‘The Double Dealers, Two Strings to Your Bow, or, Who’s the Dupe’, a satire on the broken engagement between Maria Foote and Joseph Hayne. Published by S.W. Fores, 1825. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A tale of broken promises, scandal and lies. The whole sorry story points up the way women living outside respectability were passed, literally like chattels, from the ‘protection’ of one man to another. Even Maria’s own father appears to pimped her out.

In about 1816, actress Maria Foote, then aged about 17 or 18, was invited to perform at Cheltenham Theatre. She had already played Juliet and Miranda as well as many other roles, at her father’s theatre in Plymouth and in Paris, but she was popular with audiences for her beauty rather than her talent.

Maria Foote, by Charles Picart, after George Clint, 1822. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

During the season, the manager of the theatre told her that she had attracted the interest of Colonel William Fitzhardinge Berkeley, the eldest son of the Earl of Berkeley, who wanted to take part in her ‘benefit’.1 Before long, Berkeley and Foote had become lovers, with Berkeley promising marriage. There were obstacles to this: first and foremost, he was a notorious rake and liar; second, he was in the process of laying claim to his inheritance by trying to prove that his parents’ marriage was legitimate.

By this time, Maria was appearing regularly at the Covent Garden Theatre and living with her family at Keppel Street. According to the barrister John Singleton Copley in 1824: ‘The connection was no secret, but it was carried on with so much of decency and decorum, that Miss Foote never passed a night out of her father’s house in Keppel Street during the whole five years that she was under the protection of Colonel Berkeley, nor did the Colonel, in all that time, ever pass a night in that house.’ Despite this, they managed to find opportunities to conceive two children, the first born in 1821 and the second in 1823. On each occasion, Berkeley convinced Maria that she must conceal the births by retreating to the country for her confinement. If she failed to comply ‘he could never … make her his wife’. Within three months of each delivery, she returned to Covent Garden to resume her career. The children remained with wet-nurses and foster families.

After this, Maria decided that this situation could not continue and insisted that Berkeley should marry her, but he continued to fob her off and eventually, she had to accept that he was lying. Luckily, in early 1823, while pregnant with her second child, she made the acquaintance of a young man about town called Joseph Hayne, who had seen her on stage and been overcome with passion for her.2

In order further his suit, Hayne invited Maria’s father Samuel Foote to his ancestral seat at Kitson Hall in Staffordshire, where Foote told him explicitly that for many years his daughter had been engaged to Colonel Berkeley, but if and when this relationship was finally broken off, he was in with a chance. Mr Foote did not mention that his daughter was pregnant with another of Berkeley’s children.

In early June Maria went to Barnard Castle in Durham, 250 miles from London, to give birth to the baby (her father told Hayne she had a ‘pulmonary complaint’ brought on by the smell of gas in theatres) and on her return, Hayne made a firm offer of marriage, Maria having finally given Berkeley the push. Berkeley, who had spies in the Foote household, took it upon himself to tell Hayne about the children, adding that Maria should now choose between the two men. When Hayne said he would break off his relationship with Maria, Berkeley leeringly said he would go immediately and ‘console’ Maria. Berkeley thought the whole thing highly amusing and was said to have given Hayne the nickname ‘Pea Green’.

Joseph ‘Pea Green’ Hayne. © Trustees of the British Museum

Maria wrote to Hayne telling him that she released him from his obligations towards her but wished to explain the situation to him in person; they met up in Marlborough. However, rather than ending it, they renewed their relationship. By now, Maria had the children living with her, but Berkeley was laying claim to them. Hayne was happy to let them go and they were subsequently handed over. Hayne again asked Maria to marry him. By 31 July, she had a firm proposal of marriage in writing.

Meanwhile, a marriage contract was drawn up, in which £40,000 would be settled on Maria, but now Hayne started prevaricating. His friends were not happy about his plans and on the morning of 6 September, the date set for the wedding, his solicitor arrived at Keppel Street with a message that ‘Mr Hayne would never see Miss Foote again.’ The next day, Hayne told Maria that to prevent the marriage someone had plied him with liquor and locked him in a room, from which he had only just managed to escape, and that the marriage would proceed the next day at 9am.

Everything was ready but Hayne never made his appearance. A servant was sent to Hayne at Long’s Hotel and, after a long delay, was informed that Hayne had ‘gone into the country’. After hearing nothing for six days, Maria wrote to her erstwhile fiancé and received a letter in reply in which Hayne claimed he was ‘divided’ between his friends and herself and had resolved to give up his friends. Later, he called on her in Keppel Street and they reconciled. They fixed another day for their marriage: 28 September.

This time, Mr Foote went with Hayne to Doctor’s Commons to obtain a marriage licence, which Hayne himself gave to Maria, saying that he would wait on her the next day. However, it was not Hayne who called but a Mr Manning, who had a message for Maria’s father – to the effect that the engagement was finally and irrevocably broken off. Again, Maria wrote to her suitor, and again Hayne replied that his love was unabated. He asked for another interview, which she agreed to as long as it was in the presence of her family, to which he replied that her last letter to him was couched in terms of ‘inveterate hatred’ and the marriage was off.

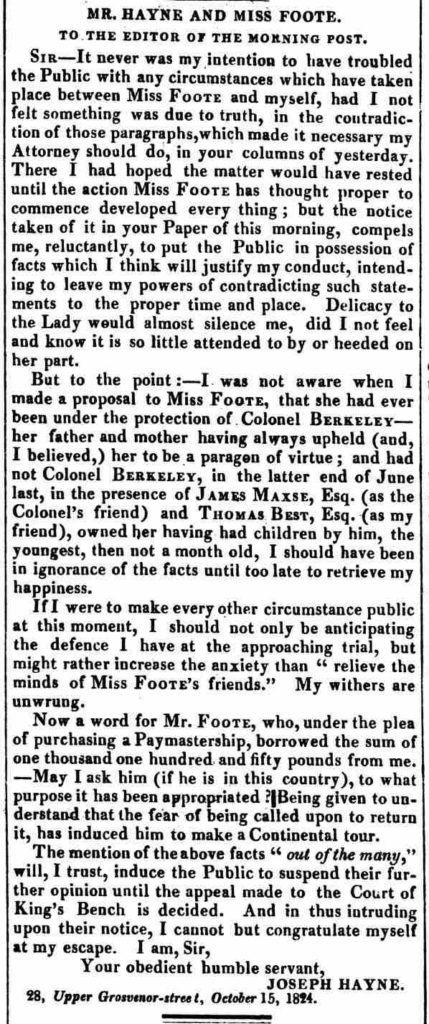

In this, Hayne (or more likely his friends) was anticipating a suit for breach of promise and he was trying to push the responsibility for ending the engagement onto Maria. He had letters published in newspapers asserting that he had not known of Maria’s previous liaison with Berkeley, nor of the children, even though he had renewed his offer of marriage after he was fully apprised of their existence.

Morning Post, 16 October 1824 © British Library

As is often the case, when love wanes, the bitterness turns on money. Maria Foote had called a halt to her professional career, sold her theatrical wardrobe and ordered a carriage. She had lost the chance of a financial settlement from the marriage. She decided to sue for breach of promise to marry, and her case was heard in the Court of King’s Bench in December 1824, where Hayne was represented by the silver-tongued James Scarlet, who made it clear that Maria was little different to a prostitute practised in the arts of seduction, referring to her ‘witchery’ and ‘fascinations’. The jury retired for 15 minutes and came back with a verdict in Maria’s favour and awarded her damages of £3,000, considerably less than her suit but still a sop to her hurt feelings.

Maria’s stage career resumed. When she returned to the Covent Garden Theatre in February 1825, her reception was rapturous. Someone placed a placard with ‘Miss Foote for ever’ on it in front of one of the boxes3. She continued to tour until 1831 when, at the age of about 34 or 35, she married 51-year-old Charles Stanhope, 4th Earl of Harrington, otherwise known as Viscount Petersham, a man of fashion who loved to design his own clothes (he gave his name to the Petersham overcoat and the Harrington hat). They went on to have two children.

Lord Harrington Leaving Mother Matthew’s, by Thomas Rowlandson, undated. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

In 1827 Joseph Hayne, born in Jamaica, married Frances Jane Carter in Millbrook, Hampshire. Maria died in 1867, having outlived her husband by 16 years and the notorious William Fitzhardinge Berkeley by 10.

I hadn’t known that Petersham married, much less that he married a notorious woman. I am not surprised by the actions of Colonel Berkeley. He was just following the actions of his father even though he knew the trouble that could cause the children. He kept his younger brother from assuming the earldom of Berkeley . He was created a peer by William IV in 1831 who made his won bastard one. He hadn’t married by 1842.

Wonder what happened to Maria’s children.

Good question, Nancy. If I find out, I’ll post here. Or if anyone else knows…