For my book Unfortunate Wretches, about women hanged in the early 19th century, I have been looking at the relationship between servants and employers. Quite separately, for my next project, The Murder of Mary Ashford, I am also researching issues around rape. And, of course, because it was a theme in The Disappearance of Maria Glenn, I am interested in how teenagers, particularly female teenagers, are disparaged and disbelieved in the media and by their accusers.

For my book Unfortunate Wretches, about women hanged in the early 19th century, I have been looking at the relationship between servants and employers. Quite separately, for my next project, The Murder of Mary Ashford, I am also researching issues around rape. And, of course, because it was a theme in The Disappearance of Maria Glenn, I am interested in how teenagers, particularly female teenagers, are disparaged and disbelieved in the media and by their accusers.

As was so often the case, the voice of the victim in this story was almost completely unheard. Her allegations were reported second-hand, and events were related, in court and in print, entirely through the words of men, most of whom were both unsympathetic and biased against her. Nevertheless, the story gives some comfort. One man at least appeared to understand the situation Hannah Whitehorn found herself in shortly after she entered the household of Captain Samuel Mills.

On Friday 13 August 1819, 15-year-old Hannah Whitehorn, a live-in servant for Captain Samuel Mills (or Milne or Milnes) in Smith Street, Chelsea, was dismissed by her master and sent home to her parents, who lived in Charing Cross. Later that evening, Mills left the house and spent the night and much of the following morning enjoying himself at Vauxhall Gardens on the south side of the Thames.

Smith Street, London

Hannah, who had only the day before written to her mother in distress, had an appalling tale to tell about her experiences at the hands of Captain Mills. At midnight on the day after she arrived at Mills’ house, the Captain had “pulled her into the parlour and gave her some noyeau [nut liqueur], which made her sick and obliged her to go into the garden. After she came in, he again called her into the parlour, gave her the candle, and pushed her up stairs, notwithstanding all the resistance, she could make. He prevented her from going into her own room, and pulled her into his.” Then he raped her.

Diligence and Dissipation: The Modest Girl rejects the Illicit Addresses of her Master (1797). After James Northcote. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund.

Mr. Whitehorn, who was later described as “almost deranged” with grief at the treatment of his daughter, and Mrs. Whitehorn, who was “lame and helpless”, went straight to Mr. Price, who had found Hannah the job with Mills. Price immediately dispatched a letter to the Captain informing him of Hannah’s allegations. Mills, a 48-year-old former Army captain who described himself as a “magistrate and housekeeper [householder]”, found it waiting for him when he returned from Vauxhall. Incensed, he wrote to Price to deny Hannah’s story and on the Monday presented himself at Mr. Price’s abode to discuss the matter. There Price told him that Hannah was now also claiming that he had given her “a certain complaint” (sexually transmitted disease). At this he went to see the famous surgeon and anatomist Mr Astley Cooper, who gave him a clean bill of health.

At Price’s house, Mills demanded a meeting with Hannah’s mother, who arrived with a police constable. Mills was arrested and taken before a magistrate; Hannah related her story and the Captain was committed to prison. Hannah was then examined by medical men, the well known George Fincham of Spring Gardens, and Hugh Campbell, who described himself as a former lieutenant (whether in the army or navy is not clear), and a non-practising medic. Campbell found the girl in “a wretched condition”, was instantly struck by her plight and decided to do all he could to support her.

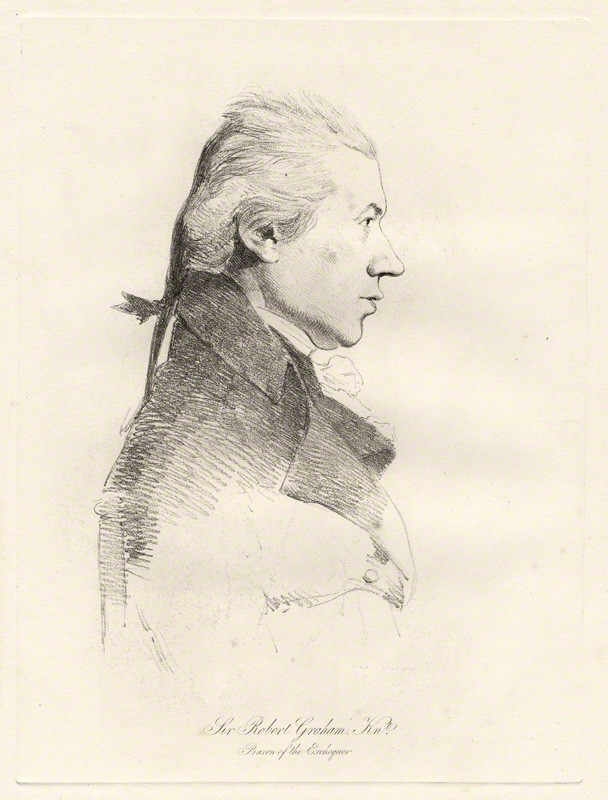

On 15 September Mills’s case came up at the Old Bailey, where he was defended by top barristers John Adolphus and John Barry. Saunders’s News-letter1 described Mills in court as “a middle-aged man [who] was fashionably dressed in black.” Under an arduous cross-examination Hannah gave evidence concerning her life in the Mills household. She admitted that she had sat talking with her master in the parlour each night, sometimes to 12midnight or later, but she faltered so much in her replies (“glaringly inconsistent”) that the judge, Robert Graham, asked her counsel whether the case should be pursued. It transpired that she may have had a disease, but perhaps not a sexually transmitted one as the diagnosis was not certain. Unsurprisingly, the jury conferred briefly and acquitted Mills.2

At this point, the court became chaotic. As the verdict was being recorded, Hugh Campbell, the medic who had examined Hannah, furious that Mills was getting away with his crime, leapt up and from the witness box declared that he had come to do justice to Hannah’s cause. Hannah had a good character, he said, and had arrived at Mills’s house as a virgin but emerged “polluted.” Hannah had been treated shamefully and cruelly.

“Who are you, or what are you? Are you a professional man?,” asked the judge.

“I have been in the service of my country: I have studied and I understand surgery and medicine, though I don’t practise as a professional man,” replied Campbell and continued his declamations, despite the objections of Adolphus and Barry. He was dragged from the witness box and only reluctantly left the court itself, still expounding on the injustice of the verdict.

His campaign did not stop there. First he wrote to the judge. Their correspondence was published in the newspapers.3 Next he published the correspondence in a pamphlet 4 which he had prefaced with the following motto:

“——multi

Committunt eadem diverso crimina fato;

Ille crucem pretium sceleris tulit hic diadema” —Juvenal

“Ev’ry age relates that equal crimes unequal fate have found;

While one villain swings, another villain’s crown’d.”

Captain Mills, perhaps encouraged by his legal advisors, now planned to rehabilitate his damaged reputation by pursuing his enemies. He launched a prosecution of Hannah for perjury in her account5 and sued Campbell for libelling him in the pamphlet.

Sir Robert Graham (1744-1836) by William Daniell, after George Dance, soft-ground etching, published 1854?

Hannah’s case came up in the Court of King’s Bench at Westminster Hall in May 1820. This time, Mills employed James Scarlett, one of the most successful and expensive lawyers around, to prosecute. It did not go well – for Mills. In the witness box he claimed that he had dismissed Hannah because he was disgusted by her personal offensiveness (“extreme dirtiness”)6 and said that he dined out constantly, during which time she was free to leave the house herself, the imputation being that she must have picked up a disease on those occasions.

However, under cross-examination he could not adequately explain why so many domestic servants had left his employ (eight women in five months, one of them very suddenly) nor why two of them had lodged complaints against him at the police office in Queens Square (although none of them alleged rape). While it became clear that Hannah had told no one of the attacks on her for the 16 days she lived in the household, an 11-year-old fellow servant remembered that she had been ill the day before she was sacked and had written to her mother. Hannah’s friends stood up for her, including two respectable gentlemen and the Rev. John Day, whose day-school in Orange Court, Leicester Square, Hannah had attended. Despite the direction of the Lord Chief Justice, the jury declined to find Hannah guilty and the case was dismissed.

The following month Hugh Campbell appeared in the same court to answer charges of libel brought by Mills, who once more employed the services of James Scarlett. Campbell, defending himself, presented an eccentric argument. His motivation was to encourage “purity and virtuous feeling among women in the inferior walks of society” he declared, and invoked “a Royal proclamation for the encouragement of religion and morality: in the spirit of which proclamation he contended he had acted, and upon the letter of which he was entitled to reward rather than to punishment.” He declared himself confident that the jury would acquit him – which they did.

The Gourmand, by Thomas Rowlandson. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

At this point, our protagonists – Hannah, a girl from a humble family who had courageously alleged that her employer had attacked her and endured scepticism, denigration and insult, and Campbell, her condescending but valiant defender – fade into history7. Not so Captain Mills. He pops up again ten years later, in circumstances that leave many questions, while also indicating that his behaviour towards Hannah was part of a pattern.

In 1830, Captain Mills described to a magistrate at Marlborough Street how he had noticed people lurking outside his home in Down Street, Piccadilly. “From circumstances which had already occurred,” he knew they were there for him. He had managed to avoid these people until one morning, while out in his tilbury,8 he was soundly horsewhipped by Lieutenant William Burt, who only stopped when a passing police officer intervened and arrested him.

In the magistrates court, Burt did not bother to deny the charge, and his manner was triumphant rather than repentant. When Mills claimed that the only reason he did not challenge him to a duel was that Burt was not a true gentleman, having been excluded from the United Service Club, he announced that he “considered himself fully respectable, at least in every sense of the term, as Captain Mills, although he could not boast of having so much notoriety in Bow-street police-reports as the Captain had.”

- 22 September 1819.

- OBPO t18190915-70. As Mills was acquitted, details of the case were not given.

- Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 25 September 1819.

- “A Letter to Mr. Justice Graham” cited in Evening Mail, 26 June 1820.

- There are parallels here with the case of Maria Glenn, whose rollercoaster ride through the courts of England landed her in a similar situation.

- Evening Mail, 31 May 1820.

- If you can help me with identifying what happened to them please leave a comment.

- An open, two-wheeled carriage.

Poor girl. And how sad it is that upright ‘sportsmen’ can still get away with it, and their victims slandered.

Yes, too true – nothing changes, it seems.