Surviving sexual assault was sometimes described as a ‘fate worse than death’ as it inevitably provoked questions about whether the victim had complied with the perpetrator in some way. Indeed, the only good victim was a dead victim and even then, as the death of Mary Ashford showed, it was never impossible to denigrate her. The story of Lavinia Robinson in 1814 is not one of murder but it pointed up the position of women whose reputation was impugned. Facing social humiliation, the possibility that she would forever be seen as ‘damaged goods’, not to mention the loss of her relationship with her fiancé, she was overwhelmed with despair and saw no way forward.

Ophelia by John Everett Millais, painted in 1851-2 © The Tate

The body of 20-year-old Lavinia Robinson was found in the River Irwell on 7 February 1814, over seven weeks after she went missing from her home in Manchester. Had she done away with herself or, as some suspected, was she pushed into the water? And what was the nature of the furious argument she had with her fiancé on the night before she disappeared?

After her parents’ premature deaths, only a few years before her own, Lavinia Robinson and her five sisters supported themselves and their three teenage brothers by converting their home into a seminary. Their resourcefulness enabled them to “keep within the circle of the acquaintance they enjoyed during their father’s life, and to protect the younger branches of the family.”1

Lavinia was described as “a young lady possessing superior mental accomplishments, with a person lovely as her mind, and of the most fascinating manners,” whose compositions “in prose and in verse, breathe throughout the purest sentiments of religion and virtue, and prove her to have had a warm and affectionate heart, great vivacity, and an uncommon playfulness of disposition.” A paragon, in other words.

John Holroyd worked as an accoucheur at the Lying In Hospital (seen on the left). From Lancashire Illustrated by Thomas Allen.

But perhaps not to her fiancé. On the night Lavinia abruptly left her sister’s house in Bridge Street, she and John Holroyd, who was an accoucheur (man-midwife) at Manchester’s Lying-In Hospital, had argued bitterly at the Robinson family home. One of Lavinia’s brothers overheard part of their quarrel.

Holroyd: All’s ready. All’s prepared.

Lavinia: No, don’t. It’s shameful, you shan’t.

Lavinia’s sister Esther, having a cold, had gone to bed early but at 2am was startled awake as if by a loud noise. She could find nothing amiss and went back to sleep but at 3.45 got up to prepare for the chimney sweeps who were coming early in the morning. She noticed that the front door was unlocked. A short time later she discovered that Lavinia was not in the house.

A note was found:

“With my last dying breath, I attest myself innocent of the crime laid to my charge. God bless you all, I cannot outlive his suspicion.”

A few hours after Lavinia was missed, Esther sent for Holroyd, who lived almost opposite the Robinsons’ house, and asked him if he knew where Lavinia was.

“Good God, is she not here?” he replied. He told Esther that he and Lavinia had had a “very serious quarrel” the previous night and that he had left the house just before 12. Later that day, Lavinia’s brother-in-law James Bentley, a cotton manufacturer married to her sister Frances, called on him.

Bentley: Well, Mr Holroyd, what is this business of Lavinia?

Holroyd: Indeed, Sir, I can’t tell. I am miserable. I can’t tell what to do.

Bentley: Esther mentioned a quarrel you had. I should be glad to know the particulars, and what you fell out about.

Holroyd: Why, Mr Bentley, all delicacy in this business must now be laid aside. I discovered—”.

The exact details of Holroyd’s accusations were not published in the newspaper accounts, but later, at the inquest on Lavinia’s death he submitted a written account, in which he stated that he had accused Lavinia of “a want of chastity.”

“I ventured upon the desperate alternative of being convinced of her virtue before marriage. On Thursday evening, Dec 16th., I discovered with horror that my fears were realised. I immediately taxed her with it, in answer to which, she asserted her innocence with considerable vehemence.”

Bentley said that just now he was more interested in Lavinia’s whereabouts than in Holroyd’s suspicions but Holroyd had nothing more to say, except to remark, rather unnecessarily, that “If I marry her, I shall never live long and be always miserable and unhappy” but he did agree to go to the canal with Bentley to look for her. They had no success.

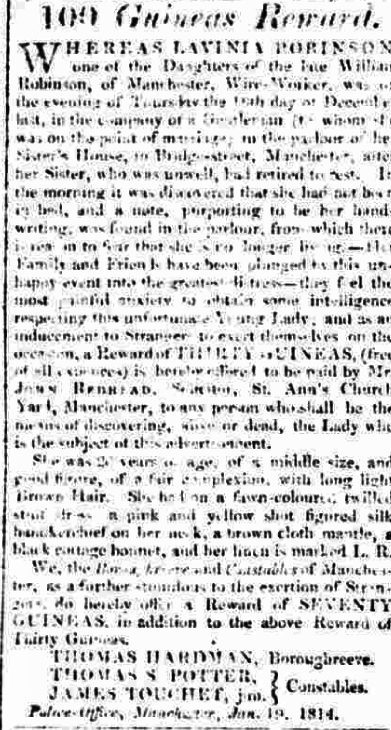

Lavinia’s family reported her missing at the police office and advertised a reward of 30 guineas for her return “live or dead.” During their agonising wait, in the middle of a particularly cold winter, the River Irwell froze over. Their hopes may have been raised when a young woman arrived in distress at the home of a magistrate in Thatcham.2 He suspected that she might be Lavinia Robinson and, when questioned, she said she was – but it turned out that she was lying.

The Robinsons’ advertisement of a reward for the discovery of Lavinia Manchester Mercury, Tuesday 1 February 1814.

Finally, at the beginning of February, the ice on the Irwell began to break up and on 7th Mr Goodier, a millworker, came across Lavinia’s body on a sandbank at Barton. She was still in the fawn-coloured gown she was wearing on the night she left her home, a pink and yellow silk handkerchief around her neck. She had lost a shoe, her mantle and a black beaver hat.

The next day a two-day inquest opened at the Star Inn, under the Coroner Nathaniel Milne. One of Lavinia’s brothers described hearing snatches of the argument between the lovers, her sister Esther spoke of being woken suddenly in the night, and James Bentley detailed his dealings with Holroyd after Lavinia disappeared. Perhaps the most sensational evidence, given what happened to Holroyd afterwards, was from Mr Barlow, who swore he saw a couple matching the description of Holroyd and Lavinia arguing near the western wall of the New Bailey, a stone’s throw from Bridge Street, and that the man struck the woman to the ground. Barlow heard the woman say, “Believe me – but you won’t. I don’t care if you murder me, if you’ll only believe me,” to which the man replied, “Who was it? If you don’t tell me, I’ll never forgive you.”

Mr Ainsworth, the surgeon who performed the autopsy on Lavinia’s body, said her right temple had a crack of two inches, possibly the result of crushing in the ice, and that there was bruising around the neck. Furthermore, there was “nothing to shake their conviction that she had passed a strictly unimpeachable and virtuous course of life.” That is, she was a virgin, and Holroyd’s suspicions were groundless.

Holroyd’s reputation was in tatters, not helped by the fact that two of Lavinia’s sisters and one of her brothers said on oath that they did not believe that the suicide note was in her handwriting. A friend of Holroyd’s said he did not think it was his either, but the damage was done.

Holroyd, who declined to give evidence in person but submitted a written statement, left the court before the verdict was returned.

“That she said Lavinia Robinson was FOUND DROWNED in the river Irwell… but how or by what means she came into the water of the said river no evidence thereof appears to the said jurors.”

That is, an open verdict. There was not enough evidence for a murder charge, nor for the certainty that Lavinia had committed suicide.

After Lavinia’s body was returned to her home, local feeling against Holroyd intensified. Crowds gathered around his residence and grafitti was scrawled on the door and walls. Stones were thrown at the windows. “A kind of fury seemed to hang on the minds of the lower classes of society, which threatened most serious consequences to Mr. Holroyd,” reported Bell’s Weekly Messenger. His employers, the trustees of the Lying-In Hospital, were also disgusted at his behaviour, and sacked him. Fearful for his safety, Holroyd was forced to seek protection at the police office and later, on their advice, left town.

Lavinia’s funeral, attended by hundreds and at which her siblings were said to have been “overwhelmed” with grief, took place on Tuesday 8 February at St John’s Church, Manchester.3 Books of subscription were opened at various places around the city to raise money to defray the expenses of the search and reward. The reward itself became a matter of contention. The Manchester Mercury expressed surprise that “something that occurred when scores of people were employed to break up the ice and which caused him [Goodier, who had found Lavinia’s body] no personal expense could feel that he deserves it.” Goodier gave the 30 guineas back to Lavinia’s sisters, but kept the 70 put up by the city authorities.

In the following month there were rumours that Holroyd had committed suicide at Stafford, but this was a case of mistaken identity, and he was later said to be working as surgeon in his native village of Middlestown near Thornhill in Yorkshire.

The inscription on her gravestone included the following lines:

More lasting than in lines of art

Thy spotless character’s imprest;

Thy worth engraved on every heart,

Thy loss bewail’d in every breast.4

In time, Lavinia became mythologised as the Manchester Ophelia.

- Sources for this story are Manchester Mercury, 15 February 1814; Leeds Mercury, 19 February 1814; Bury and Norwich Post, 2 March 1814; London Courier and Evening Gazette, 19 February 1814; Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 27 February 1814; Saunders’s News-Letter, 7 March 1814; Lancaster Gazette, 23 April 1814.

- It is unclear from the report in the Kentish Weekly Post, 8 February 1814, whether this is Thatcham Green, Staffordshire, 40 miles from Manchester, or Thatcham, Berkshire (170 miles).

- Lavinia’s parents, William (a wire-worker) and Frances, were Dissenters, members of the the Mosley Street Independent Chapel in Manchester. Perhaps Lavinia moved across to the Church of England at the suggestion of her fiancé. Bentley was also an Anglican.

- Quoted in Procter, R. W. (1880). Memorials of Bygone Manchester with Glimpses of the Environs. Manchester: Palmer and Howe.

Leave a Reply