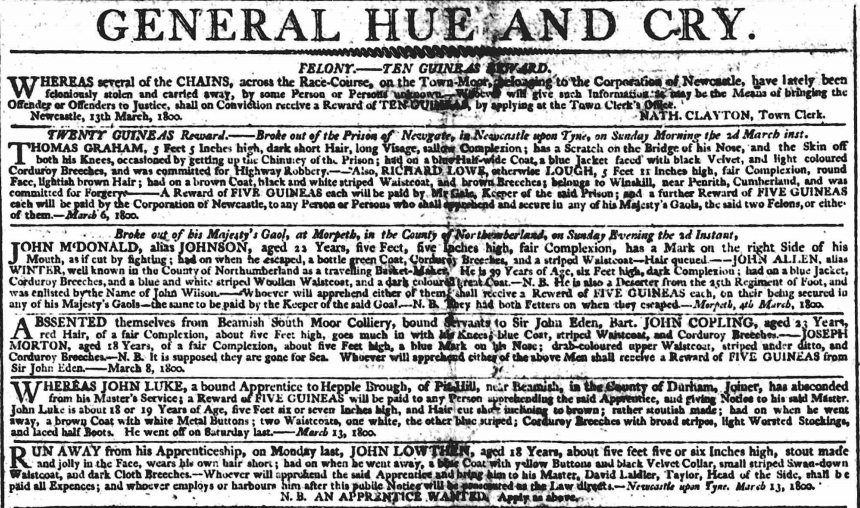

The Newcastle Courant, 15 March 1800

In 2015 I wrote about the 1816 escape of six prisoners from Newgate in 1816 (they knotted blankets together) and also of the daring exploits of bank note forger Sarah Chandler, who was sprung from Presteigne gaol in 1814 after she was sentenced to death.

I have it on good authority (my sister, who for many years was a prison officer) that while some guests of Her Majesty can’t stay out of prison and prefer it to life outside, others will do almost anything to get out and will attempt to do so even if legal release is imminent. Of course, the fact of being under (or expecting) sentence of death or of transportation would increase the motivation to leave.

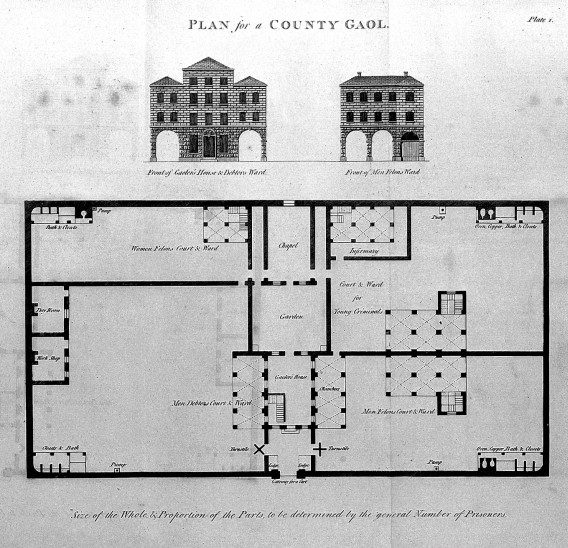

Plan for a County Gaol. From John Howard’s The state of the prisons in England and Wales, with preliminary observations, and an account of some foreign prisons and hospitals (1792) Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

The front page of The Newcastle Courant of 15 March 1800 details two escapes, the first from Newgate Prison in Newcastle Upon Tyne (there were several gaols named after the London one). Mr Gale, the keeper, offered five pounds, with the Corporation of Newcastle matching his reward, for the capture of Thomas Graham, who was charged with highway robbery, and for Richard Lowe or Lough, accused of forgery. Graham climbed up the chimney of the prison and consequently had a scratch on the bridge of his nose and grazes on his knees.

In the same paper, there’s a description of John M’Donald (alias Johnson), 22, who had a distinctive mark on the right side of his mouth “as if cut by fighting”, and John Allen (alias Winter), 39, a deserter from the 25th Regiment of Foot and formerly a travelling basket maker, who went missing from Morpeth gaol, both wearing fetters at the time, which might say something about the security, or lack of, at the prison. Five guineas was on offer for each of them.

The Old Tolbooth, Edinburgh. Via Wikipedia Commons.

A report in The Caledonian Mercury (25 May 1801) on the escape of seven convicted men from the Tolbooth in Edinburgh “by cutting the floors, and breaking through sundry divisions in the house” offers an opportunity to visualise the appearance of some of what was termed by the middle class as “the criminal classes”. I’ve picked out some details.

Andrew Holmes: A bookbinder under sentence of death for housebreaking. “Pitted with the small pox” and with a “small lisp” in his speech.

Lauchlan Love: A shoemaker likewise sentenced and also “very much pitted with the small pox”. He had “many blotches and scars on his head”.

Peter Anderson: A former militiaman, sentenced for shopbreaking. “Stout made, fair complexion.”

James Steven alias Douglas: A slater and former seaman. Wore a “blue jacket very much joined or pieced on the breast.”

John Hunter: Convicted of stealing rags. “Swarthy complexion, much pitted with the small-pox … has a large scar, as if with the scurvy, on the lower parts of his cheeks.”

William Maxwell: Former sergeant in the militia, found guilty of sedition, “swarthy complexion, much pitted with the small pox, speaks quick, and has a particular lisp, and has an uncommon rolling in his eyes when speaking.”

John Inglis: A labourer, convicted of horse stealing, six feet tall with a swarthy complexion and a round face.

They sound a rough bunch, but I suspect a good proportion of them were destitute.

Some escape attempts failed, of course. In Horsham in 1814, the would-be fugitives were betrayed by a fellow prisoner. Hannah Knight, who had been capitally convicted in 1813 at Lewes, Sussex for stealing four pound notes from a letter, was respited and her sentence commuted to transportation. During her journey to Newgate in London (from whence she was due to be taken to a ship bound for Botany Bay) she told Mr Smart, who was accompanying her, that prisoners at Horsham had skeleton keys made of pewter and that they had nearly managed to saw through their leg irons. “The men and women by the help of these keys it seems, got together at their pleasure,” reported the Sussex Advertiser.1 Hannah was rewarded with a free pardon.2

The Prisoner, Joseph Wright of Derby (1787 to 1790). Courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

The report of a 1827 escape has a wealth of detail on the method used by prisoners to escape from a “flat” [a self-contained landing] in Glasgow gaol. Using a piece of iron, they cut through the stone around the bolts on their cells and filled the holes with putty. At a prearranged time, they all opened removed the bolts and got into the lobby, and from there into the water closet where they proceeded to cut the iron bar across the frame of a window, hoping to drop down into the yard and get over the perimeter wall. Unfortunately, sturdy iron gratings had been installed on the outside of windows to stop contraband alcohol being passed in and the plan was foiled. When the turnkey entered the flat at 5am the next morning he was alarmed to find all the prisoners in the lobby, but they told him not to be afraid as they knew the game was up.3The Globe, 10, 13 April 1820.[/ref]

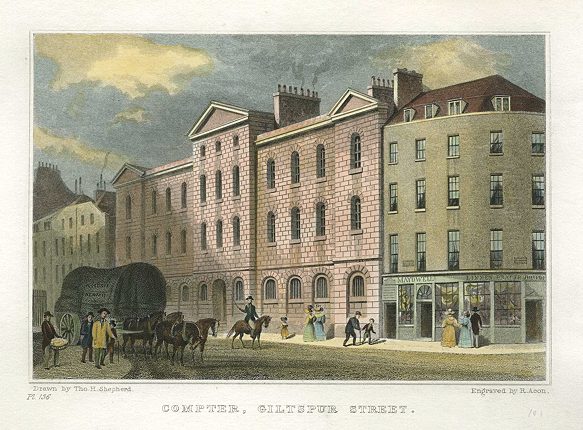

“Compter, Giltspur Street” engraved by R. Acon after a picture by T.H.Shepherd, published in London in the Nineteenth Century, 1831. Image courtesy of ancestryimages.com

Not all crims were lower class of course. In 1820 Lieutenant John Henry Davis (son of Sir John Davis), escaped from the Giltspur Steet Compter, a prison yards from Newgate, where he was awaiting examination on suspicion of a massive forgery of stocks. He simply changed into a suit of livery identical to those of his manservant and, head down, walked past the turnkey, who was ailing with arthritis at the time. Davis and his manservant Samuel Gooding had carefully planned the escape, even down to Gooding wrapping his face in a black silk handkerchief as if he had toothache so that Davis could similarly cover his face from the turnkey on exit, and arranging for a steed to be waiting in nearby Smithfield. On this Davis zoomed off to Croydon, jumped into a chaise and four and headed for Brighton where a boat took him to France. He is thought to have ended up in America. The servant got six months in prison and the turnkey was suspended from duty.4

Not included here are the exploits of smuggler, adventurer and inveterate escaper Tom Johnson (or Johnstone), who deserves a post (or a biography) all of his own.

Geez, how sad is your life if you have to steal *rags*? One certainly doesn’t want to be poor. No servants to spring you, for one thing.

Interesting post! I got here via @felonymayhem, btw.

Hi Terry – Yes, the descriptions of the men tell a story, don’t they. I was surprised as how many had smallpox scars, something you don’t see very much on historical dramas. The rich, including royal family, were inoculated. Rags… even they had a value. Naomi