In my last blogpost, I told the story of Mary Wright from Wighton in Norfolk, who in 1832 consulted Hannah Shorten, a local “cunning woman” or “witch” before she decided to poison her husband William by putting arsenic in a plum cake. Mary was suffering from a pathological jealousy, and it is possible that Shorten encouraged her into her actions (which also accidentally killed Mary’s father) although we have no proof of this and Shorten was not called to appear at Mary’s trial.

Two years later, however, Shorten appeared as a witness at a double murder trial, again featuring poison, at the Norwich Assizes. The deaths occurred in the Burnham Westgate (now known as Burnham Market), which lies a mile from the north Norfolk coast and five miles from Wells Next the Sea. The inhabitants of a row of three terraced cottages in North Street were involved.

Frances (or Fanny) Billing, her husband James and eight children, the youngest of whom was eight, lived in the cottage at one end; Peter Taylor and his wife Mary, who were childless, were in the middle; and Catherine Frarey, her husband Robert and their three children rented rooms above Thomas Wake’s carpenters shop, at the other end.

Washerwoman Fanny was a steady sort, a church-goer who regularly took communion. She was described later by a reporter as a “woman of no ordinary endowments,” the meaning of which is unclear, but the writer also noted her resilience and firmness of purpose, so perhaps it was her character he was commenting on rather than her appearance. Her husband James was an agricultural labourer. Like Mary Wright and her husband, and their neighbours, these were very poor people living as steadily and respectably as they could without benefit of education.

The Billings’ neighbour Peter Taylor was a journeyman shoemaker but he had suffered ill health and now worked as a sometime barber, pub waiter and singer. His wife Mary was a shoebinder. As is often the way with tight-knit groups of people living close by, close relationships can arise, and around 1834 Peter Taylor and Fanny Billing started an affair, which soon became the subject of gossip in their small community. James Billing became aware of it and, enraged when he discovered the two in close conversation out at the shared privy, beat them both. Fanny later had James arrested and bound over to keep the peace at the local Petty Sessions.

Like Fanny Billings, childminder Catherine (Kate) Frarey, aged about 46, had once had a good name but there were now rumours about her relationship with a Mr Gridley. She was known to associate with fortune-tellers and witches. Her husband Robert, once a fisherman, was now an agricultural labourer. On 21 February, Elizabeth Southgate, whose baby daughter Harriet was minded by Kate Frarey, was told that her child was very ill. At the house, she found her baby in great distress and Robert Frarey, who had been ill for two weeks, groaning in agony in his bed. Elizabeth gave Harriet a drink of warm water sweetened with sugar but she expired in the early hours of the following morning. A doctor determined that she died of natural causes.

In the days that followed, Robert Frarey showed no sign of improvement, but his wife Kate and her friend Fanny Billing were seen often together whispering with Hannah Shorten, who arrived on the day of baby Southgate’s funeral.

During this visit Shorten went with Kate Frarey to see Fanny Billing, who gave her some pennies and asked her to get some white arsenic to kill mice and rates. There is some question over whether it was Shorten or Billing who went to the pharmacy with Frarey, but whoever did the purchasing, the result was that a quantity of arsenic was bought.

Shortly afterwards, Elizabeth Southgate came to enquire about Robert Frarey’s health. In court she described Fanny Billing offering her porter, which she had poured into a teacup. Elizabeth saw sediment in it and handed it back saying, “I should not take sugar in porter.” Her suspicions were growing but whether or not she guessed the truth at this stage, it was a wise move. Billing handed the drink to Robert Frarey, saying, “Drink it up. It will do you good.” When Northgate returned that evening, Robert was retching violently into a basin, after which he deteriorated quickly and 48 hours later, on 27 February, while Elizabeth was visiting once more, he died. His wife and Fanny Billing were attending him. He was buried shortly afterwards at St Mary’s in Burnham Market.

Gossip must have started immediately. On a trip to Wells with Kate Frarey some time after the funeral, Elizabeth Southgate talked to her about the cause of Robert’s demise:

“If I were you, Mrs Frarey, I would have my husband taken up [disinterred] and examined, to shut the world’s mouth.”

“Oh, no,” she replied, “I should not like it. Would you?”

“Yes, Mrs Frarey, I would like it, for it will be a check on you and your children after you.”

Westgate St Mary

© Copyright Colin Smith and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

Barely a week after Robert Frarey was put in the ground, Fanny Billing was persuading a neighbour to accompany her to buy arsenic, saying it was for a Mrs Webster (who later denied all knowledge). Inspired by the successful despatch of Robert, Fanny and Kate were now determined on a new victim: Mary Taylor, whose husband Peter was having an affair with Fanny.

With the arsenic bought, all that was needed was opportunity. On 12 March, while Mary Taylor was out at work, Billing or Frarey or Peter Taylor, or perhaps some of them in combination, poisoned the dumplings and gravy she had left out for the evening’s supper. When Mary fell ill, she had the misfortune to be nursed by Kate Frarey. People came and went, and neither Frarey nor Billing seem to have been too guarded in what they did nor said while they did so. William Powell, the village blacksmith, stopped by for a haircut and shave. He saw Kate Frarey bring in a bowl of gruel and, using the tip of a knife, add to it what looked like powdered sugar. Phoebe Taylor, married to Peter Taylor’s brother, visited to tend to Mary and care for Peter. She saw Fanny Billing take a paper out of her pocket and pour its contents into a teacup, throwing the paper in the fire.

Eventually, with Mary in convulsions, Phoebe Taylor and Kate Frarey summoned a doctor. He found that Mary’s pulse was feeble and she died in his presence.

A coroner’s inquest was ordered, and Mary Taylor’s body was opened in her own kitchen. Her stomach was taken to the pharmacist in Burnham Market, where it was found to be riddled with arsenic. Next it was taken to Norwich where more tests were conducted by surgeon Richard Griffin, again confirming arsenic.

The atmosphere in Burnham Market must have been febrile, when James Billing, who was already on the alert, in an unguarded moment, accepted a cup of tea from his wife. He became very ill, but recovered.

Fanny Billing was arrested on 18 March and taken to Walsingham Gaol. Kate Frarey then asked Fanny’s sons to drive her to Salle, “to see a woman there who is something of a witch [not Shorten], that that woman might tie Mr Curtis’s tongue so that he might not question my mother.” Mr Curtis was the gaolkeeper at Walsingham. Fanny’s sons questioned why, if their mother was innocent, Frarey should wish this. The indiscreet comments did not stop. When Peter Taylor was arrested, Frarey shouted out to him, “There you go, Peter, hold your own, and they can’t hurt you.” There were numerous other examples.

Kate Frarey and Hannah Shorten were also arrested and Robert Frarey’s and Harriet Southhgate’s graves opened. Peter Taylor’s house was searched for signs of arsenic. All three suspects, Billing, Frarey and Taylor were committed for trial at the Lent Assizes at Norwich, but charges against Shorten did not stick. Taylor escaped when the grand jury chose to “ignore” his indictment as an accessory before the fact.1

In a packed courtroom on 7 August, appearing before Justice Bolland, Frarey and Billing were both found guilty of both murders (no discernable traces of arsenic were found in baby Southgate’s body). As he condemned them to death, the judge referred to the women’s “profligate, vicious and abandoned course of life”, full of “guilty lusts”. He urged them towards repentance and sincere contrition and ordered their bodies to be buried within the confines of Norwich Castle.

Kate Frarey, often agitated, needed support. She went into “strong hysterics” and her shrieks could be heard after she was removed from court. Billing was more stalwart, and showed no emotion as the verdicts and sentence were given.

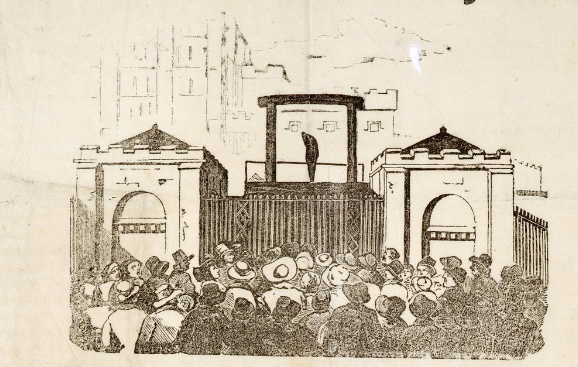

The women’s execution on 10 August attracted vast crowds into Norwich from the surrounding villages. All routes leading to the castle were thronged with “persons of various ages and of both sexes (the weaker vessels being the more numerous)”.2

To reduce the distance the women would have to walk to the gallows, the apparatus was moved to the upper end of the bridge, which also had the effect that more people were able to see the action. At 12noon the great gates opened and the Rev James Brown, prayer book in hand, followed by “the two unfortunate beings”, Frarey dressed in mourning for her husband and Billing in a “coloured clothes”, white handkerchiefs covering their faces emerged for their last journey. Billing walked with “a firm step”, but Frarey was on the point of fainting and had to be carried up the steps of the scaffold. The executioner William Calcraft was in attendance.

The Norfolk Chronicle described the scene:

It was a sight which no one, but an alien to humanity, could look on unmoved.

After the ropes were adjusted, hooded and holding each other by the hand, the friends dropped and were “launched into eternity”. Frarey was “much convulsed” but Billing’s neck broke and she suffered less.

The crowd was silent.

Peter Taylor, who escaped trial, was among the spectators but was forced to flee when the crowd turned on him. He managed to make it his home village of Whissonsett but he was not safe. Before their executions, the women had made fulsome confessions, implicating him, if not of being directly involved at least of knowing what they were doing. The investigation was reopened and on 29 August, scarcely three weeks after Frarey and Billing had been executed, he was committed for trial as an accessory before the fact to his wife’s murder. He was found guilty and, insisting on his innocence to the last (which meant that he was denied the sacrament), in “a state of the greatest prostration of strength, both mental and corporeal,” on 23 April 1836 was executed at Norwich Castle.

Serial poisoning is generally a solitary crime, characterised by subterfuge and secret triumph over the victims. It is not often conducted in pairs or trios, which makes Billing and Frarey (with or without Peter Taylor) so unusual. It is noteworthy that they were unable to keep quiet at the appropriate times and talked unguardedly, raising suspicion and indeed certainty of what they were doing. Even if they had other victims, and there was plenty of speculation that they did, they were, in the end, singularly unsuccessful in getting away with their crimes undetected, precisely because they could not keep their mouths shut.

Billing and Frarey were also unusual because they were women. Although they committed the murders at the start of a run of female poisoners, which culminated in the so-called poisoning panic of the 1840s, and despite the general feeling that poisoning was a female crime, the truth is that poisoning is more likely to be committed by men. When the victim is female, the perpetrator is significantly more likely to be male; when the victim is male, the poisoner is equally likely to be male or female.

Perhaps the perception of poisoning as a female crime arose from the fact that when women did choose to murder, which was rare enough in itself, poisoning was often their weapon of choice. Female murderers did not often use brute force to kill their victims (unless, of course, those victims were smaller and weaker: children and newborn babies). Women tended to deliver their killer blows using the medium that was most available and most effective: food, laced with poison, generally arsenic. Perhaps that accounts for the poisoning panic: as the judge at Frarey and Billing’s trials said, poison “was one of the worst acts that can be resorted to, because it is impossible to be guarded against such a determination, which is but too often carried into effect, when no one is present to observe it but the eye of God.”

There must have been numerous cases in history where women’s efforts to drastically change their lives by ending someone else’s (most often their husband’s) by putting arsenic in their food went entirely undetected because these women had cooler heads and operated on their own. Frarey and Billing were astonishingly obvious. Perhaps they encouraged by Shorten and her like to think that what they were doing had magical qualities or that their friends and neighbours trusted them so much that they would not begin to suspect them. In a world where justice was so unreliable it was fairly certain that their detection and punishment would follow.

Stuff of Dreams theatre company toured with a play, written by Cordelia Spence and Tim Lane, based on Frarey and Billing. Watch the trailer: nice and atmospheric.

POSTSCRIPT

Hannah Shorten is found, aged 80, in the 1851 census, living in Wells and described as a pauper.

James Billing, the only spouse to survive, died in 1871, aged 84, in Alderbury, Wiltshire.

Much of the detail of the case is given in the Norfolk Chronicle, 15 August 1835.

I am indebted to Maurice Morson’s excellent account of this extraordinary story in Norfolk Mayhem and Murder, published by Wharncliffe Books (Pen & Sword), 2008. Recommended reading.

James Billing was my forebear.

He had a son John Billing – a shoe maker in Blakeney.

John’s daughter Elizabeth married John Huggins who worked for Colmans Mustard in Norwich.

My grandfather, Charles Alfred Huggins, born in Lakenham, was their middle child.

Interesting that Elizabeth Billing had a brother, William, who was a policeman in Norfolk for many years.

My late mother was surprised when we proved that her great grandfather, James Morley, born in Bury St Edmunds was sent to Australia in 1836, as a convict. He served his time for stealing the church silver from Burgate in Suffolk, and brought up his 13 children in Heidelberg and Whittlesea in Victoria, to each raise at least one child and add to the prosperity of Victoria.

I am pleased that my mother did not live to hear of this, new to us, part of her husbands heritage.

And how many of the Billings or Huggins families know the story. They were all too busy living a good, peaceful and helpful life back in 1835.

Now communications and research is so much easier we are learning about the past.

But I would also like to know why the Billing forebears moved from Cornwall to the Norfolk coast.

Thanks for your information, Margaret. Yes, it is those who hit the headlines that leave stories behind, not those quietly going about their business! As for the move from Cornwall to Norfolk, I don’t know the answer but if your ancestors were involved in coastal industries perhaps that might be an angle to look at.