As we all know, there’s work and then there’s ‘work’. Working-class women in the Long 18th Century worked, that is they laboured, to earn money, and sometimes that included needlework – sewing clothes, household items and industrial items, or making lace and embroidery, such as tambour. ‘Work’ was the occupation of many genteel women and girls. This could be mending or it could be fancy decorative work: embroidering a tablecloth or a screen, for instance. There was also something else: sewing as art. Women, largely excluded from the male-dominated art world, found many ways to create and to earn their keep doing so, but often they had to use their ingenuity to do so. Wax, shells, needlework, often derided as mere craft, are part of that tradition.

The type of needlework women did was determined by her social rank and her circumstances. Here I look at sewing for pleasure by aristocrats and genteel women. Part 2 looks at sewing as a job and Part 3 covers how women used needlework to create art.

Unknown artist, Lady Jane Mathew and Her Daughters, c. 1790. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Lady Jane Mathew (née Bertie) – shown on the left in the painting – was the wife of General Edward Mathew, Governor of Grenada. The sewing shown is a pastime rather than a duty, and the portrait is an advertisement for the qualities of these unmarried women, as they display gentility of nature, competence in domestic matters and patient application. Note the serious environment (no smiling is going on) and the classical relief on the wall. One of the women shown in the portrait may be Anne Mathew, who married Jane Austen’s brother James in 1792, and who was described through Austen’s comment on Anne’s nieces: “Both prettyish; very like Anne; with brown skins, large dark eyes and a good deal of nose.”1

Paul Sandby, Woman Seated by a Window (c. 1760-80). Royal Collection Trust.

Upper-class women tended to do crewel embroidery, using heavy wool threads on durable fabrics to create decorative floral designs to enhance clothing, bedding, draperies. There was also flat silk stichery, using silk threads on silk fabric, often made on a tambour (two hoops over which the fabric is stretched – more on tambour work done by parish apprentices in Part 2).

By the middle of the 18th century, upper-class women were using a variety of techniques to embellish clothes and household items. Knotting (or tatting), a way of creating a durable lace using knots and loops, on long strips of fabric, was a relatively easy technique. It did not need good light and could even be done on the move, in a carriage, for instance. In this portrait of Queen Charlotte and her daughter by Benjamin West, Charlotte the Princess Royal holds up some finished knotting sewn on to a coverlet. Again, the artist has been at pains to emphasise the serious, scholarly credentials of the subjects by showing books, classical busts, sheet music and papers.

Engraving after Benjamin West, Queen Charlotte with Charlotte, Princess Royal, 1778. Courtesy of The British Museum.

Middle-class women’s needlework tended to be a bit more practical than royalty and aristocracy. Although they would commission clothes from a seamstress and they might restyle old items themselves, using buttons, ribbons or braiding, or they might adjust a hem length for fashion or a different wearer. They also sewed uniforms for male family members serving with the Army.

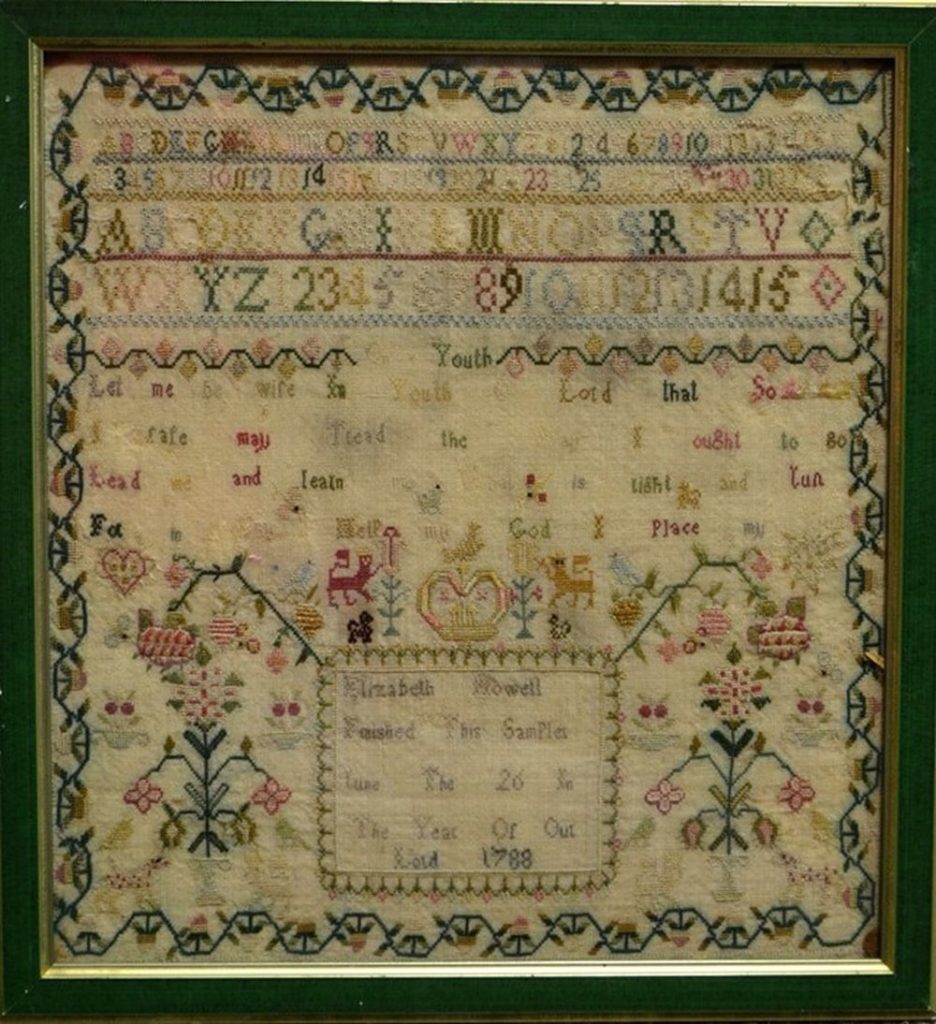

Women would teach their daughters literacy and maths using samplers, which could also be exercises in morals and piety, typically cross- or satin-stitching the Lord’s Prayer or the Ten Commandments for display.

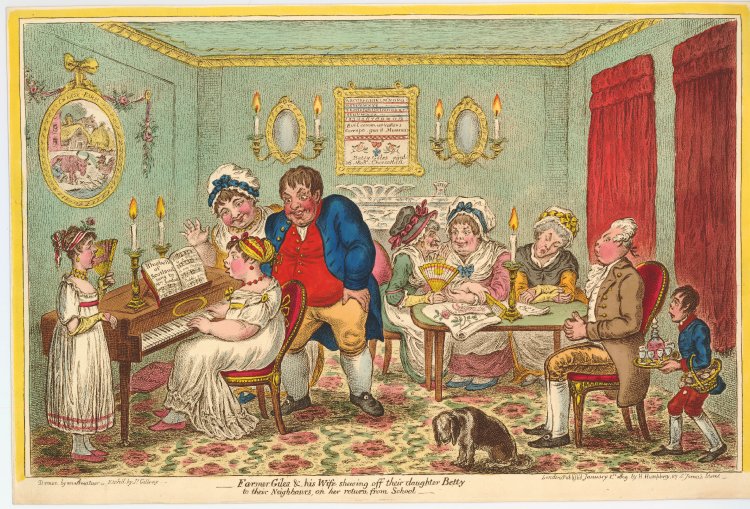

James Gillray, Farmer Giles & his wife shewing off their daughter Betty to their neighbours, on her return from school (1809). A sampler hangs over the fireplace and an embroidered cloth lies on the table, both no doubt completed by the accomplished Miss Giles. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Sampler by Elizabeth Howell (1788), auctioned by Kingham & Orme, March 2019.

Needlework, or “work” as it was called, would add to the mix of girls’ accomplishments, alongside drawing, dancing and music, to be used to promote them as matches for suitable men, but not everyone approved of teaching girls to sew.

… this employment [needlework] contracts their [girls’] faculties more than any other that could have been chosen for them, by confining their thoughts to their persons. Men order their clothes to be made, and have done with the subject; women make their own clothes, necessary or ornamental, and are continually talking about them; and their thoughts follow their hands. It is not indeed the making of necessaries that weakens the mind; but the frippery of dress. …Gardening, experimental philosophy, and literature, would afford them subjects to think of, and matter for conversation, that in some degree would exercise their understandings. Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

Wollstonecraft argued that teaching women needlecraft encouraged triviality and self-centredness. It was also unnecessary: ready-made clothing using cheaper fabrics (cotton from India for example) was increasingly available, and buying it would free up time for women to read. Further, to make your own clothes deprived working-class women of lifesaving work. Needlework was an indoor occupation. It kept women out of factories (where they were at risk from predatory men) and off the streets (ditto). Interestingly, antipathy to needlework was something Wollstonecraft shared with the conservative writer Hannah More, who also argued that it narrowed girls’ minds.

Did the repetitiveness of needlework hinder clear thinking? Could it lead to mental derangement? Part 2 includes the case of Mary Lamb, a seamstress making women’s riding coats, who wrote an essay titled On Needlework and killed her mother.

I wish to acknowledge the scholarship of Ellen Kennedy Johnson, in her dissertation Alterations: Gender and Needlwork in Late Georgian Art and Letters (PhD, University of Arizona, 2009).

- Jane Austen’s Family by Maggie Lane.)