James Scarlett was the foremost barrister of his age. He earned more and won more cases than any other lawyer, so it is perhaps a surprise to learn that he was not a good orator or even a particularly good lawyer.

Scarlett was born in 1769 in Jamaica, where his family owned many slave plantations. They traced their descent from Thomas Scarlett who distinguished himself at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.

Aged 15 he was sent to England, where he was admitted as a member of the Inner Temple. Like his older brother, Philip Anglin Scarlett, he was predestined for the law, although his family had few professional legal connections. He studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he worked hard and graduated in 1789. Afterwards, on the advice of his friend Samuel Romilly, he took up quarters in the Temple, devoted himself to studying law and completed his pupillage.1

He was called to the bar in 1791, aged only 21, graduating M.A. three years later and joining the northern circuit and Lancashire sessions.

In 1792 he married Louise Henrietta Campbell.

At first, he did not shine particularly but by steady application he managed to rise, and it was this determination that characterised his career.

What gave James Scarlett an advantage over all others? An appealing persona, an attractive bearing and a well-modulated voice certainly helped. Many lawyers have those attributes, of course. What made the difference was his thorough understanding of human nature.

His strategy was to focus on the jury. His opening speeches were legendary as they laid out the facts of the case clearly and efficiently. He did not try to bamboozle the jury with eloquence and never pre-prepared speeches. He spoke off the cuff at all times and never took notes. He hardly ever cross-examined.

According to his son, Peter Campbell Scarlett, he rarely read briefs before a case, preferring to interrogate attorneys instead.2 Perhaps this gave him more insight into the salient facts of the case. It certainly would have saved him time and allowed him to become involved in more cases, and therefore earn more money.

Scarlett was quick-witted and could turn an exchange on its head. In a breach of promise case in which he appeared for the defendant, he was having difficulty cross-examining the mother of the plaintiff, a titled lady, who was supposed to have cajoled the defendant into the engagement. “You saw, gentlemen of the jury, that I was but a child in her hands. What must my client have been?“

Sometimes he could be bested.

Sir James was a noted cross-examiner and verdict-getter, but on one occasion he was beaten. Tom Cooke, a well-known actor and musician in his day, was a witness in a case in which Sir James had him under cross-examination.

Scarlett: “Sir, you say that the two melodies are the same, but different; now what do you mean by that, sir?”

Cooke: “I said that the notes in the two copies are alike, but with a different accent.”

Scarlett: “What is a musical accent?”

Cooke: “My terms are nine guineas a quarter, sir.”

Scarlett (ruffled): “Never mind your terms here. I ask you what is a musical accent? Can you see it?”

Cooke: “No.”

Scarlett: “Can you feel it?”

Cooke: ” A musician can.”

Scarlett (angrily): “Now, sir, don’t beat about the bush, but explain to his lordship and the jury, who are expected to know nothing about music, the meaning of what you call accent.”

Cooke: “Accent in music is a certain stress laid upon a particular note, in the same manner as you would lay stress upon a given word, for the purpose of being better understood. For instance, if I were to say, ‘You are an ass,’ it rests on ass, but if I were to say, ‘You are an ass,’ it rests on you, Sir James.”

The judge, with as much gravity as he could assume, then asked the crestfallen counsel, “Are you satisfied, Sir James.”

“The witness may go down,” was the counsel’s reply.

In court Scarlett’s manner was nonchalant but he could also be a bully. This was especially apparent in his exchanges with Charles Abbott (later Lord Tenderden), the Lord Chief Justice. Abbott had at one time been Scarlett’s junior. When they worked together Scarlett had often belittled Abbott, preventing him from examining witnesses or from making points of law. It was a dynamic that continued to operate despite Abbott’s elevated position.

The timid junior, become Chief Justice, still looked up to his old leader with dread, was afraid of offending him, and was always delighted when he could decide in his favour.3

Abbott was especially vulnerable when Scarlett was conducting prosecutions for conspiracy. There was a long string of these where Abbott granted new trials on the grounds that the verdict was not supported by the evidence. Eventually his influence over Lord Tenterden was so marked as to become the subject of complaint at the bar.4

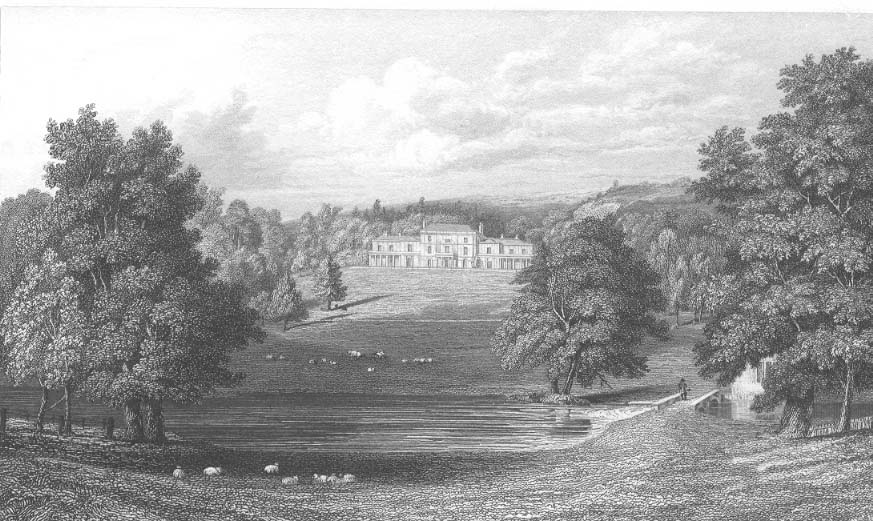

In 1807 Scarlett left the Lancashire sessions and confined himself to the northern circuit and the Court of King’s Bench. He bought the seat and estate at Abinger in Surrey in 1813, and was called to the bench of the Inner Temple three years later. From then until the close of 1834, when he was appointed Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer, Scarlett “had a longer series of success than has ever fallen to the lot of any other man in the law”. The most he made in one year at the bar was £18,500, a huge sum at the time. His success was the subject of much gossip. Lawyers joked that Scarlett had invented a machine that made judges nod their heads at his arguments.5

Like many lawyers, Scarlett combined a career at the bar with one in the House. He entered Parliament in 1819 as a Whig member for Peterborough and later represented Malton. He was appointed Attorney General and knighted by Canning in 1827, resigning in 1828 when Wellington came in. He returned to government in 1829 and left again in 1830. At this point, deeply opposed to the Reform Bill, he turncoated and joined the Tories. He was elected for Cockermouth in 1831 and Norwich in 1832 (until 1835, when he was raised to the peerage as 1st Lord Abinger.

Despite a widely-praised maiden speech, Scarlett, who “reasoned too closely for a large assembly and came too late into Parliament to learn or practise the art of declamation”, did not shine at Westminster. His son attrributed this failure to “diffidence and want of moral courage”, remarking that “he was ever afraid of losing there the reputation he had acquired in Westminster Hall”.6

As Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer Scarlett had a reputation for unfairness and complaints were made about his domineering attitude towards juries. Ever the advocate, he had a habit of presenting only one side of the case to the jury, who often refused to submit to his direction for that reason.

In 1843 his conduct while presiding over the special commission issued for Lancashire and Cheshire was described in the House of Commons as “partial, unconstitutional, and oppressive.” The radical politician T. S. Duncombe’s motion for an inquiry into his behaviour was defeated by 228 votes to 73.

Louise Henrietta died in 1829. In September 1843, aged 73, he married 41-year-old Elizabeth Steere, the widow of the Reverend Henry John Ridley, the rector of Abinger. Barely six months later, on 2 April 1843, after doing his work in court at Bury St. Edmunds, Scarlett had a sudden stroke and died at his lodgings five days later. He was buried in the family vault in Abinger churchyard.

Addendum: 10 November 2015

Visit Mimi Matthews for an account of a scandalous crim con case defended by James Scarlett. As on many other occasions, including the case featured in The Disappearance of Maria Glenn, he used the tactic of wearing down the opposition by putting dozens of witnesses giving similar stories into the witness box.

- While a student, he became the guardian of a child whose family were friends of the Scarletts in Jamaica. Edward Moulton later changed his name to Barrett (it was his mother’s maiden name) and became the father of Elizabeth Barrett of Wimpole Street fame.

- Anglo-American Securities Regulation: Cultural and Political Roots, 1690-1860 by Stuart Banner. Law and History Review, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Summer, 2002), pp. 404-406. http://www.jstor.org/stable/744044.

- Lord John Campbell, The Lives of the Chief Justices of England, from the Norman Conquest Till the Death of Lord Tenderden, Volume 3, page 248. London, John Murray, 1849. Lord John Campbell was also James Scarlett’s son-in-law.

- Dictionary of National Biography, George Fisher Russell Barker, 1897. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Scarlett,James(1769-1849)_(DNB00)

- Landmark Cases in the Law of Restitution, Edited by Charles Mitchell, Paul Mitchell. Bloomsbury, 2006

- Brougham mss 23734, quoted in The History of Parliament.

Thanks for writing this. I’ve traced back my ancestry and I am a direct descent of this fellow’s aunt and he’s a distant cousin….an interesting read so thanks

Hi, out of curiosity, are you related to James Scarlett via Anglin or Tate. My maternal grandfather is a Tate. We are probably related.

My pleasure, Mary. I’m glad you found it useful. Scarlett was a colourful character and if he lived now, I feel he would be something of a TV celebrity.

/Users/wynyard/Desktop/Accidental discovery relating to spoons and forks.png

I am vexed trying to find a reference to your hero’s defence of the Silversmith Sandry accused of forging the Hallmarks on silver spoons and forks in 1833.

There must be a story there – but where to find it?