In my previous two posts, I looked at women who sewed and embroidered for a living or because it was part of their domestic duties or as a genteel pastime. Here I explore female artists who used stitchery to create art. Needlework used in this way brings up the whole art versus craft debate. Generally, men were inclined to see art made by men as art and art made by women, especially if they used unconventional media, as craft. But what choice did they have? Women were largely excluded from the male art world, with their lack of presence blamed on their innate lack of genius.

The alternative media – wax, shells, pottery, china painting and shell work – used by women showed their superb creativity. Often these artists were also imaginative businesswomen who undertook the promotion of their work and made a good living for themselves.

MARY DELANY (1700–1788)

Portrait of Mary Delany as an old woman, after J. Opie (1861). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Mary Delany “wrote and illustrated a novel, designed furniture, painted, spun wool, made shellwork, featherwork, silhouettes, invented the entirely new art of paper collage, and was an embroiderer of great artistry, designing her own compositions and relishing painterly effects in embroidery silks.”1 Numerous examples of her work are in the British Museum. She was also a superb plantswoman and botanist.

Although best known for her botanical découpage, which she called ‘paper-mosaics’, she also produced intricate silk-embroidered flower designs such as the satin panel from a mantua (below). The garden historian Mark Laird has said that her embroidery showed “the most accurate horticultural detailing of any work I’ve seen from this period.” It is likely that paid professional embroiderers carried out the highly specialist work (the flowers have a 3D quality not easy for an amateur to achieve), working to her designs.

Delany, née Granville, was born in 1700 at Coulsdon in Wiltshire into a well-connected but not wealthy aristocratic family. At 17 she was married off to 60-year-old Alexander Pendarves, who died seven years later, after which she was free to pursue her interests, despite not inheriting his estate. She was friends with many of the intellectual elite, including Georg Frederick Handel and Hester Thrale, and was acquainted with Robert Hooke, Joseph Banks, Jonathan Swift and Daniel Solander. In 1743 she married a widowed Irish clergyman Dr Patrick Delany with whom she shared an interest in botany and gardening. After being widowed a second time, George III and Queen Charlotte gave her a small house at Windsor and a £300 annual pension. Delany taught the royal children botany and sewing.

Detail from the front panel of the petticoat c.1740. The Gardens Trust has a good post on Mrs Delany’s Petticoat. The dress was of satin with silk embroidery.

Mrs Delany also used a black background for her papercuts, onto which she stuck – using eggwhite or flour and water – tiny pieces of paper building up each part and sometimes using as many as 200 paper petals per flower. To create shading and depth she layered smaller pieces over larger ones, and sometimes added watercolours.

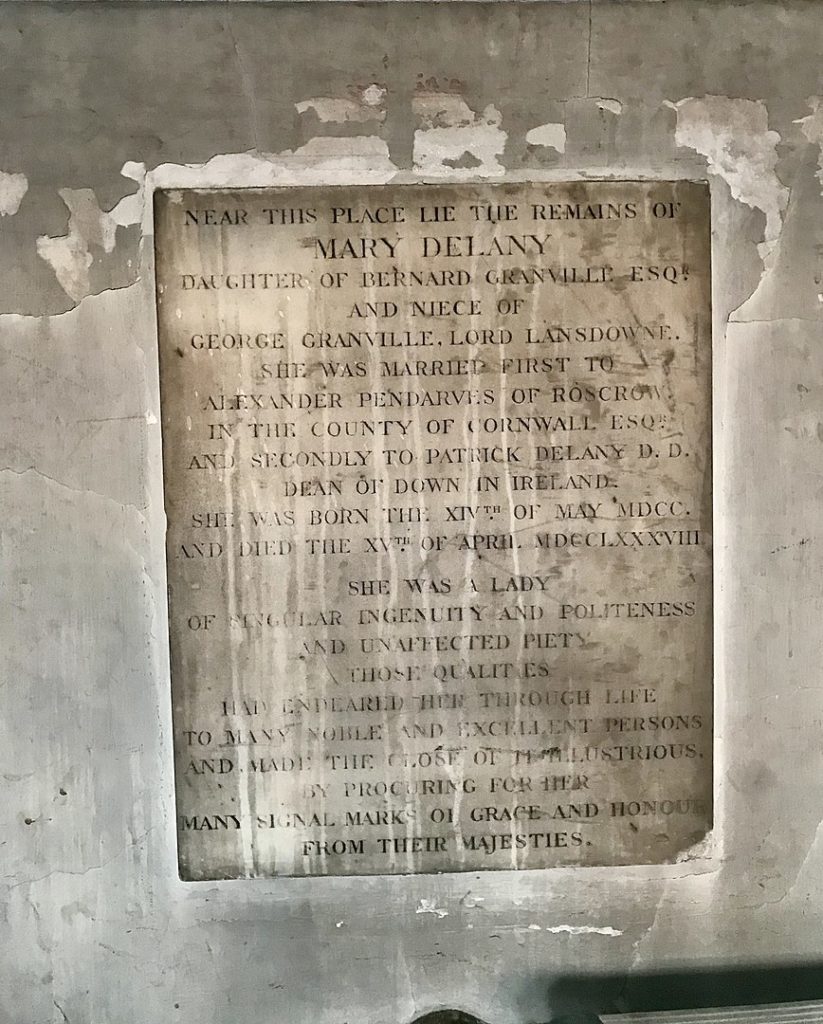

Mary Delany is remembered at St James’s Church, Piccadilly.2

A memorial to Mary Delaney in St James’s Church, Piccadilly. By Tedster007 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

MARY LINWOOD (1755–1845)

On Miss Linwood’s Exhibition.

A FRIEND who witness’d Linwood’s art,

Said, ‘Painting is quite ousted.’

I cried out, ‘no,’ with all my heart,

But own’d it might be worsted.3

John Hoppner, Mary Linwood (c. 1800). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Mary Linwood produced about a hundred works of what was called ‘worsted embroidery’, rendering in unique and intricate sloping stitches versions of old master paintings, a technique known as needle-painting. She was highly celebrated in her long life (she died at the age of 90), met numerous heads of state and her art was exhibited across the Western world. Her works were on display at the Linwood Gallery in Savile House, Leicester Square from 1800 to 1844.

Mary Linwood’s Exhibition in Leicester Square. From Chambers Book of Days, Vol 1.

Mary Linwood was born in Birmingham in 1755, the daughter of a wine merchant; when she was nine her father became bankrupt and the family moved to Leicester, where her mother opened a private school for girls. At the age of 13 she began making embroidered pictures and by 20 was established as a needlework artist (she also had a long parallel career as the head of the girls’ boarding school she inherited from her mother).

In 1786 Linwood was awarded a silver medal by the Society of Artists “for submitting to the inspection of the Society, as examples of works of art, and of useful and elegant employment, three pieces of needlework, representing a hare, still life, and a head of King Lear.”4 After this she came to the attention of Queen Charlotte. The upper-class set, who viewed her works in a private exhibition at the Pantheon in Oxford Street, were highly enthusiastic. She also attracted the attention of the Empress Catherine of Russia and, later, Napoleon gave her a Freedom of Paris award.

Mary Linwood’s 1825 portrait of Napoleon was displayed in the Leicester Square Gallery as number 52, in the ‘Gothic Room’. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

In 1798 she opened an exhibition at the Hanover Square Concert Rooms, which toured Scotland and Ireland; two years later it moved permanently to Leicester Square. Here her works were displayed to best advantage, in large rooms hung with scarlet cloth trimmed with gold. Some were shown in dramatic settings: ‘Lady Jane Grey Visited by the Abbot and Keeper of the Tower at Night’ was viewed down a long passage, as if going to a prison cell, and Thomas Gainsborough’s ‘Cottage Children With an Ass’ was hung as if in a cottage, with visitors peeping through the window.5

Linwood steadily added to the collection. She did all the work herself, from the initial sketches to the embroidery and she personally supervised the dyeing of the fine crewel wool she used. Eventually 64 ‘paintings’ were shown, as well as a self-portrait she did when she was 19. Until she lost her sight in her mid-seventies, she produced over 300 works.

Hanging Partridge, after Moses Haughton. By Mary Linwood (1755-1845) – Bonhams.

In 1838, ill and financially ruined, she offered a hundred works to the British Museum, which rejected them. They raised only £300 at auction. The exhibition closed in 1844, at a time when Linwood’s oeuvre seems to have fallen sharply out of favour. An offer of 3,000 guineas (£3,150) had at one time been refused for ‘Salvatore Mundi’ after Carlo Dolci (Linwood bequeathed it to Queen Victoria) but after her death the remaining collection raised less than £1,000. She died, much loved for her generosity to the poor, the following year.

- Amanda Vickery, ‘A Stitch in Time’, The Guardian, 17 October 2009.

- The British Museum has published a useful factsheet on Mrs Delany.

- Robert Bisset, The historical, biographical, literary, and scientific magazine, The history of Europe, for the year 1799. With an obituary and biographical sketches of persons deceased in that year, &c, vol. 3, Miscellaneous literature, for the year 1799 (London, 1800), 203. Cited in How a lost painting endured: Gainsborough’s Woodman, Macklin’s Poets’ Gallery, and Miss Linwood’s needle painting.. (n.d.) >The Free Library. (2014). Retrieved Aug 23 2019 from https://www.thefreelibrary.com/How+a+lost+painting+endured%3a+Gainsborough%27s+Woodman%2c+Macklin%27s+Poets%27…-a0367076932

- Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists Before 1800.

- The catalogue for the exhibition is available on Google Books.