In early 1814, Sarah Chandler, a 35-year-old1 sheep-farmer’s wife in the tiny hamlet of the Dolley, near Presteigne, Radnorshire, was at her wits end. She knew that if she asked her husband for money for the children’s shoes he would beat her. There was no alternative. She had to create some money of her own.

Sarah was illiterate but not stupid and planned her crime carefully. First she had asked a neighbour to write the words FIVE and TWO for her, which she then took to a local printer to print up to the correct size. After the sheets were delivered, she cut out the words and pasted them over three one pound notes from the local Kington and Radnorshire Bank. Then she and her servant went shopping, passing the notes off to traders and market stall holders.

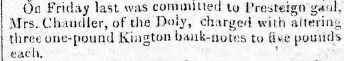

As it turned out, Sarah was easily caught and soon found herself indicted by the Grand Jury at Presteigne on forgery charges, prosecuted by the injured party, the bank, for counterfeiting banknotes. They were capital offences. By 18 March she had been committed to the stinking, rat-infested basement cells under the courthouse at Presteigne to await her trial at the assizes in April. 2

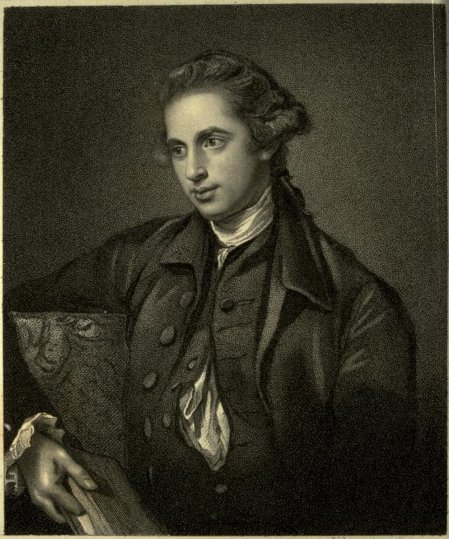

Sarah and her family would have been dismayed to find that her judge was to be George Hardinge, a well known hardliner who, ten years previously, had refused to respite 17-year-old Mary Morgan. This desperate young girl, who was employed as a cook for local gentry, had killed her illegitimate newborn child and Hardinge pounced on her conviction to make a point to any other female who found herself in the same situation. While weeping copiously, Hardinge sentenced Mary to death and then, in an especially repugnant display of sentiment, wept over her grave every time he visited Presteigne.

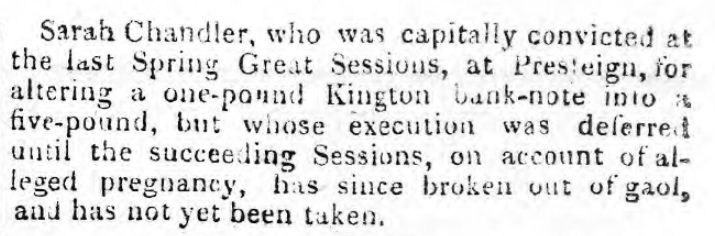

Unsurprisingly Sarah was found guilty and, of course, the sentence was death. Her only recourse now was to “plead her belly” – to claim she was pregnant – in order to delay the date of her execution while others industriously petitioned for reprieve on her behalf. Her husband appealed for mercy, as did others, including the high sheriff of Radnor Charles Humphreys Price, members of the Grand Jury, and even James Davies, the banker she had sought to defraud; there were also pleas from prosecutors and principal magistrates for Radnorshire.

The grounds the petitioners presented were many: the prisoner was illiterate, had several young children under 10, was pregnant with another, had behaved well since her arrest; the act under which she was prosecuted had only recently been passed, and her husband was respectable and honest but had deprived her of money and treated her with cruelty.

Hardinge was intractable, claiming in a letter to the Home Secretary Lord Sidmouth in June 1814 that “capital punishment for Sarah Chandler is indispensable to public justice and mercy” and that her execution would serve as a warning to others. Fraud and forgery of banknotes was a persistent problem, particularly for the Bank of England, who had a reputation for harshness in pursuing currency criminals.

Sidmouth did grant a 14-day stay for further consideration but Hardinge argued that “respite may induce unless explained a misconception of hope for her life, hopes which I apprehend your Lordship will find it will be impossible to realize.”3

When it was clear that Sarah was not pregnant, the date of her execution was confirmed for August.

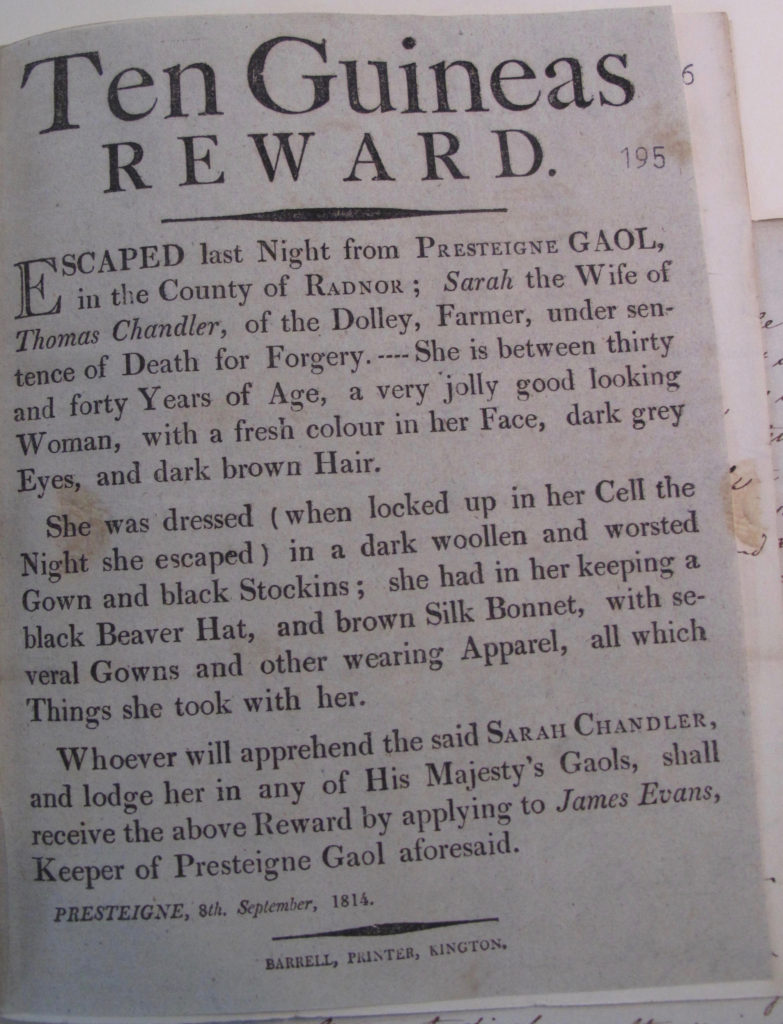

Sarah’s family were not prepared to accept this, and her brothers Francis and William Bowen took the bold decision to spring her from jail. Although Sarah was known as a respectable woman, the Bowens of Beguildy were notorious in the area for their criminality.

Nearly twenty years later, the Hereford Journal, prompted by recent convictions of Bowen family members for sheep-stealing and violence, revisited the events of 1816 by interviewing “an inhabitant of Presteign, [sic] who had personal cognizance of the facts.” He or she told the paper that “one very windy night” Sarah Chandler’s brothers, had placed a long ladder against the back wall of the jail and let down “some of the party” into the court. They then silently removed the hearthstone leading down to the condemned cell, assisted her to climb up the wall and over the ladder. On the face of it, it was unlikely that they were able to do this without some inside assistance or at least an agreement to “look the other way.”

Charles Humphreys Price later noted that the jail was “a very old building and ill constructed for the purpose intended”. The sheriff and the gaoler had reward handbills printed offering 20 guineas and 10 guineas respectively and describing her as a “jolly looking woman”. Arguably, the people of Presteigne did not try hard to find her and for the next two years there was no sign of her.

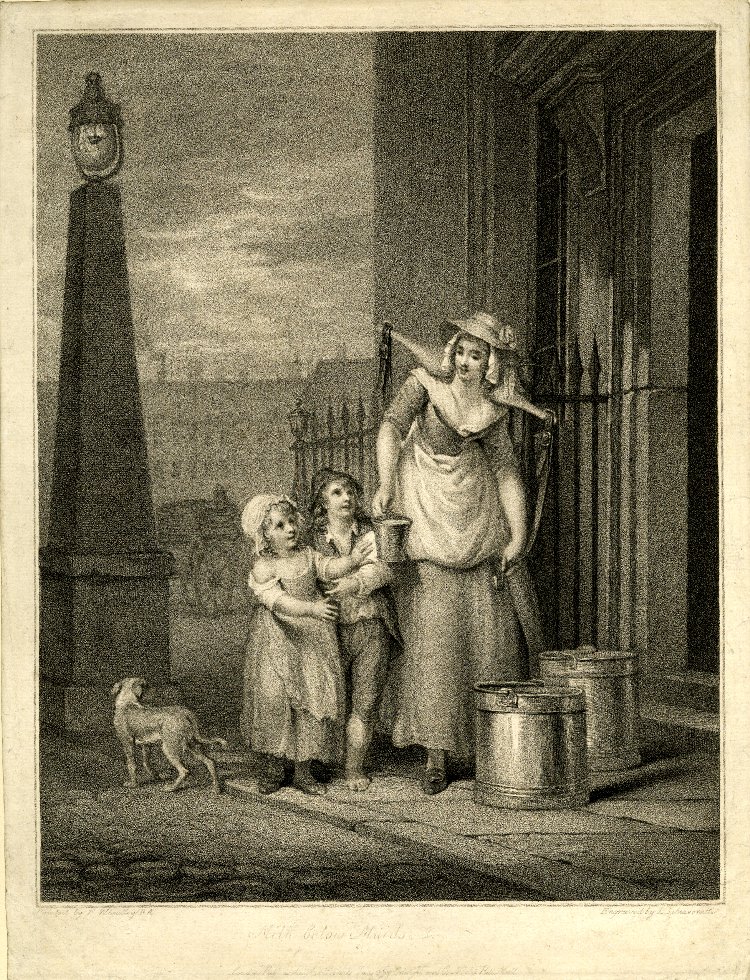

That was until late 1816 when Sarah was discovered living Birmingham, making a living by selling milk. It is unclear whether she had her children with her, but a later appeal for mercy cited the fact that she worked hard and had maintained well her large family.4

Sarah’s good fortune, if you can call it that, was that Hardinge had died in April (at Presteigne) and was no longer around to insist that she should be judicially destroyed. Her death sentence was commuted to transportation for life. In June 1817 she was with 100 other prisoners on the Friendship, bound for New South Wales, where she arrived in 1818. She was assigned to the newly opened “female factory” at Parramatta,5 an institution with many roles: prison, workhouse, lying-in hospital and refuge. In February 1819, along with 100 male and two female prisoners she was sent on the Lady Nelson to the convict settlement at Newcastle.6

Alas, back in Wales, Sarah’s family did not fare well. In 1824, aged 20, her son Peter was sentenced to two months in prison for stealing and the following year condemned to death for stealing from a dwelling house, commuted to transportation for life. He sailed for Australia on the Justicia in May 1825.7. In April 1845, the Hereford Journal noted that another son, 36-year-old Richard Chandler, had been convicted of larceny in July the previous year and transported for 10 years, and that Sarah’s brothers Francis and William Bowen were currently in prison for assault and that her sister-in-law Ann Bowen and her son Francis Bowen had just been found guilty of stealing a wether sheep and sentenced to 10 years’ transportation.

POSTSCRIPT

Sarah’s husband Thomas, described as a labourer, died in the General Infirmary at Hereford in December 1866.8

In 1823 Newcastle was cleared of convicts. How Sarah lived the rest of her life thereafter, and whether she saw either of her two transported sons in Australia, is unknown.

Updated 14 October 2017

- Estimation.

- The courthouse was rebuilt in 1826 but the cells were retained. For her idiosyncratic book on Mary Morgan‘s case, The Morning of Her Day, Jennifer Green visited the cells at Presteigne, which she describes as dark and filthy.

- Quoted in John Barrell, “The Australian Convicts of Radnorshire”, in Radnorshire Society Transactions, Vol. 60 (1990), p27-35

- National Archive HO 47/53/20.

- HO 10; Piece: 19.

- NRS 937; Reel or Fiche Numbers: Reels 6004-6016.

- Convict Prison Hulks: Registers and Letter Books; Class: HO9; Piece: 4.

- England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966. (Tentative identification).

Lovely post thank you. Sarah’s ship Friendship called in to StHelena Oct1817 while Napoleon was there, tho doubt she saw him!

How fascinating! Thanks, Lally.

I am interested to know where you found that information.

Naomi

For the past year or so I have been researching the 101 female convicts who embarked on the Friendship which sailed from England in July 1817. The literally larger than life Sarah Chandler was one of the more ‘interesting’ of the women.

Briefly – after her stint at Newcastle she returned to Sydney, spent more time in the Parramatta Factory, was assigned to Philip Parker King but in 1822 found herself on another vessel, this time bound for Port Macquarie, for stealing from her master. Having completed her time there she returned to Sydney where, at the stated age of 48!, in 1827 she married one Dennis Morrow, a 60 year old convict who had arrived on the Archduke Charles in 1813 , but who by 1827 was a ticket-if-leave man. Sarah died age 69 and was buried on 6 September 1835 at Parramatta.

Dear Naomi,

I live at Whitehall right in the middle of Presteigne in a house once occupied after 1841 by Thomas Beaumont who was, I am told (orally by Keith Parker who wrote “A History of Presteigne”), the Constable who arrested Sarah Chandler in Knighton (or possibly Kington) on the charge of forgery. By the time he got her back to Presteigne, he could not get into the gaol so he detained her until morning in a room in his house (at that time on the corner of Hereford Street and Harper’s Lane) securing the door with rope. He seems to have been quite a colourful character as he was involved in a bare-knuckle prize fight, which went on for over 40 rounds, in Presteigne in 1814 – not long after he had arrested Sarah.

Beaumont, who was a maltster, subsequently became Bailiff and sent a petition on behalf of the town to the King about parliamentary representation.

Does anyone know who, in those days, appointed Constables and Bailiffs?

Of all the characters I have encountered during my research, Sarah Chandler is probably my favourite, so this is especially interesting to me. As for your question, my understanding is magistrates appointed constables, and the bailiff was the servant of the Court leet, responsible for ensuring that the decisions of the court were enacted. The Court leet itself was a manorial court, a leftover from medieval days. Happy to be corrected as this is not something I have any special knowledge of.

Nice to see this blog still happening and the new entries. You can’t imagine how thrilling this all is as my mothers relatives were these Bowens. Francis was ggggf . His children and future off spring all had a Francis as a son they are buried in Woodend cemetery Victoria Australia.

This is great information, I am a direct descendant of Sarah Bowen Chandler – and my surname is still the Chandler name carried on from Sarah’s first husband. She had a grandson who who later migrated to Australia (Fremantle). Thanks for all your hard work with researching so people can better understand history! I realised she was a little older than me when she was shipped off to Australia.