The young woman whose abduction is the subject of my non-fiction book The Disappearance of Maria Glenn left St Vincent, and her beloved mother, as an eleven-year-old girl, just before the eruption of La Soufrière.

Eruption

At about noon on Monday 27 April 1812, the 28,000 inhabitants of St Vincent, both free and enslaved, witnessed the sudden and violent start of the eruption of La Soufrière, the huge volcano in the north of their tiny island. As great thunderous cracks split the air, the earth shook, a massive column of thick black smoke rose from the summit and volumes of red-hot sparks were spat into the atmosphere.

“In the afternoon the roaring of the mountain increased and at seven o’clock the flames burst forth, and the dreadful eruption began,” wrote barrister and plantation owner Hugh P. Keane. A hundred miles away on Barbados, Captain George Palmer Hawkins mistook the noise and smell for cannon fire and was convinced the French were attacking.

The volcano was not just a thing of terror — it was also sublimely beautiful, and three days after the volcano first stirred, Keane rose early to sketch the scene, with the volcano’s sulphurous vapours curling skyward and the air filled with layers of yellows, reds and rusts. His drawing, now lost, somehow made its way to an acquaintance, the artist J. M. W. Turner, who used it as inspiration for a work he showed at the Royal Academy in 1815. Turner’s painting is now in the collection of the University of Liverpool.

The anonymous writer of a letter to a merchant in Glasgow hired a sloop for a nighttime voyage of discovery along the coast.

“We arrived in sight of it [the mountain] and about six miles distant from the crater, just as the sun went down, when the mountain appeared on fire for several miles, and vomited out streams of lava, which carried everything before it.. before we were at anchor twenty minutes, a heavy fall of stones and sand obliged us to put to sea; luckily for us we received no injury.”

Another anonymous witness provided more detail:

“Although Kingston is at the distance of about twelve miles form the volcano, the inhabitants were so much alarmed, that many of them went on board of the vessels in the bay for protection, and it was not until past eight o’clock that one person could distinguish another, in consequence of the atmosphere being darkened by the quantity of ashes.”1

The next morning, the island was in darkness. A thick haze hung over the sea and the sky filled with yellowish black clouds. The island was covered with ash and fragments of lava—and the volcano was still rumbling. Gradually it settled back into silence.2 Two of the rivers had been completely dried up. The crops were ruined, and food had to be bought in from neighbouring islands. In all, about eighty people died, relatively few for an eruption of such force, although there were many injuries. Most of the dead and injured were enslaved people working in the sugar fields, killed in the rain of pumice.

Seismic instability

Unknown to the inhabitants of St Vincent, the eruption of La Soufrière was only one episode of a wave of huge seismic and tectonic disturbance stretching from one side of the world to the other. In December 1811 the Mississippi River valley had been convulsed by an earthquake so severe that it woke sleepers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Norfolk, Virginia. It was followed by intermittent strong shaking which lasted until March 1812 and the aftershocks continued for five years. 3 Only thirty-five days before La Soufrière erupted, the city of Caracas in Venezuela had been almost completely flattened by two huge seismic shocks. Ten, possibly twenty, thousand people died. And the instability was not over. There was worse to come. In Indonesia, Mount Tambora began to stir and rumble and a dark cloud appeared over its summit.

Reaction of the British press

The British press showed some interest in the eruption on St Vincent but the country was more preoccupied with the imminent naval war with the United States. In any case, the eruption could be dismissed as just another episode in the island’s turbulent history. The French had handed St Vincent over to the British in 1763 as a result of the Treaty of Paris but took it back in 1779. The British did not regain control until 1783. The Caribbean was the most important theatre of the Anglo-French War, which did not end until 1815, and the island of St Vincent was centre stage.

There was also internal strife on the island. French agents had fomented the rebellion of the so-called Black Caribs,4] the numerous racially mixed (and not enslaved) descendants of shipwrecked Africans and the indigenous islanders. The British crushed the uprising, known as the Brigands War, with force, killed the Black Carib leader and deported most of the black non-slave population to an island off Honduras. Only half of the five thousand making this involuntary exodus survived the voyage.5

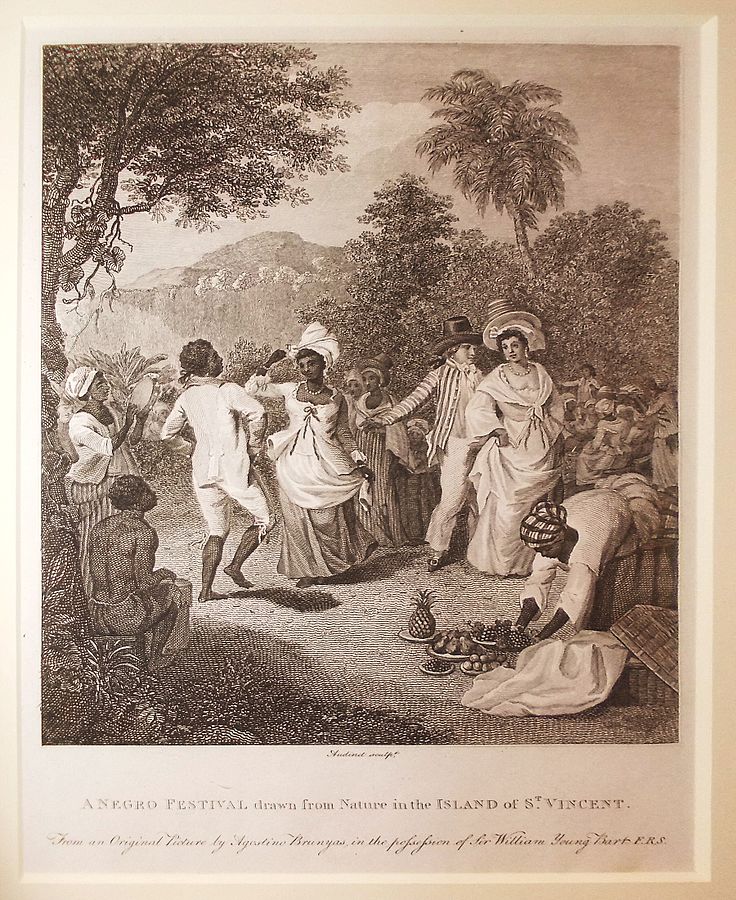

St Vincent itself was regarded as one of the jewels of the Empire. The volcano’s regular eruptions (there had been a major eruption in 1718) had rendered the earth richly fertile, ideal for growing the dominant crop—sugar. Between 1807 and 1834 the island was the leading producer of sugar in the Windward Islands, with the highest ratio of sugar to slave.6

Not only that, the island was exceptionally beautiful. On 10 September 1829 James Williamson, a ship’s surgeon, made a brief visit. He regretted not getting up early enough to catch the most spectacular view of the volcano, which was “still smoking”. All the same, he was entranced. “I have seldom seen so lovely a scene,” he wrote in his diary. “There were presented to you hills and slopes covered with the most beautiful clothing of nature you can conceive. Here were deep ravines—there gently declining plains—and the tout ensemble was such that I was perfectly enraptured. …St Vincent’s is of small extent, but is indeed a gem which tho’ insignificant in size shines with a brilliancy which raises its beauty and its value far beyond others of greater pretensions, in point of size.”7

Climate change

After 1812 a string of eruptions brought disruption to the global climate. In 1813 Mount Awu in the Dutch East Indies exploded, followed by Suwanosejima in Japan and by Mayon in the Philippines in 1814. The climax of this symphony of earthly disturbance was the world’s largest documented historic eruption. In April 1815, after rumbling and smoking for three years, Mount Tambora in the East Indies spewed thousands of tonnes of volcanic ash, gas and dust into the upper atmosphere.

The island of Tambora was nearly sheared in half. In the aftermath, a tsunami ripped the coastlines and for days the area was covered in darkness. The ash clouds and sulphur aerosols from the eruption, estimated as six times that of Mount Pinatubo in 1991—chilled the climate by blocking sunlight with gases and particles. The human cost was enormous. It is impossible to get accurate figures for the initial death toll but it has been estimated that ten thousand people were killed during the eruption, probably by pyroclastic flows, and a further thirty-eight thousand died from starvation on Sumbawa and ten thousand on Lombok.8

By spring 1816 a persistent “dry fog”, which reddened and dimmed the sun, was affecting northeastern America. In Albany, New York now fell in June and did not melt, and in July and August there was lake and river ice as far south as Pennsylvania. Parts of Ireland suffered near famine conditions. Typhus, a disease associated with cold and damp, poor hygiene and louse infestations, swept through the country. Crops failed and there were violent protests in grain markets. In May 1816, riots broke out in Norfolk, Suffolk, Huntingdon and Cambridge. Threshing machines, barns and grain sheds were destroyed. Groups of rioters armed with heavy sticks studded with iron spikes and carrying flags proclaiming “Bread or Blood” roamed the countryside. In Europe, already suffering from the destruction wrought by the Napoleonic Wars, the devastation was appalling.

This was the Year Without a Summer, sometimes known as the Poverty Year.

In Switzerland the continuous summer rainfall forced Mary Shelley, John William Polidori, Byron and their friends to stay indoors and compete to write scary stories. Shelley came up with Frankenstein and Byron with the bones of a story Polidori later wrote as The Vampyre, a precursor to Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

The abnormal weather conditions continued through the winter and into the summer of 1817, when sixteen-year-old heiress Maria Glenn went to live with a yeoman farming family in Taunton. How much did the weather affect her fate…?

- The Times, 24 June 1812.

- Martin, R. Montgomery (1838), History of the West Indies, Vol. 5. London: Gilbert and Rivington. This account appears to rely on the uncredited diaries of Hugh P. Keane, now in the collection of the Virginia Historical Society.

- Nuttli, Otto W. Earthquake Information Bulletin, 6 (2), March–April 1974.

- The British colonial powers used this term to distinguish ‘Black Caribs’ from the ‘Yellow Carib’ and ‘Red Carib’ people, who had not intermixed with Africans.

- Hulme, P. Travel, Ethnography, Transculturation: St Vincent in the 1790s. Paper presented at the conference Contextualizing the Caribbean: New Approaches in an Era of Globalization. University of Miami, Coral Gables, September 2000.

- Higman, B. W. (1997). Slave Populations of the British Caribbean, 1807–1834. University of the West Indies Press.

- The diaries of James Williamson have been transcripted and are available on the National Maritime Museum Cornwall website.

- Oppenheimer, Clive (2003). Climatic, environmental and human consequences of the largest known historic eruption: Tambora volcano (Indonesia) 1815. Progress in Physical Geography, 27 (2), pp. 230–259.

Leave a Reply