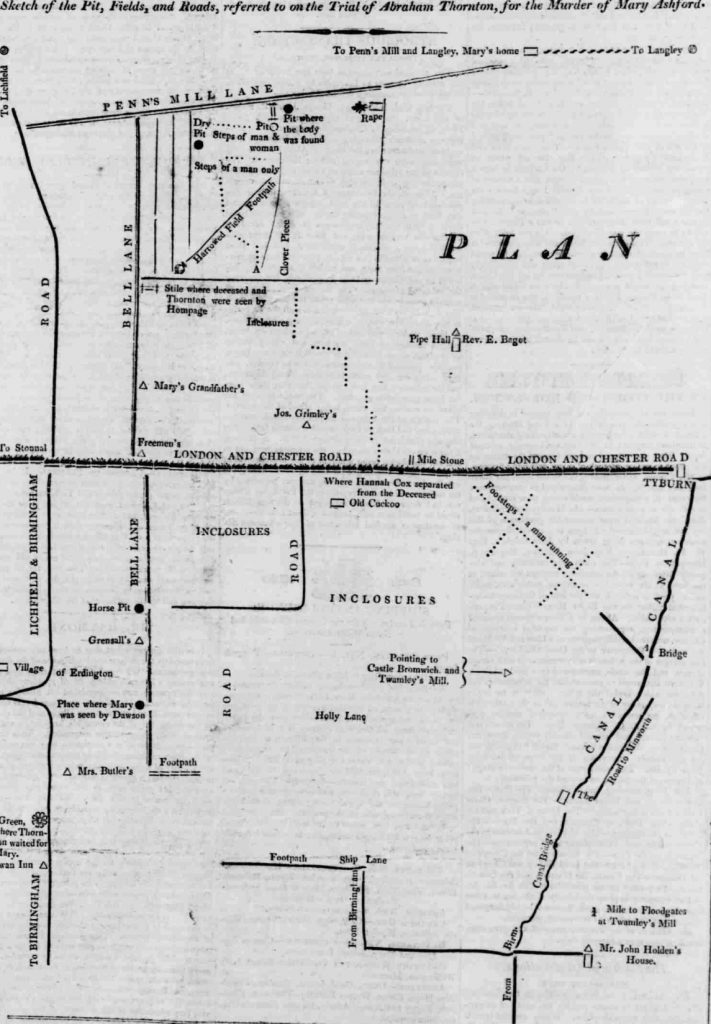

A crude map showing significant places in the murder of Mary Ashford, created using printers glyphs, printed in the Chester Chronicle on 17 November 1817 but probably copied from one published earlier in the Lichfield Gazette. © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD

On the morning of 27 May 1817 the body of 20-year-old farm servant Mary Ashford was found in a stagnant pool near the village of Erdington outside Birmingham. The crime shocked the neighbourhood. A prime suspect, Abraham Thornton, a local bricklayer, was quickly identified and charged, and soon afterwards a local paper published a crude map of the area where the murder took place. Hill wrote in his journal:

My drawing-master [Samuel Lines] published a portrait of the poor girl – taken, I suppose, after death – with a view of the pond in which the body was found; and one of the Birmingham newspapers (the Midland Chronicle 2) gave a rude plan of the ground on which the chief incidents occurred. This, however, being apparently done without measurements, and not engraved either on wood or copper, but made up as best could be done with ordinary types, was of course but a very imperfect representation.

As Thornton’s defence at his trial in August rested on alibi evidence, maps were a crucial part of his trial and both prosecution and defence commissioned their own versions. But, despite widespread feeling that Thornton was guilty, he was acquitted.

Mary Ashford, by Samuel Lines, a drawing master at Rowland Hill’s father’s school. Hill thought that Lines had viewed Mary’s body in order to produce a likeness, but no evidence of this exists. Published by Craddock & Joy in Birmingham. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

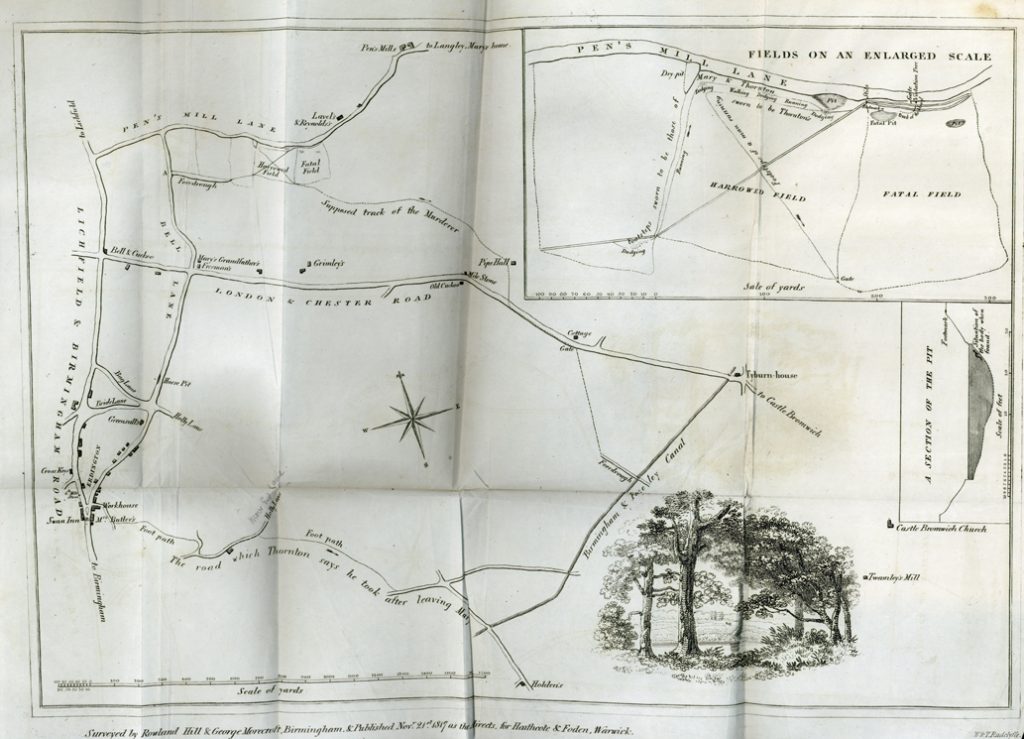

In November, interest in the case was reignited with the news that a civil suit (‘appeal of murder’) by Mary’s brother would give another chance of justice. Rowland Hill, aged 23 and still working at the school, wanted to contribute to a better understanding of the case. He was convinced that he could produce something better than the newspaper effort, and he was also sure that he could make money while doing so – the Hill family was not wealthy. He roped in his pupils and a man to whom he was teaching land-surveying to walk to Erdington to survey the area.

The copperplate scale map that resulted included detail of the area around the so-called ‘fatal field’ and a diagram of the position of Mary’s body in the pond, and was published in November 1817 in Birmingham and London (it was also printed in John Cooper’s report on the trial of Abraham Thornton and the subsequent court hearings in London).

Rowland Hill’s map sold for a penny a copy and was also printed in John Cooper’s account of the Warwick trial of Thornton and subsequent legal action in London (reproduced here). Soon after publication it was plagiarised. Hill’s brother Matthew suggested that he add a date at the foot of the map to establish copyright.

Hill made £15 from sales but unfortunately his work was so impressive it was soon plagiarised. He was incensed by this and wanted to sue but his brother Matthew thought this would be a waste of money and suggested instead that reprints include a date of publication.

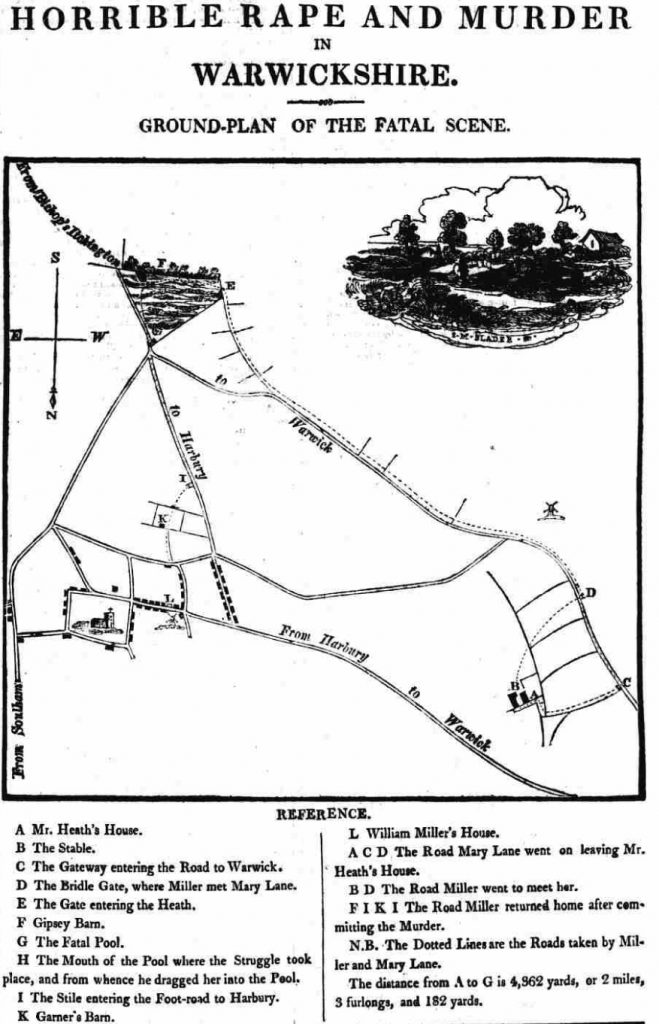

Ten years after Rowland and his team created their map, the body of Mary Ann Lane was found in a pit 30 miles from Erdington. The case had horrible similarities to Mary Ashford’s. Perhaps it was those similarities that prompted newspapers to publish a map for the greater edification of their readers. The influence of Rowland Hill’s style is obvious.

After the murder of Mary Ann Lane, Bell’s London Life published a copperplate map of the Harbury area. 26 August 1827. © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD

My book The Murder of Mary Ashford is available from Pen and Sword and all online outlets.

Sources

Hill, Sir Rowland and Hill, George Birkbeck (1880). The Life of Sir Rowland Hill and the History of Penny Postage. London: Thomas de la Rue & Co.

Bartrip, P. W. J., ‘A Thoroughly Good School’: An Examination of the Hazelwood Experiment in Progressive Education. British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Feb., 1980), pp.46-59.

Golden, Catherine J., ‘Rowland Hill (1795–1879). Victorian Review, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Spring 2011), pp. 9-13.

Smyth, Eleanor C. (1907). Sir Rowland Hill: The Story of a Great Reform. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

Stephen, Sir Leslie, ed. (1921-2). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol 9, pp. 876-7. London: Oxford University Press.