Never was a private individual’s decease more sincerely lamented than that of Sir Samuel Romilly.1

On Thursday 29 October 1818, on the Isle of Wight, where she had been taken in an effort to find a cure for her long-standing and painful illness, 45-year-old Anne Romilly died. Her children were bereft, but it was her husband, Sir Samuel Romilly, who felt her loss most acutely.

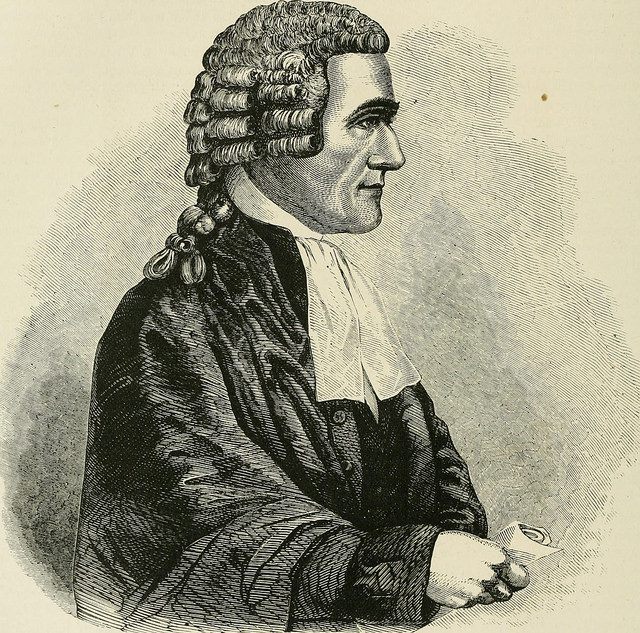

Samuel Romilly, from Old and new London : a narrative of its history, its people, and its places. London: Cassell, Petter, & Galpin, 1873

He and members of his family set out for his London home in Russell Square the next day, but during the journey his companions grew increasingly alarmed at his state of mind. Stephen Dumont, his best friend2, said later that during the journey to London Romilly was continually wringing his hands and complained of heat in his head. Dumont described him as a man “dying of an internal wound.”

By the time they reached Russell Square concern was so great that the family was reluctant to let him out of their sights. Romilly’s nephew Dr. Roget insisted on sleeping on a couch in his bedroom and called in Doctors Marcet and Babington, both of whom lived locally, to see him. He said his uncle was “uttering expressions in a strain of great perturbation.”

Plaque outside © sleepymyf on flickr

Early on Monday morning, Romilly’s 18-year-old daughter Sophia brought tea up to her father in his bedroom, while Dr. Roget went down to the drawing room. Romilly asked her to fetch the doctor up. In those few seconds, he slit his throat with a shaving razor. The footman Thomas Bowen, alerted by a commotion upstairs, saw him shooing Dr. Roget out of the bedroom. It was only as the door closed that he saw that his master was bleeding profusely. He and Roget forced the door and saw Romilly leaning over a basin, blood everywhere. He had severed his gullet. He could not speak – he could only make inarticulate signs and the pen and paper he was given were useless – so Dr. Roget laid him on the floor and sent for John Knox, a surgeon, who started to sew up the wound but he soon saw that it pointless and stopped.

Dumont, who had been to Holland House to see Romilly’s younger sons, who had been called back from school, arrived to find Thomas the footman in tears and Dr. Roget in despair.

I have an interest in Romilly because one of the main characters in my forthcoming non-fiction book, a barrister who believed that his niece had suffered a grave miscarriage of justice, admired him and quoted him in one of his campaigning pamphlets:

Truth has not always the semblance of truth; and that man can have had little acquaintance with proceedings of courts of justice, who has not sometimes observed, that facts, which at first appeared highly improbable, have nevertheless in the end been fully proved, and established.3

Romilly was a sophisticated thinker at a time when cases were too easily settled based on bare-faced prejudice and discrimination, a glib review of evidence and, often, easy acceptance of brutal and sadistic punishments. Unlike many of his generation, he aimed for purity of thought and soul, and that extended to his personal habits – He was known for rejecting comforts and affectations – perhaps the result of his austere and frugal beginnings in a household of pious French Protestants. He was down-to-earth and compassionate, committed to tolerance, liberty and fairness. Unfortunately, his achievements were modest, hampered by endemic corruption and by political reaction to the bloody excesses of the French Revolution. The times were not right for what he aspired to do, but he managed to lay a path for others to tread.

Romilly was born in 1757 in Soho, London in relatively humble circumstances. His grandfather, Etienne Romilly, had fled Montpellier after the revocation of Edict of Nantes in 1685, which removed all legal protection for French Protestants. In London Etienne married another Huguenot and his second son, Peter, worked as a watchmaker and jeweller to the King based in Broad Street. Samuel was from an early age noted for his intelligence and application (he has been described as “almost self-educated”) but he also had a gloomy disposition and a morbid imagination.

Romilly was no stranger to depression. As a child he had been subject to dark and morbid thoughts. As an adult, he worked exceptionally hard and, unlike many lawyer-politicians of the age, had few “pursuits” outside his family, to whom he was devoted. He was well aware of his melancholy nature. A few days before Anne died, fearing that he would buckle under the strain of the inevitable, he put his affairs in order and made arrangements for his children, the youngest of whom was only eight.

As a young man he had the foresight to use a legacy of £2,000 to train as a solicitor but he soon changed direction and, aged 21, headed for Gray’s Inn and a career as a barrister.

Anne, Lady Romilly

On a tour of Europe in 1781 he cultivated friendships with Etienne Dumont and Honore Mirabeau. He was also close to Jeremy Bentham and the Earl of Shelburne (Marquess of Lansdowne)4, whose attention was caught by Romilly’s 1784 paper on the rights of juries in libel cases. It was through Shelburne that Romilly met his wife Anne Garbett, whose father was Shelburne’s secretary. They announced their engagement after a courtship of only 10 days. The Observer recounted that he told Anne he had to make two fortunes before they could marry: one for the support of his parents and another for her. They were married in in 1798 at the parish church of Knill in Herefordshire.

He had two main areas of interest at this time: the French Revolution (some of which he had witnessed) and the reform of criminal law. He wrote anonymous pamphlets on both. Like many lawyers, he went into politics. In 1792 Lansdowne offered him a seat in Parliament (Calne), which he turned down on the grounds that their relationship would suffer if his political opinions differed from his patron’s. He was determined to be independent.

When Addington came to power he promoted Romilly, who saw his opportunity to bring in reform of statutory punishments for relatively minor offences. He also revisited France in 1802 but by now he, as were many others, thoroughly disillusioned with its repressive nature.

In 1805 he again turned down a seat in the Commons, this time offered by the Prince Regent, pleading a desire for independence but also privately appalled at the thought of being in the pay of such a person: “I was averse to being brought into Parliament by any man, but by the Prince almost above all others.”

In 1806, after Pitt died, Romilly was invited by Fox to be Solicitor General. He was almost universally admired in this role:

Of all the appointments, the legal ones were then considered most satisfactory; that of Sir Samuel Romilly could not have been improved upon. Lord Buckingham

[Romilly] stands at the head of the profession (as I am informed by everyone), both in point of legal accomplishment, general information, and respectability. Francis Horner

Romilly spoke against the slave trade, calling it “robbery, rapine, and murder” and in 1807 introduced a bill to change the Bankruptcy Laws. He succeeded in carrying through some minor legal reforms. Capital punishment was to be no longer exacted for theft from the person5, for stealing from bleaching grounds6, for soldiers and sailors caught begging without a permit. There was mitigation in the law of treason and attainder.7 But sheep stealing remained on the statute book as did the punishments of hanging in chains, the pillory, stocks and ducking-stool.

The Observer devoted almost two pages to the death of Samuel Romilly, an account of the inquest held the day after he died at the Friend in Hand public house in the Colonnade, Bernard Street off Russell Square, before Thomas Stirling, a long summary of his career, details of his funeral arrangements and a poem. The inquest found that Romilly had cut his throat in a state of temporary mental derangement. Dr. Roget was too distressed to attend.

Sir Samuel and Lady Anne Romilly were buried together at Knill, where they had married.

Romilly’s children lost both their parents in the space of four days, and the nation lost a gifted and compassionate law reformer. We can perhaps speculate that the emotional frailty of this upstanding, loyal and principled man gave him insight into the lives and motivations of those who transgressed.

Further reading

Patrick Medd, Romilly: The Life of Samuel Romilly, Lawyer and Reformer. London: Collins, 1968.

- The Observer, 8 November 1818

- Swiss preacher and publicist

- The Speeches of Sir Samuel Romilly in the House of Commons, Vol II. London: John Ridgway and Sons, 1820, page 436 gives a slightly different version: “Truth has not always the semblance of truth; and no man can have had much experience of judicial proceedings without having sometimes seen that facts, which at the first statement of them appeared in the highest degree improbable, have nevertheless in the end been fully and satisfactorily established.”

- William Petty, Whig statesman and Prime Minister 1782-1783, during the last months of the American War of Independence

- From 1808 the definition of “theft from the person” was widened to include any theft from the person, rather than merely theft where the victim was unaware of the crime

- Places where long lengths of fabric were spread on the ground for bleaching and drying

- Attainder or ”corruption of blood” arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (a felony or treason) and entailed losing not only one’s property and hereditary titles, but typically also the right to pass them on to one’s heirs.

[…] Cambridge, where he worked hard and graduated in 1789. Afterwards, on the advice of his friend Samuel Romilly, he took up quarters in the Temple, devoted himself to studying law and completed his […]