Prompted by an interesting piece in History Today about the fear of criminal “monsters” and moral panic in the 18th and 19th centuries, I thought I would take a closer look at the word monster, as it was applied, albeit obliquely, to the person at the centre of my book The Disappearance of Maria Glenn.

Latterly, the word has been used as an adjective (monster trucks), drawing on its connotations of “huge” and “overwhelming”.

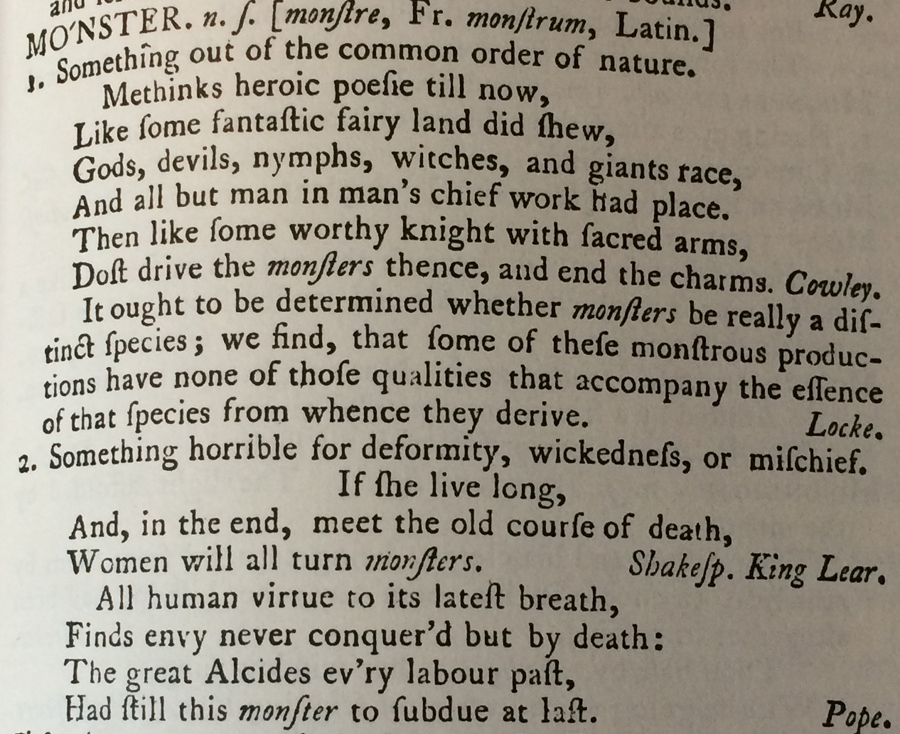

This is how Samuel Johnson defined it.

- Something out of the common order of nature.

- Something horrible for deformity, wickedness, or mischief.

He cited a servant in King Lear:

If she live long,

And, in the end, meet the old course of death,

Women will all turn monsters.

Johnson noted that monster was also a verb but that it was “not in use.” It is now back with us, with the meaning to criticise or reprimand, literally, to make a monster of.

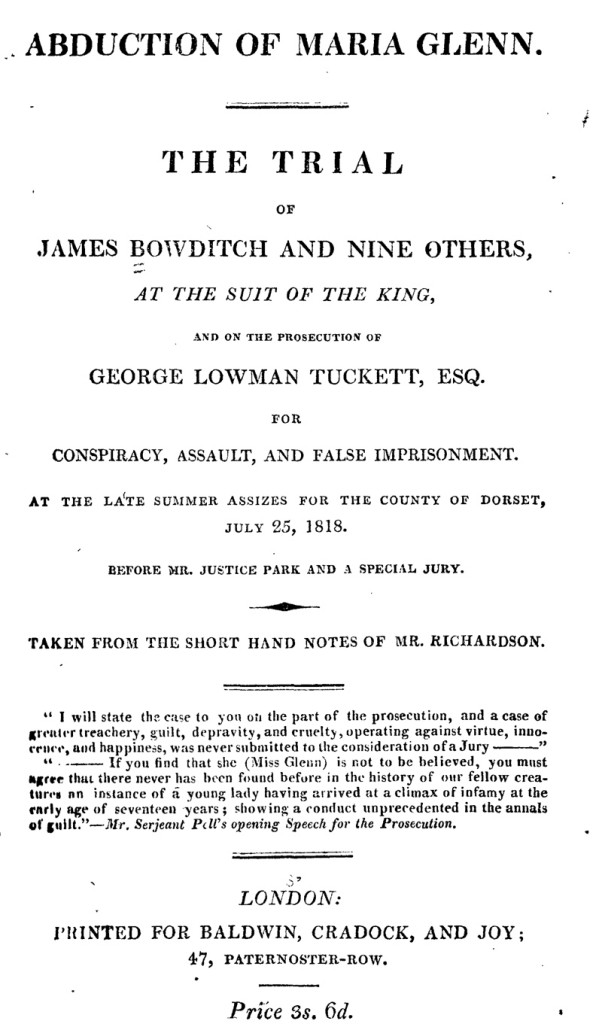

The word monster was used by prosecution barrister Albert Pell at the 1818 Summer Assizes held in the Shire Hall at Dorchester, during the trial of the Bowditch family (and others). Maria Glenn, the star prosecution witness, alleged that the family had forcibly abducted her in order to marry her to the youngest son. She was then 16.

The very foundation of the case rests upon the character of this young lady for truth. If you do not believe her, and if she fails to obtain your credit, you must of necessity believe her to be a perfect monster of human treachery.”

But what did Pell mean? And why did he use that particular word, which raised the possibility that Miss Glenn was indeed a liar, a “monster of human treachery.” Ah, he went on, never before has there been an instance of a young lady having arrived at such a “climax of infamy at the early age of seventeen, showing conduct totally unprecedented in the annals of guilt.” This was Pell’s rather backhanded way of saying that Maria was too young and innocent to make up stories in the way that infamous female liars had done in the past.

The Georgians set the bar for respectable girls’ behaviour very high. They were required to suppress any natural exuberance or rebelliousness. Independent thinking was not encouraged, although education was useful so that they would be competent to run households, converse with their husbands and bring up children, especially boys. They were to be, at all times, submissive to their husbands and others in authority, chaste, sensible, honest, pure, loyal and, above all, truthful, and anything that deviated from this was aberrant – it made them “monstrous”. Parents perplexed at how to instil these ideal habits in wayward daughters could consult the plentiful advice available, in the form of conduct books. The reality of family life, of course, was that people, female or male, were their imperfect selves; girls talked back, rolled down hills for fun (I am thinking of the young Jane Austen), asserted themselves when pressurised into matrimonial self-sacrifice (Elizabeth Bennet is a fictitious example) and ran off to marry their true loves (Julia Maria Petre and Stephen Phillips, one example of thousands), or even insisted on having careers (Mary Wollstonecraft and her erstwhile charge Margaret Mason, who became a doctor).1

Most girls, however, did not have options. They were in an invidious position (“What has changed?” I hear you ask). They were encouraged to strive for perfection in behaviour and attitude (they could only fail), but this was only done through fighting their core natures. It was accepted that females were natural liars (they were, after all, descendants of Eve, the first to fall), deficient in intelligence and at the mercy of their biology. Menstruation not only enfeebled them physically and mentally but also caused them to become rapacious as their bodies tried to fulfil their natural function: to become pregnant and bear children. If they were not held in check they would revert to their true natures: lascivious, wanton and untrustworthy.

At its most extreme, men’s theories about women included the idea that females were so inept, stupid and ignorant that they could be regarded for practical purposes as simple-minded. In Lord Chesterfield’s famous and widely published – and approved of – advice to his son:

Women, then, are only children of a larger growth; they have an entertaining tattle, and sometimes wit; but for solid reasoning, good sense, I never knew in my life one that had it, or who reasoned or acted consequentially for four-and-twenty hours together. Some little passion or humour always breaks upon their best resolutions. Their beauty neglected or controverted, their age increased, or their supposed understandings depreciated, instantly kindles their little passions, and overturns any system of consequential conduct, that in their most reasonable moments they might have been capable of forming.’ 2

Females should be treated with caution; those telling extraordinary stories must be disbelieved. Disaster followed if they were not. Over half a century before Maria appeared as a witness in Dorchester, public opinion – seemingly across whole country – had been split about the truth of a tale told by a young woman who claimed to have escaped after having been abducted.

On the evening of New Year’s Day 1753, 47 years before Maria was born, Canning, a stocky, pock-marked 17-year-old, disappeared after visiting relatives in East Smithfield in London. Her uncle and aunt had accompanied her part of the way home, leaving her to walk the remaining half a mile across Moorfields, a large and notoriously risky open area, to her place in Aldermanbury Postern where she worked as a live-in scullery maid to Edward Lion, a prosperous carpenter. That was the last anyone saw of her until she returned to her despairing parents a month later. She arrived in a “deplorable condition,” a bloody rag around her head, her face and hands black with dirt and with a wound to her ear. Her story, whose details changed constantly, was that she had been kidnapped by “two lusty men” during her journey across Moorfields. They shouted “Damn you, you bitch, we’ll do for you by and by,” and held her up under the arms, which induced her to have a fit. Almost the next thing she knew was that she was in the hayloft of a house. There, during the entire 28 days of her imprisonment, she lived on only a few scraps of bread and a pitcher of water. Her captors put her under pressure to become a prostitute (she refused) and her stays were cut off and stolen.

After her extraordinary capture and incarceration, Elizabeth made an equally amazing escape. At about four in the afternoon on 29 January she simply “pulled down a board that was nailed to the window, and getting her head first out, she kept fast hold by the wall, and then dropped into a narrow place by a lane, behind which was a field.” She asked strangers the way to London and was back at Moorfields by ten and home not long afterwards.

Almost at random a mob, led by Edward Lion and John Wintlebury, identified Enfield Wash in Hertfordshire as the place of her torment and Susannah Wells and Mary Squires, the two elderly women living there, as her jailers. The women were hauled off to a local magistrate and committed. The theft of Canning’s stays, valued at over 10 shillings, was a hanging offence.

Their trial at a packed Old Bailey three months later was chaotic. A hostile crowd had gathered outside and witnesses for the defence were deliberately intimidated. Nevertheless, three men, John Gibbon, William Clark and Thomas Greville, who had made the effort to travel from their homes in Abbotsbury in Dorset (only 10 miles from Dorchester) to provide an alibi for Squires, made it through. Unfortunately, desperate to avoid the gallows, Squires offered a second alibi story, and this had the effect of undermining the evidence of the Dorset men, who were later charged with perjury.

Canning also benefited from the influence of Henry Fielding, the novelist and magistrate, who had earlier assisted personally at the interview of Virtue Hall, a prostitute who was in the house when Wells and Squires were apprehended. Hall initially gave testimony in support of the women but Fielding persuaded her to change her mind and her testimony formed the main plank of evidence against her former friends.

Wells was duly sentenced to branding on the thumb and imprisonment and Squires to hanging. At this point, Sir Crisp Gasgoyne, the most senior of the judges at the trial, expressed serious concerns about the anomalies in Canning’s tale and the naked prejudice against the women, who were or were thought to be Gypsies. He launched an independent inquiry and sought out new witnesses. He interviewed Virtue Hall, who promptly changed her story again, this time in support of the women. By now, everyone had a theory about the case and London opinion became split between Canningites and ‘Egyptians.’

By mid-1753 it was clear to most that Wells and Squires were innocent and Canning had been lying. Gascoyne persuaded the King to pardon Squires but Wells had already suffered her punishment. In September, the three Dorset men were acquitted of perjury and, in the following April, Canning found herself arraigned for “wilful and corrupt perjury.” She was found guilty and sentenced to a month’s imprisonment and seven years transportation to America.

Canning died in America in 1773, having married the great-nephew of the Governor of Connecticut and produced five children. There was no deathbed confession and her whereabouts in January 1753 remain a mystery. It has been suggested that she absented herself in order to give birth or to undergo an abortion, or that she was pursuing an illicit affair or was pushed temporarily into prostitution. No one can know. What we can be sure of is that she lied comprehensively about the days she was missing. The only rational explanation was that telling the truth was too appalling to contemplate and that once in the care of her concerned friends and their vigilante hangers-on she supplied answers to their many questions with little thought as to the consequences.

Newspapers devoted yards of columns to the Canning case and the trials produced a storm of pamphlets arguing forcefully pro and anti. The constant retelling of the story in popular publications such as The Newgate Calendar, a collection of lurid tales about the perpetrators of murder, treason, rape and other heinous offences that was published and republished in many different editions until 1840, ensured that Canning’s name remained in the public consciousness for decades afterwards. It would certainly have been well known to everyone in the Shire Hall in 1818 for the Bowditch trial.

3

There was another, and much more recent, case to reinforce public uneasiness about young females with a sensational tale to tell and it would have been uppermost in the minds of the jury in 1818. In April the previous year, the nation was transfixed by the story of Princess Caraboo, a mysterious young woman who had turned up in a distressed condition in the village of Almondsbury in Gloucestershire and was taken in by the local magistrate and his wife. She had persuaded her kindly and somewhat gullible hosts into believing she was a lost princess from “Javasu.” In reality she was Mary Willcocks, the daughter of a poor cobbler from Witheridge in Devon. Her dark colouring, the strange language she spoke and the clothes she was wearing – a black gown and turban – gave her authenticity, which was bolstered when a Portuguese traveller claimed that he could understand her. He was able to relate her amazing story, a convoluted tale of abduction by pirates, a long and arduous sea journey and a daring escape during which she jumped overboard in the Bristol Channel and swam to the shore.

Caraboo delighted her hosts with her eccentric behaviour: she fenced beautifully, was a good shot with a home-made bow and arrow, swam naked in the lake and prayed to “Allah Tallah.” Newspapers up and down the country reported her story and gentlefolk from all over came to peer at and wonder over her. Caraboo agreed to inscribe examples of her language which were duly sent for identification to Oxford, where the scholars immediately denounced them as “humbug.”

Caraboo was recognised by a Bristol lodging-house keeper who had read her description in the Bristol Journal. In June 1817 she was quietly hustled off to America in the care of three strictly religious ladies. A narrative of her life, complete with details of her disturbed and restless wanderings (she had spent some time in Taunton) before she fetched up in Gloucestershire, was published soon afterwards.

4

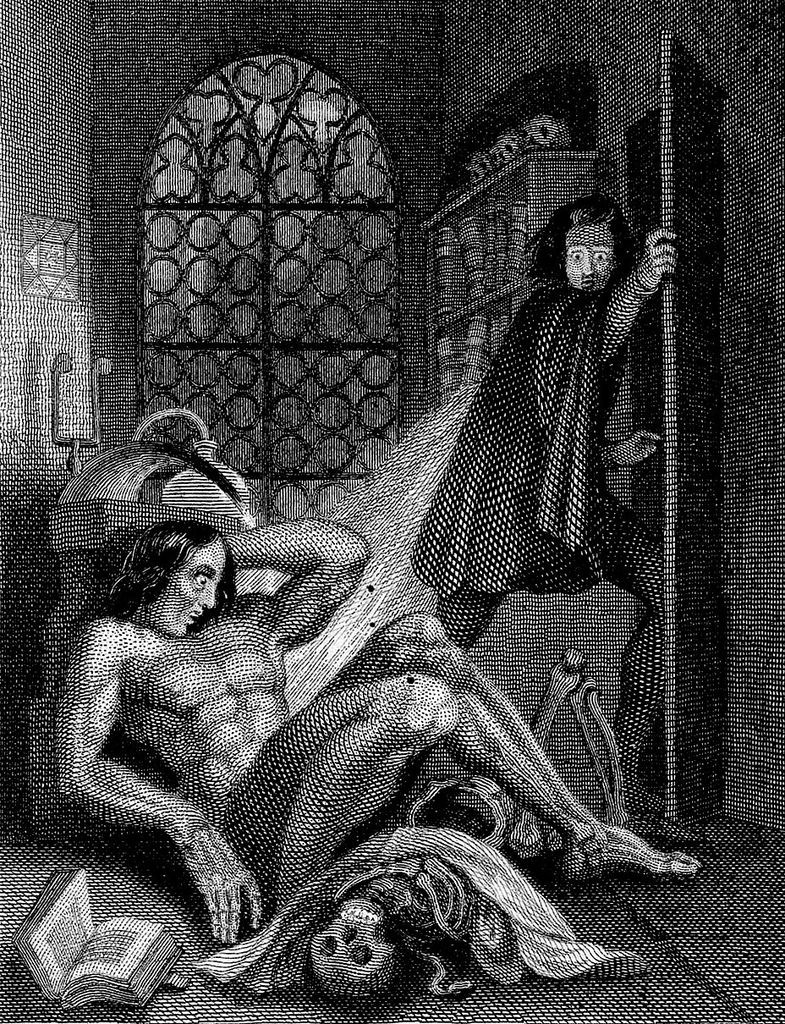

In March 1818, five months before the Dorchester trial, a new monster, albeit not a female one, was unleashed into the public imagination. Five hundred copies of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus, were printed and despite almost universally bad reviews—The Quarterly Review savaged it but La Belle Assemblée was kinder (“This is a very bold fiction; and, did not the author, in a short Preface, make a kind of apology, we should almost pronounce it to be impious”)—made an instant impression on the reading public.

The novel was panned for its crudeness and lack of religious sensibility, and for those reviewers who knew that the anonymous author was a woman, gender was certainly an issue:

5The writer of it is, we understand, a female; this is an aggravation of that which is the prevailing fault of the novel; but if our authoress can forget the gentleness of her sex, it is no reason why we should; and we shall therefore dismiss the novel without further comment.” British Critic

Shelley herself was a monster; she had transgressed social rules by running away with a married man and now she had rejected or abandoned the aspirations that should have been natural to one of her sex and produced a work full of “horror which …is too grotesque and bizarre ever to approach near the sublime” and which arose from her “diseased and wandering imagination, which has stepped out of all legitimate bounds”.

6She was indeed “Something horrible for deformity, wickedness, or mischief.”

It is impossible to say whether Albert Pell had read the novel or the reviews of it, and whether he made use of the word monster knowing that it would resonate with the Special jury. As a Special Jury, they were hand-picked from the gentleman class, and the foreman was Henry Bankes, the Tory local MP and owner of Corfe Castle and Kingston Lacy.

Certainly, by using the word, Pell would have hoped to show that Maria was not a monster but a truthful and respectable female – but he may have presented her opponents with a gift. A useful phrase, packed with fear and loathing, with which to monster her.

- Six foot tall Margaret, the daughter of Irish aristocrats, wore male clothes in order to pass for a man and study medicine.

- Letter CLXI, London, 5 September 1748. Letters Written by the Late Right Honourable Philip Dormer Stanhope. J. Nichols et al, London, 1800

- John Treherne’s The Canning Enigma (Jonathan Cape, London 1989) is recommended reading, as is the chapter on Canning in The Secret History of Georgian London by Dan Cruickshank (Random House, London 2010).

- Caraboo: A Narrative of a Singular Imposition. London, 1817.

- The British Critic, N.S., 9 (April 1818), p.432-38.

- Charlotte Gordon’s Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley (Hutchinson, 2015) is highly recommended reading.

Leave a Reply