This is a convoluted story, of two sets of murders in a small area of Norfolk within a couple of years. The killings had several unusual factors: one was that the murderers were female; another was that one set of deaths involved a murderous duo, of female friends rather than lovers (although the plot involves the lover of one of them); another was that the murderers used poison, argued to be the female murderers’ weapon of choice (we’ll come to that in Part 2); and finally, a ‘witch’, the same ‘witch’, played a role in both narratives.

We’ll start with the story of Mary Ann Wright (née Darby), who was born in 1803 in the tiny north Norfolk village of Wighton, which lies between Walsingham to the south and Wells Next the Sea to the North. In 1829, aged 26, she married William Wright, a 34-year-old “teamerman”, whose job was to deliver carts of grain pulled by five horses.1

Mary and William lived in Wighton, with Mary’s father Richard Darby. They were poor, illiterate people and they lived physically tough lives, but village life was close-knit and stable. Everyone knew everyone else.

The couple had children but it difficult to say with certainty how many. There are records for Samuel, born in 1829, but reports of Mary’s trial mention two children.

It was well known that Mary suffered poor mental health. She had been affected both by the death in March 1832 of Samuel, at the age of three,2 and another child. One person said in court that Mary was “never in her right mind” after the birth of her last child, so postpartum psychosis is a possibility. It was also assumed by her neighbours that a heredity factor played a part: her mother had spent 18 months in the asylum. Her neighbours noted that she had been behaving oddly, for example setting fire to the tablecloth and the chairs in her house.

Mary’s illness appears to have manifested itself as pathological jealousy. She told a friend that she would “stick a knife in him [William]” if he gave part of the fish he had just bought to her perceived rival and told another that she would not mind “running a knife” through him or “doing his business in some other way.” After she was arrested, magistrates heard evidence that she had made previous attempts on his life and on her own.3

Mary’s threats, and even her efforts, to kill William were brushed off at the time. No one could envisage what happened next. Mary was becoming increasingly desperate and had visited the local “cunning woman”, Hannah Shorten, at Wells, a walk of some two and a half miles. Shorten, whose services would have included casting love spells, creating charms and telling fortunes, made her living by offering magic to people for whom the Church’s teachings had little appeal. Many in poor rural societies preferred the power of folk remedies and curses; they must have seemed more direct ways to reach, and destroy, your enemies than prayer. One of Shorten’s methods for achieving your desires was to burn arsenic with salt. Whether she encouraged Mary to use arsenic in other ways, or whether Mary misinterpreted her advice, is not known.

Arsenic was a cheap poison used commonly for the killing of vermin. Thruppence (3d) would buy you three ounces, but you only needed enough to cover the tip of a knife to kill someone. It looked innocuous and could be hidden in flour or bread, or cakes. It was also tasteless but could produce a burning sensation after it was ingested. If you were intent on murder, the challenge was to acquire and administer it without attracting suspicion. As the symptoms of arsenic poisoning sometimes resembled gastroenteritis, it is likely that many poisoners “got away with it”. Vomiting, diarrhoea and inflammation of the stomach and bowels were easily mistaken for signs of cholera.

Mary appears to have planned the murder carefully. She asked Sarah Hastings to come with her on a shopping trip to Wells Next the Sea and told her that the local rat catcher had asked her to get some arsenic. Unfortunately, during the journey she quizzed Sarah on how much it would take to kill a person, something Hastings later described in court. While the women were in Wells Mary also bought currants. She said she was planning to make a plum cake.4

A few days later, on the morning of Saturday 1 December, William Wright rose early. He had been instructed by his employer to take a load of corn to Cley, just over 10 miles from Wighton. Mary gave him two plum cakes for the journey. After preparing the waggon with the help of Richard Darby, his father-in-law, and before he started out on the road, they repaired to a public house for a pot of beer and to eat the cakes. Richard returned home and William went on towards Cley with another farm worker, William Hales. He seemed fine at first but later became so ill and was in such agony, lying on sacks on the floor and unable to move, that he could not make the return journey. Instead, Hales took the team back to Wighton and Wright was carried to a public house where Charles Buck, the local surgeon, examined him. Mary was sent for. William finally expired on Sunday night, less than 48 hours after eating the cakes. Everyone, except Mary of course, blamed cholera and was terrified.5

When Mary returned to Wighton, she found that her father had also died.6

The trouble with poison, especially in food, is that you could not be sure the wrong people will consume it. Both men were buried at Wighton Church on 4 December 1832.

It was a chance remark by Sarah Hastings that Mary had recently bought arsenic which led to suspicion falling on her. Four days after the funerals, the bodies were dug up and examined by Charles Buck in the chancel of Wighton Church; the stomachs were sent to Mr Bell, a chemist at Wells, who found they contained raisins from the plum cake. Bell used four separate tests to establish that they also contained arsenic.

Mary was arrested 16 miles from Wighton, at Oulton, and appeared at a special sitting of local magistrates. She was hardly able to speak and remained almost completely silent thereafter. Shortly afterwards, she was committed to Walsingham Prison for trial at the Lent Assizes.

A decision was made to prosecute her only for the murder of her husband, possibly because it was felt that she had not intended the death of her father. The Norfolk Chronicle7 reported that she had made a full confession before she left Walsingham for Norwich Castle but she nevertheless pleaded not guilty to murder at her trial before Judge Baron Bolland. Witnesses from Wighton testified to William Wright’s sudden illness and Mary’s expedition to buy arsenic; Charles Buck described William’s death and Mr Bell his chemical tests. Mr Crosse, a surgeon from Norwich, declared that

…child bearing is apt to produce insanity [but] insanity from child bearing is mostly temporary.

Hannah Shorten was not called as a witness.

Mary was found guilty and condemned to death, her body to be buried in the precincts of Norwich Castle. She then had what was described as an “hysteric fit” after which she declared she was pregnant. After some delay, Bolland assembled a panel of 12 matrons to examine Mary and after an hour they returned to court to declare that she was not with child. Perhaps prompted by Mary’s vehemence, Bolland then asked the opinion of three “eminent accoucheurs”, including Mr Crosse, who declared that Mary was indeed expecting a child. Five months later, on 11 July, Mary gave birth to a girl, Elizabeth.8 and Mary would not have been surprised to learn that her execution was then scheduled, for 17 August.9 However, at some point before this date, her sentence was commuted to transportation for life.

Mary did not reach Australia. She died in Norwich Castle in November. Cause of death: “by the visitation of God”,10 meaning no one knew why she died. Did a brain tumour or other natural disease affect her personality and eventually cause her death? Was her death a suicide? Or perhaps the double loss of her babies, combined with postpartum psychosis, caused some aberration of mind that lead to extreme jealousy and destructive behaviour. We cannot know. The newspaper reports of her trial imply that a kind of medical defence was made but this was not spelled out and it was not strong enough to save her from a death sentence.

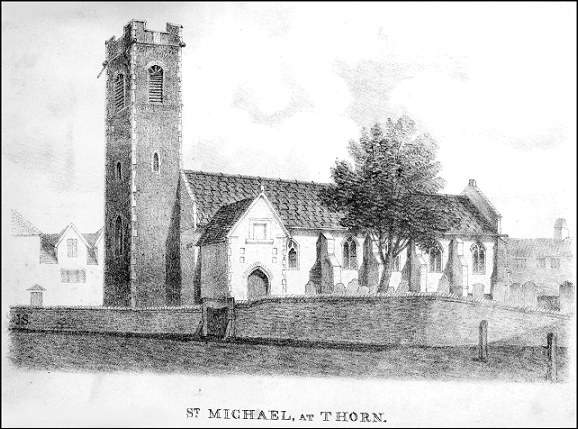

Mary was buried at the Church of St Michael at Thorn in Norfolk.11

I have tried to find out the fate of her child but have so far been unsuccessful.

UPDATES

15 November 2017

Martin York informs me that Mary’s other, unnamed child was Ellis (baptised at Wighton in 1830). He and his sister Elizabeth are found on the 1841 census living with agricultural labourer Absalom Bone at Swanton Morley in Norfolk. He married Mary Wought at Aylesham in 1855. On the 1861 census Ellis and Mary are listed as living at Reepham with three children, Ellis working as a carter; on the 1871 census he is a bricklayer’s labourer living at Cawston.

27 April 2019

Betsy tells me that Absalom Bone was her 2 x great-grandfather. His parents were Thomas Bone and his mother was Mary Wright (who was a relative of William Wright), who were married at Swanton Abb, Norfolk on 15 June 1818.

In Part 2 I’ll explore the extraordinary events of 1835 in Burnham Market, less than 10 miles from Wighton. Hannah Shorten features again.

- “Teamerman” is a specifically Norfolk term, referring to the ploughman who ran a system of alternating horses to plough fields and to the waggoner who used a team of five horses to pull carts of grain. Naomi Riches, in her book The Agricultural Revolution in Norfolk (Routledge, 1937), has a detailed explanation.

- Samuel was buried at Wighton Church. I could not find records for any other child born to the couple.

- Norfolk Chronicle, 15 December 1832.

- Plum cake contained raisins rather than plums.

- Norfolk Chronicle, 15 December 1832.

- Hereford Times, 29 December 1832, quoting Suffolk Chronicle.

- 30 March 1833.

- Norfolk Chronicle, 20 July 1833.

- Huntingdon, Bedford and Peterborough Gazette, 10 August 1833.

- London Evening Standard, 6 November 1833.

- The church, in central Norwich, was destroyed in the Blitz.

I really enjoyed reading this post especially as the Sarah Hastings mentioned in it is my 4th great aunt. My 4th great grandmother Mary Hastings nee Read is mentioned in the trial too; Mary Wright borrowed 6d off her, perhaps to buy the arsenic…

Hi my name is Lorraine wright I’m the 2x greatgranddaughter of ellis wright the son of Mary wright I moved to wighton 1991 were I started researching my wright family tree and was surprised to discover they originated from wighton, even more shocked finding out about Mary’s demise. im now trying to find what happened to the baby elizabeth if anyone has got any information on her and would be happy to share it with me I would be very greatfull

Regards lorraine

Hi I wonder if we may be related, my father was a wright, and all the family came from Wighton.

I have just read this story as I work in the Chemist in Burnham Market that although not stated here, the chemist poison record show that our chemist sold the arsenic that Mary used in the plum cake! I have worked in the chemist for ten years but have never looked up the story until today when a customer came in and I said about the murder! My boss the late Mr Brian Symonds often said about the story but I had never looked it up.

Quite intriguing!!

That is amazing, Karen. Are the records still on the chemists premises? The whole story is very sad and intriguing.

I visited the churchyard a couple of years ago to look for the gravestones of the victims, but undergrowth and building materials made it a futile search. The church was undergoing restoration at the time. Has anyone ever seen them?

I have just found out this information after researching my family history. Mary Read as my 5th great Grandmother! I can’t wait to tell my Grandma about this story!