On 26 May 1817, Mary Ashford, a 20-year-old native of Erdington, walked in to Birmingham from her uncle’s farm at Langley Heath, stopping off at her best friend Hannah Cox’s house to leave clothes she would later change into to go to a Whitsuntide party at Tyburn House. She made this journey to the market in High Street, Birmingham twice a week and habitually stood near the Castle Inn to sell her eggs and butter.

Mary was considerably older than the young girl shown in Henry Walton’s The Market Girl (first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1777), who looks to be only about ten or eleven. She was probably posed by Walton’s niece and that may account for a certain lack of authenticity about her. The scene is very peaceful and the town in the distance rather sleepy, quite unlike the bustling metropolis of Birmingham. Still, it emphasises that people often walked long distances in order to sell their produce at market.

In contrast, Mary Ashford’s journey of six or seven miles was along a busy route towards a rapidly industrialising city, and she would have seen and greeted many working people along the way. After crossing Salford bridge over the Birmingham canal, passing a water mill on her right, and skirting the grounds of Aston Hall with its adjacent church, where she and her siblings were christened, she entered the city through Aston Street. 1

She would also have had to carry, very carefully, the eggs and butter the whole way, probably in a basket. She was a strong but slightly-built girl and it probably did not make it easier that she had a ‘natural condition upon her’ (this was a crucial issue in the terrible events that were to follow and how they were interpreted – but you will have to read the book to find out more about this).

What greeted her at Birmingham? Markets were known as rough, busy places, not for the faint-hearted. Mary Ashford, quite as much as her female customers, would have been well able to cope both with the press of crowds and over-familiar banter from her fellow hawkers, and at times she probably would have had to fend off outright sexual assault.

In 1820 the Birmingham Journal carried this description of the market in Birmingham:

The most unpeopled streets of a former period were now busy with life and bustling activity. From morning to night continually swept along them a busy tide, and trains of heavy carts extending for more than a mile, loaded with coal and lime, and bars of iron from the district around, stretched from one street to another and far beyond them.

On market days there was great business and bustle. Crowds of country people gazing in at windows blocked up the narrow footway at the risk of being overturned or of danger to their limbs from handcarts and wheelbarrows rolling inside the kerbstone. Ballad singers and blind beggars swarmed at every corner. Here a brawl, the sequence of the sloppings from a trundled mop in the face of a passer-by. There a crowd round some baker’s horse with bread panniers occupying the breadth of the pathway and those within playing at pitch-loaf, to the danger of some unwary inhabitant. Heaps of coals lying upon the pavement from morning to night and mud heaps all around.

Not much of the noise and bustle of Birmingham market is conveyed in this 1827 engraving based on a watercolour by David Cox (1783–1859), but it does show the position of Nelson’s statue, which was unveiled on George III’s golden jubilee in 1809, in front of St Martin’s church (the statue has since been moved a couple of times, but is now sited close to its original position). Mary used to sell her butter and eggs by the Castle Inn (or Hotel) which was between the statue and the corner of Castle Street (the exact spot is marked as a green “10” on the map at Eighteenth Century Birmingham).

In 1801, the Birmingham authorities started to clear the higgledy piggledy shops and dwellings in the area beyond St James’s Church known as the Bull Ring 2 and moved the main market there. The High Street market remained, perhaps smaller than it once was, but still busy thriving by the time Mary sold her goods there.

Mary was a well-known and well-liked in her home village of Erdington and also in Birmingham. After her death, numerous broadsides and songsheets about her murder were published and sold throughout Warwickshire and a three-act play by George Ludlam, titled The Mysterious Murder: Or, What’s the Clock?, was performed to appreciative crowds at markets and fairs even before the legal process involving her alleged rapist and murderer was exhausted. The audiences would have been made up of people of the same rank and class as Mary – farm labourers, domestic servants, carters, small businesspeople. These people were the frequenters of the markets and were her natural supporters, whether they knew her personally or not. Naturally, they were outraged and dismayed at the subsequent failure to punish her killer and the cynical tarnishing of her reputation that followed.

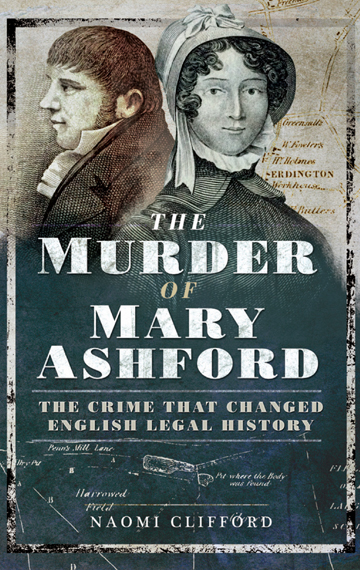

The Murder of Mary Ashford is available from Amazon UK, Pen & Sword and many other online outlets. You can also order via your bookshop.

- Pye, Charles, A Description of Modern Birmingham, Whereunto Are Annexed, Observations Made during an Excursion round the Town In the Summer of 1818, Including Warwick and Leamington (1819). Birmingham: J. Lowe.

- According to Eighteenth Century Birmingham the name is from the traditional spot where bulls were tethered before slaughter rather than because it was the site of bull-baiting.