I have been giving thought to the emotions women experienced after being sentenced to death, and wondering how many of them managed to keep their composure on the day.

In early 1818 the Quaker prison reformer Elizabeth Fry counselled and supported two women incarcerated in Newgate who were facing death. Mary Ann James1, who had been convicted of an easily-discovered fraud involving the sale of annuities, and Charlotte Newman, convicted of uttering a forged bank note.

On 1 November 1817 33-year-old Charlotte Newman was arrested after passing off a forged one pound note when purchasing half-boots at John Bartlett’s shop in Denmark Street in central London.2 Little did she and her companion George Mansfield realise but they had for some days been under surveillance by Samuel Plank and Charles Jeffries from the Marlborough Street police office.3. George was arrested as he loitered outside the shop and Charlotte immediately after she had completed the transaction. She told the officers that she was an ‘unfortunate woman’ (a prostitute) and that a gentleman had given her the note ‘in a coach’ but this explanation was not accepted. She also denied being with George Mansfield, but officers discovered that she and Mansfield were in possession of similar keys and they were soon both connected with a lodging house in Bunhill Row where 28 counterfeit one pound notes were found in the room that Charlotte rented. Charlotte and Mansfield were charged with uttering, a capital offence, rather than possession, which carried an automatic sentence of 14 years transportation, and locked up in Newgate to await trial.

In 1817 the Bank of England was experiencing a crescendo of low denomination note forgery.4 In 1816 over 29,000 notes had been discovered, but this was known to be only a fraction of the actual number in circulation; 120 people were prosecuted (up almost 100 per cent on 1815) at a cost of nearly £23,000. In 1817, prosecutions had climbed to 142 and costs to nearly £30,000.5

Charlotte Newman and George Mansfield appeared together at the Old Bailey on 3 December 1817. As Charlotte had been caught red-handed, there was never any real prospect of her getting off the charge. She tried to deflect blame from Mansfield, stating at the end of proceedings, ‘The other prisoner is perfectly innocent, and knows nothing of the transaction.’ The jury decided that the case against him had not been made. He was, after all, arrested outside the shop and although clearly connected with Newman he was not seen to handle the notes himself.6

For Charlotte a guilty verdict meant an automatic sentence of death. Now the only avenue left for her was to plead for mercy from the Bank, which in law had no jurisdiction over this decision. The reality, however, was that its say was almost always decisive and that it could, and did, affect the fates of thousands: the members of the Committee for Law Suits could indicate that they would not oppose a respite of sentence (a technical pardon that would allow transportation for life instead of a visit to the gallows) and their disinclination to interfere meant that capital punishment would proceed.

Mary Ann James’s crime was also forgery and the victim was also the Bank of England. Rather than bank notes, however, it concerned the fraudulent acquisition of annuities.

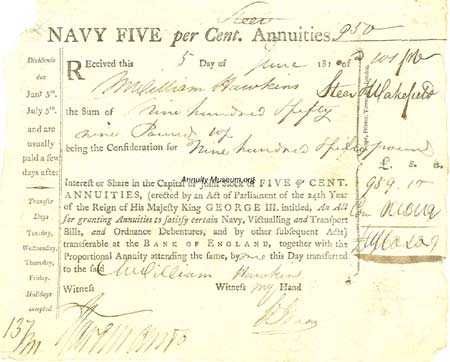

In March 1817 Elizabeth Thomas, an out-of-work servant on her way from London to Cornwall to see her mother, struck up a conversation with her young travelling companion. Miss Baker told Elizabeth she was looking for a servant herself as she was soon to be married and she arranged to meet her at Exeter in a few days time. What would make more sense than for Elizabeth to give Miss Baker her clothes and papers for safe-keeping? That was the last Elizabeth saw of her new acquaintance until they faced each other at the Old Bailey, where Miss Baker, whose real name was Mary Ann James, had been indicted on nine alternative charges, three of them capital. Mary Ann, a mere 20 years old, had sold Elizabeth’s £155 worth of shares in the Navy Five Per Cents using a fraudulent power of attorney. The deception was only discovered when Elizabeth came up to London in order to collect her dividend and was told that the stocks were no longer hers. Six weeks later Mary Ann was arrested and prosecuted by the Bank of England.

Mary Ann James appeared at the Old Bailey on 3 December 1817, the same day as Charlotte Newman and George Mansfield, represented by John Curwood.7 She claimed that she had been the dupe of a man called Goddard (an attempt to find such a person had been made, without success). However, her case was hopeless and a guilty verdict inevitable. She was condemned to death.

In Newgate, Charlotte and Mary Ann James came to the attention of Elizabeth Fry, the Quaker reformer who had made Newgate and the women in it her personal project. It was not just the horrendous conditions that women in Newgate suffered – far worse than those in the men’s wards – but also their spiritual health that interested Fry. She was an ardent opponent of the death penalty:

Does capital punishment tend to the security of the people? By no means. It hardens the hearts of men, and makes the loss of life appear light to them; and it renders life insecure, insasmuch as the law holds out, that property is of greater value than life. The wicked are consequently more often disposed to sacrifice life to obtain property.’8

Capital punishment led to a fatalism among law-breakers, and did nothing to deter crime, she wrote. Punishment should not be for revenge but to reduce crime and reform the criminal.

Charlotte probably understood that there was little chance of a reprieve at this stage. Late one evening during the week before she was due to hang, she wrote a letter addressed to the Bank of England, possibly with the assistance of Fry herself. Charlotte’s heart-rending plea is preserved in their archives:9

I most humbly hope your humanity will excuse the liberty I take to intreat your consideration of my most afflicting situation. I sometimes felt some hopes hearing of your great mercy towards those who have been allowed to plead guilty the last Sessions. I trust I feel most sensible the awful situation I am now in and the justness of my sentence. When I was at the bar my life was then in your hands and I now feel it more accutely. Let Mercy be blended with Justice. It is yet in your power to save the life of an unhappy sufferer which I most earnestly implore of you. How sweet will be the hours of reflection when you can rest upon your pillow and commune with God & yourself that life which if taken from one of God’s creatures you have not power to give. A few days, nay hours, will determine this awful event. I once more humbly beg of you to save my life. There is time yet for your consideration. All depends upon you and an all wise providence. The Just and Good God deigns to say he will pardon & receive the true penitent whose sins are as unmeasurable as the sands of the seas. His promises are we shall live with him forever. Can you then feel pleasure in the death of a fellow mortal that you are the means of saving?

I once more intreat your mercy to spare my life which will if I am allowed to hope for it be spent in the service of my offended God and prayers that you may experience every blessing he is able to bestow. From the unfortunate Charlotte Newman

Condemn Cell half past 11 O Clock at Night

Pardon me if from the impulse of the moment I have said too much.

Also in the archives is a copy of the note that was sent back by the Bank’s solicitors:

Charlotte Newman, I received your letter but I cannot interfere in your behalf. The Governor & Directors of the Bank have considered your case & they also decline to interfere. JK Westwood, New Bank Bds 13 Feb 1818

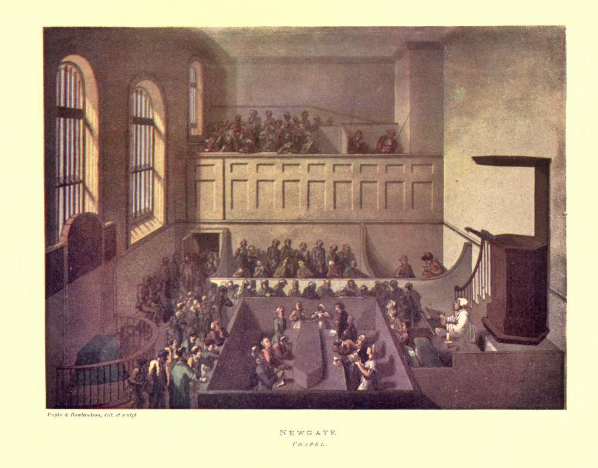

Two days later, on the Sunday before their execution, the condemned prisoners of Newgate, Charlotte, Mary Ann and two men, William Hatchman and John Attel,10 were obliged to attend Newgate chapel for the condemned sermon, given by the Ordinary, the evangelical Reverend Horace Salusbury Cotton, in which he called them to repentance. In order to add to the solemnity of the occasion, the condemned were seated in a pew around a coffin in the well of the chapel. Tickets for what was in effect a theatrical spectacle were sold to local residents and other interested parties. ‘We never saw so crowded a congregation on any occasion to hear the sermon,’ reported The Observer.11

Newgate Chapel, from Microcosm of London; or, London in miniature

Cotton was known for his abrasive style and would often scream at the condemned, threatening that they would burn in hell for eternity. The presence of two women in the condemned pew may have restrained him somewhat, although he felt it was a good idea to spell out what they faced in two days’ time. Cotton chose as his text, ‘Have pity on me, have pity on me, oh ye, my friends, for the hand of God hath touched me’12 and ‘dilated with much effect upon the necessity of a severe application to the doctrines and ordinances of God, in order that consolation might be derived, and forgiveness obtained.’ The prisoners were to suffer ‘a dreadful and ignominious death – disgraceful to themselves, disgraceful to those they leave behind,’ he said, and referred to their parents’ grey hairs ‘brought down with sorrow to the grave’ and to ‘wives made widows before their time.’ He took it upon himself to explain to the congregation the seriousness their crimes. Forgery, he said, was,

too prevalent, a crime which appears to increase with every session! and in a commercial nation like this, where public and individual credit is the vital principle of its daily transactions, perhaps it is as mischievous as any that can be committed against the commonweal; for it rudely bursts asunder the links which unit such a society in the great chain of mutual credit and confidence, and is calculated to plunge the whole into distrust and confusion.

Addressing the women directly, he spoke of the ‘big round drops rolling down your pallid cheeks – full well I hear the agonising sighs which issue from your hearts’, and of their ‘hearty contrition’ and ‘unfeigned repentance’. And he entreated Jesus Christ to number them amongst those who ‘unrighteousness is forgiven, and whose sin is covered’.

At this point, when ‘there was scarcely a dry face’ among the gathered, Cotton finished by exhorting the congregation to have pity on the condemned and ‘however they may abhor the offence, let them learn to pity the offenders’.

We trust that God will lend a gracious ear, and a complacent eye to their penitence and faith, and that they are now well on their way to heaven. Thither we all wish to go; and if God speed our progress, we shall again meet them in the presence of the glory, and unite with him in the everlasting praises before the throne.

At six o’clock in the evening before her death, Charlotte wrote to Elizabeth Fry, telling her that she had achieved a state of calmness about her impending end.

The mercies of God are boundless, and I trust through His grace this affliction is sanctified to me, and through the Saviour’s blood my sins will be washed away. I have much to be thankful for. I feel such serenity of mind and fortitude.

She thanked those who had helped her and brought her to this state of grace, including the Rev Cotton. It is possible that Elizabeth Fry herself had a hand in writing the letter.

At midnight, the sexton of the nearby St Sepulchre’s Church rang the traditional handbell outside the condemned cell and intoned the traditional verse:

All you that in the condemned hold do lie,

Prepare you, for tomorrow you shall die;

Watch all and pray: the hour is drawing near

That you before the Almighty must appear;

Examine well yourselves; in time repent,

That you may not to eternal flames be sent.

And when St Sepulchre’s bell in the morning tolls,

The Lord above have mercy on your souls.13

Mary Ann’s final letter was addressed to her fellow prisoners, and again it may have been influenced by Elizabeth Fry. She asked them, as ‘one particular favour’ to let the ‘true light of the Gospel’ into their minds. ‘I was dark when I first came into these walls, and what must you all suppose the love, the gratitude I now feel, I am going but a short time before you.’

After a night in which they hardly slept Charlotte and Mary Ann James admitted their guilt, Mary Ann claiming she had been led into it, a claim she made during her trial, and Charlotte that she had committed the crime in an effort to join her husband in Botany Bay (he had been transported for a similar offence).14

Outside Newgate an immense crowd was gathering.15 Not only was a double execution of women rare, this was the first execution in England of a woman for forgery since 7 April 1810, when Frances Thompson was hanged at York, and the first at Newgate since Mary Parnell on 13 November 1805. Shortly after eight, the Sheriff and Under Sheriffs and others arrived at the Sessions House and went first to the cell where Hatchman and Attel were confined, attended by the Rev Cotton. He ushered them into the Press Yard, where their leg irons were removed, Hatchman showing signs of distress, saying in a ‘tremulous’ voice, ‘I have seen a great deal of trouble in my time; thank God, however, it will soon be at an end; it must be an easy death.’ It did not turn out to be so.

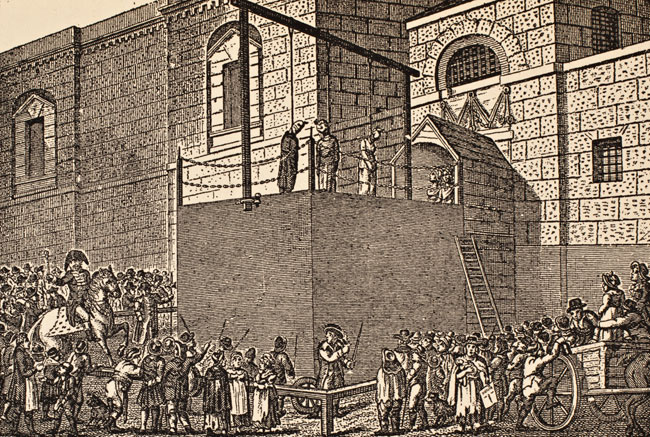

A hanging at Newgate

Executions were emotionally risky affairs. The authorities wanted them to be solemn and orderly ceremonies of high drama, from which the spectators took away a message that the pain of death was not worth the rewards of crime. But there was always a danger that feelings of sympathy amongst the crowd would cause disorder. A surge in the crowd at the 1807 Newgate execution of Owen Haggerty and John Holloway, whom many believed to be innocent, resulted in the deaths of over 30 people.

The behaviour of the condemned on the scaffold was of intense interest to the spectators and of the wider reading public. Women were praised for exemplary conduct. When Elizabeth Godfrey was hanged at Bodmin in 1813 for arson, the Royal Cornwall Gazette16 reported:

It is with pleasure we [can report] that her behaviour after condemnation was such as to afford perfect reason to hope that death was to her but the passport to eternal life.

Ann Hawlin, guilty of murdering her baby and due to hang at Warwick in 1817, was not so compliant. She ‘resisted every exertion made to convince her of the enormity of her crime, and to direct her attention to that source whence alone mercy could proceed’. Eventually, she confessed her guilt but only in a general way and when she mounted the scaffold was ‘sullen and reserved’. She ‘shrank with horror from the awful scene’. When she dropped, she was said to have been ‘convulsed for a considerable length of time’; many believed that ‘suffering’ was in direct proportion to the degree of contrition rather than the skill of the hangman.17

The Sheriff of Newgate would have been keen to avoid the type of scene that occurred in 1817, when seven people, including Elizabeth Fricker and William Kelly, went to the gallows for their part in the burglary of Elizabeth’s employer’s home. One man, Thomas Cann, had to be restrained in a straightjacket, such was the extent of his distress. Elizabeth wept and was ‘constantly more absorbed in grief than hope’. On being led to the scaffold she ‘looked wildly around upon the multitude’.

Upon the executioner proceeding to put the rope around her neck, she gazed with terror, entreated she might not be hurt, burst into a flood of tears, and asked to take leave of Kelly; the latter was immediately brought forth, and they instantly embraced, Kelly vociferating ‘she is innocent, innocent – murdered, murdered.’18

When it was their time to approach the scaffold, the resolve Charlotte Newman and Mary Ann James had shown earlier faltered and they had to be ‘supported’ on the final steps of their journey. They emerged through Debtor’s Door and climbed the scaffold, followed by the Hatchman and Attel; on the platform all four knelt in ‘fervent’ prayer. Hatchman was said to have looked into the crowd to see if he could recognise his friends and appeared anxious to say something, but didn’t. He saluted Charlotte, evidently a prearranged sign of encouragement.

The Trials and Execution of John Attel for Burglary, and William Hatchman, Charlotte Newman, and Mary Ann James for Forgery, who were Executed this Morning, before the Debtor’s Door, Old Bailey

Next the condemned were prepared for death: their arms were pinioned, hoods pulled over faces, nooses adjusted; Rev Cotton pronounced the words ‘In the midst of life we are in death’ and gave the signal, after which the four were ‘launched into eternity’.

It was a botched job. Some of the ropes, ‘especially that of Hatchman’, had been badly adjusted and caused great agony. ‘The women were deeply affected,’ reported the papers, meaning that Charlotte and Mary Ann were convulsed for longer than was usual. The crowd reacted by hissing and groaning.

At 9.30 the bodies were taken down. The families were now allowed to collect them, minus their clothes, which were the property of the executioner, who also took a fee.

The opponents of the death penalty were appalled at the waste of life. John Attel, they pointed out, was the father of four young children and his wife was heavily pregnant with another. Mary Ann James had been brought up ‘with much indulgence’ but had ‘afterwards had to pass through various afflictions and temptations’. She had fallen into bad company but her conduct in prison had been exemplary. If she had been allowed to live, she could have become a valuable member of society.

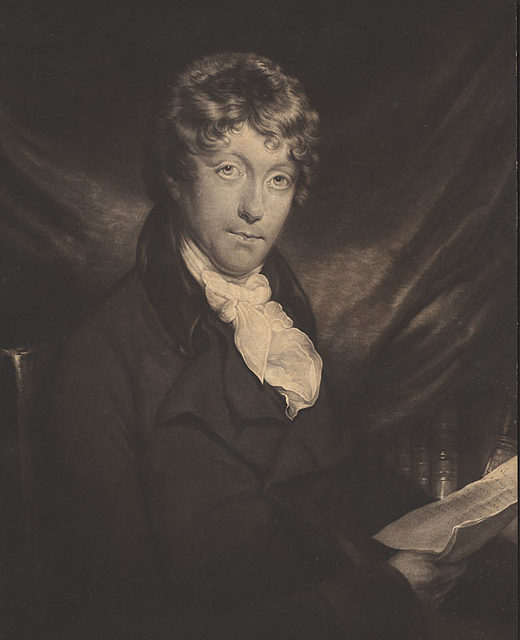

William Garrow in 1810, courtesy of Harvard University Library, olvwork178120

POSTSCRIPT

In the archives of the Bank of England is a note to the effect that the Bank would not oppose Charlotte Newman’s request to plead guilty to the lesser offence of possession. After all, a plea bargain of this kind was not uncommon. The Bank wanted a certain degree of public retribution – it was meant to deter others – but not so much as to encourage their critics. It may have been the judge, William Garrow, who insisted on the charge.

- Also known as Jones

- Off Charing Cross Road.

- Now Great Marlborough Street

- I have written elsewhere on the Restriction of 1797-1821.

- Data from Randall McGowen, ‘Managing the Gallows: The Bank of England and the Death Penalty, 1797-1821’. Law and History Review, Vol 25, No. 2 (Summer 2007), pp 241–282.

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2, 05 May 2016), December 1817, trial of CHARLOTTE NEWMAN GEORGE MANS-FIELD (t18171203-55).

- Curwood defended Arthur Thistlewood and members of the Cato Street Conspiracy in 1820.

- A memorandum amongst Fry’s papers, quoted in Memoir of the Life of Elizabeth Fry, with Extracts from Her Journals and Letters. Philadelphia: J. W. Moore (1847).

- Slight corrections for standard punctuation and spelling.

- Hatchman for forgery; Attel for burglary.

- 1 March 1818.

- Job 19: 21

- Quoted in Stephen Halliday, Newgate: London’s Prototype of Hell. The History Press (2013)

- The reports do not make it clear to whom they made these admissions; it may have been to Elizabeth Fry.

- Huntingdon, Bedford, Cambridge and Peterborough Gazette, 21 February 1818.

- 11 September 1813.

- Staffordshire Advertiser, 26 April 1817.

- Exeter Flying Post, 13 March 1817.

[…] writing this, I found this excellent article by Naomi Clifford http://www.naomiclifford.com/charlotte-newman-mary-ann-james/ My approach is slightly different, but Naomi provides excellent background research and a different […]