Typing was not offered at my secondary school so twice a week, in the dark and rain, I caught a bus to North Kensington to bash out pretend invoices on a huge manual machine. Typing turned out to be my most directly useful qualification and meant I could always earn a living. For girls in the Long 18th Century sewing had the same function. It was a transportable skill that would always guarantee you work of some kind. Like many working-class girls, female orphans and children abandoned to the Foundling Hospital were taught plain sewing, spinning and knitting, in order to ensure they had an income.

In the first post of this series, I looked at genteel and aristocratic women who sewed. Here I cover needlework for payment. Women earning their living from sewing were mostly, but not exclusively, working-class.

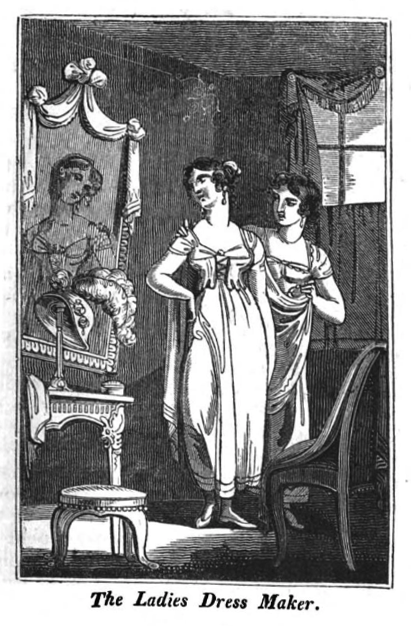

But how did most women experience life as a needleworker? Women sewed both within and without the home, of course. Sometimes they were independent providers – dressmakers, mantua makers and milliners benefitting from the intense interest in fashion amongst the rich by helping women achieve the fashion looks they aspired to. They had to be good designers and to be competent with the needle, but they also needed diplomacy skills. As the author of The English Book of Trades put it, “the Ladies’ Dress-maker’s customers are not always easily pleased; they frequently expect more from their dress than it is capable of giving.”

And, behind the scenes, the work was arduous:

The business of a Ladies Dress-Maker and Milliner, when conducted upon a large scale and in a fashionable situation, is very profitable; but the mere work-women do not get any thing at all adequate to their labour. They are frequently obliged to sit up very late, and the recompense for extra work is, in general, a poor remuneration for the time spent. From The Book of English Trades (1818).

The Ladies Dress Maker, from The Book of English Trades and Library of the Useful Arts (1818).

James Gillray’s satirical cartoon from 1800 shows a cramped milliner’s/dressmaker’s workshop which was probably more typical than the elegant salon in The Book of English Trades. Gillray depicts the exiled stadtholder William V, Prince of Orange, who is trying to recover his ‘indispensibles’ by thrusting his hand up the flimsy skirts of two seamstresses. It’s a reference to the Dutch colonies he gave away to the British but it also makes the point that such women are seen as sexually available. Notice that they look surprised but don’t resist.

James Gillray, The man of feeling, in search of indispensibles; a scene at the Little French Milleners A number of disputes having arisen in the Beau Monde, respecting the exact situation of the ladies’ indispensibles (or new invented pockets) whether they were placed at the ancle [i.e. ankle], or in a more eligible situation, the above search took place, in order to determine precisely the longitude of these inestimable conveniences (1800), published by Hannah Humphrey, During his exile in Britain after the Batavian Revolution, William V, Prince of Orange instructed the governors of the Dutch colonies to hand them over to the British for ‘safe-keeping’ and in 1799 he ‘sold’ a fleet of captured ships to the Royal Navy. Library of Congress LC-DIG-ds-07296.

William Holl Jr, after William Powell Frith, Kate Nickleby (1848). Although set after the Georgian period, the situation of dressmakers and milliners in Dickens’ novel Nicholas Nickleby had not substantially changed. They were subject to sexual predation and economic exploitation. NPG D38965 © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Heilmann’s idealised portrait, a well-dressed seamstress in a domestic setting and wearing a mob cap casts her eyes down demurely, seemingly intent on her work, but she is showing s just enough bosom to be interesting and the cloth she is working on falls between her parted knees. Subservient, poorly paid, sedentary, passive, the seamstress offers the perfect male fantasy.

Print after Johann Kaspar Heilmann, Domestic Amusement: The fair seamstress (1764) Lewis Walpole Library .

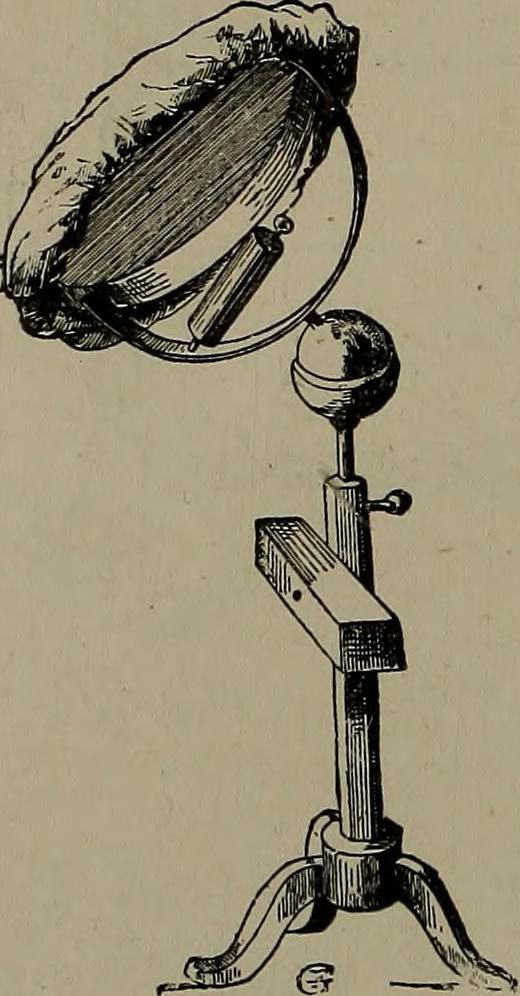

Possibly the most exploited group of needleworkers was the parish apprentices, in many cases indentured into virtual slavery for unscrupulous employers. In my book Women and the Gallows 1797-1837 I tell the story of 61-year-old Esther Hibner, who was hanged in 1829 for murdering 10-year-old tambour-maker Frances Colpitts. Frances was forced to stand for hours in Hibner’s King’s Cross workshop embellishing and embroidering Brussels or Nottingham net. The notorious case exposed the dreadful conditions young tambour-makers suffered in order to supply highly fashionable fabrics to a competitive market, but did not lead directly to improvements in their treatment.

Tambour embroidery frame, from Embroidery and Lace by Ernest Lefébure and Alan S. Cole. London: H. Grevel (1888).

Needlework as a money-making occupation was not confined to the working-class. Mary Wollstonecraft thought the repetitive and pointless nature of domestic needlework performed by middle-class women affected their thinking power, turning them into frivolous drones. Mary Lamb, writing in 1815,1 agreed, asserting that “Needlework and intellectual improvement are naturally in a state of warfare,” and proposing that needlework is never done except in return for money.

Mary, who was mentally unstable throughout her life, had a particular reason to be suspicious of needlework, even when it was done for profit. In 1796, aged 31, she was working at home as a seamstress making ladies riding coats when she killed her mother with a carving knife after an altercation with their apprentice. Although the family was middle-class, they were relatively poor and Mary worked to supplement their income. In the reported opinion of the Magistrate who sent her to an private asylum rather than charge her with murder:

It seems the young Lady had been once before, in her earlier years, deranged, from the harassing fatigues of too much business. —As her carriage towards her mother was ever affectionate in the extreme, it is believed that in the increased attentiveness, which her parents’ infirmities called for by day and night, is to be attributed the present insanity of this ill-fated young woman. Morning Chronicle, 26 September 1796

“Too much business” implies that the pressure of work in circumstances tipped Mary, who was held in high affection by her family, even after the killing of her mother, over the edge. When Mary recovered she was released and was free to pursue, with her brother Charles, her literary interests. When her mental condition deteriorated she was returned to the asylum.

Mary Lamb (1764-1847)

As we think of those women toiling in poor light to meet gruelling deadlines, for poor pay and little appreciation, perhaps we should also consider the people who make our clothes now, wherever in the world they are, and try to ensure that we are not replicating the terrible lives of Georgian needlewomen.

The needle was an archetypally female instrument; so forged in femininity that, like the distaff and the spinning wheel, it could stand as an emblem for woman herself. Tailoring was a masculine trade, but no male householder expected to do his own plain sewing. Only sailors and soldiers sewed for themselves. Amanda Vickery, The Guardian, 17 October 2009

In the final part of this series I look at the work of women who used needlework to produce art.

- In an essay, On Needlework, in the British Lady’s Magazine and Monthly Miscellany.