The 18th century was the age of conduct books, manuals dishing out advice, encouragement and a good number of platitudes to people bringing up female children (there were many more conduct books for girls than for boys).

The 18th century was the age of conduct books, manuals dishing out advice, encouragement and a good number of platitudes to people bringing up female children (there were many more conduct books for girls than for boys).

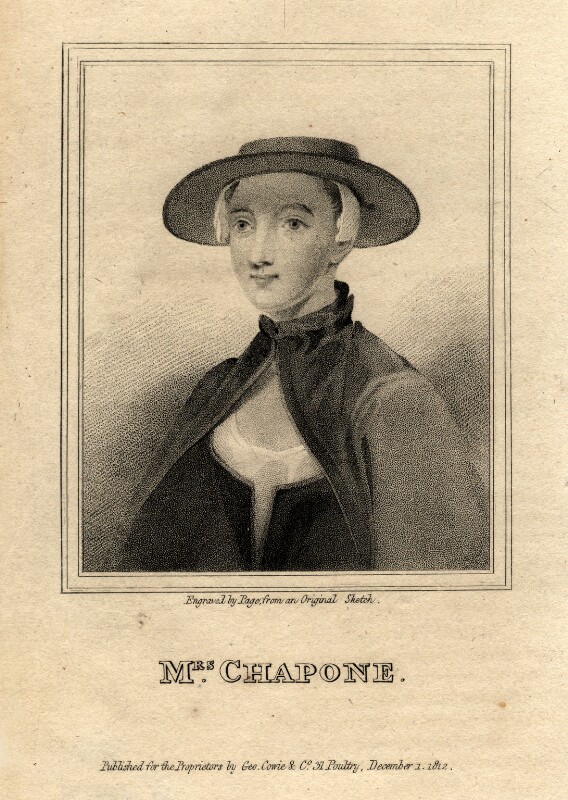

Hester Chapone (1727-1801) by R. Page, 1812 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Hester Chapone’s Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, written in 1773 for her fifteen-year-old niece, advocated a regime for girls based on reading the Bible and the study of history and literature (book-keeping, household management, botany, geology and astronomy were also useful).

Her approach was approved by the radical political philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft whose Thoughts on the Education of Daughters of 1787 promoted self-control and submission (because they enhanced marriage prospects) but simultaneously supported rational independence, religious Dissent and political participation.

Hannah More, by Henry William Pickersgill (1821). Via National Portrait Gallery

Educationist Hannah More1 was politically and socially conservative. While she unquestioningly accepted the position of women as intellectually inferior she aimed to encourage women of the upper classes to act as productive, educated, and morally responsible citizens. In her Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education she suggested that the “chief end to be proposed in cultivating the understandings of women, is to qualify them for the practical purposes of life” (that is, marriage and motherhood). More recommended that a girl should “read the best books, not so much to enable her to talk of them, as to bring the improvement she derives from them to the rectification of her principles, and the formation of her habits.” Women who lack a solid education bring the sex into ridicule. A proper education, on the other hand, brings practical benefits — better run households, for instance (“A sound economy is a sound understanding brought into action”) — and it puts an end to women’s petty struggles for power and equality. “The more her judgment is rectified, the more accurate views will she take of the station she was born to fill and the more readily will she accommodate herself to it.”

Erasmus Darwin, by Joseph Wright of Derby – Unknown, Public Domain, Link

Erasmus Darwin’s2 Plan for the Conduct of Female Education in Boarding Schools, published in 1798, attempted to institutionalise the curriculum proposed by the many conduct books available. Darwin, who opened a school for four pupils, including two daughters of his own, suggested that females should “possess the mild and retiring virtues rather than the bold and dazzling ones” but at the same time stressed that girls should be brought up with enquiring minds and active bodies. His suggested curriculum was wide-ranging: modern languages, geography, history, natural history, embroidery, aesthetics, drawing, mythology, “polite literature” (including carefully selected pieces from the Spectator, Tatler, Guardian), arts and sciences, grammar and arithmetic. Girls should not write for long periods as it keeps the body in a “fix’d posture” (as does drawing and needlework). He recommended instruction in the correct posture and the use of an “inclined desk” (he gave its exact dimensions). His work had specific chapters on compassion and veracity (“the disgrace of telling a lie should be painted in vivid colours” – the boy who cried wolf was recommended) and advice on exercise, dress and “care of the shape” (posture). Although girls were not “brave” in the way boys were expected to be, their “serene strength of mind, which faces unavoidable danger with open eyes, [and is] prepared to counteract or to bear the necessary evils of life, is equally valuable,” he wrote. Extreme timidity was a weakness but so were violent expressions of fear. He advocated confidence but not boastfulness.3

With so much of the advice given in conduct books directed at keeping the young person in check, at regulating her habits, at exhorting her to follow Christian principles and at providing instruction on how she ought to be behaving it is difficult to avoid the suspicion that Georgian teenage girls were no different to those of any other era, that is that their decision-making powers were sometimes deformed by the action of a tsunami of hormones on their brains; that some of them were easy to live with, docile and sweet-natured; and that some of them were rebellious, irrational, confrontational, devious and strong-willed.

Not dissimilar to boys, really.

- Hannah More, Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education With a View of the Principles and Conduct Prevalent Among Women of Rank and Fortune. T. Cadell and W. Davies, London, 1799.

- Erasmus Dawin, Plan for the Conduct of Female Education in Boarding Schools. J. Johnson, London, 1797. Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), the grandfather of Charles Darwin, was a physician, natural philosopher, physiologist and slave trade abolitionist. His most important scientific work was Zoonomia, in which he anticipated the theory of natural selection.

- Christopher Upham Murray Smith, The Genius of Erasmus Darwin. Ashgate Publishing, 2005

Years ago, I read an antique novel (I believe it was a series), about a young single father and his little daughter. 19th-20th century. She strives to please his unreachable expectations of perfection and he is brutally harsh and emotionally abusive to her. Although the book did not paint him as an antagonist in that time period. At one point, she hardly messes up and he gives her the silent treatment for an extremely unbelievable amount of time and she becomes I’ll and almost dies, over her grief. Can you help me find the title of this book? Thank you