Following on from last month’s blog on breastfeeding, I have compiled a short visual tour of the lives of very young Georgians by way of sketches, paintings and cartoons. The depictions offer sharp contrasts in the fates of babies. All babies are vulnerable, in generations past much more so than now, but some were more vulnerable than others. No prizes for guessing what determined their life chances. All of these depictions are by men. Just saying. Genuinely, no more than that.

Let’s start at the top end of the social scale with this 1799 scene by William Redmore Bigg entitled Birth of the Heir showing the presentation of a newborn baby boy to his father and sisters. The older woman is probably the children’s grandmother. Here is not the place to debate the relative social positions of female and male children in genteel families but it’s probably enough to say that the father looks both misty-eyed and relieved (he’s been up half the night, as evidenced by his brandy, soup and sandwiches, and he has a son at last). For me there is an air of concern about the scene, leaving me to wonder whether all is well with the mother. The maid about to leave the room looks caringly on the new baby’s sisters and the grandmother seems a mite serious.

William Redmore Bigg, 1755–1828, Birth of the Heir, ca. 1799, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

This portrait of the West family, by Benjamin West, is much more formal. Betsy West, who has just given birth to her second child, wears a shimmering white gown matching the robes her baby wears, and gazes calmly on her child. The father of the child, Benjamin West, wearing lilac robes to balance his son’s outfit on the left, looks on from the right, while his father John and brother Thomas, both Quakers, sit in stolid homage. The painting was described by the Morning Chronicle as a ‘neat little scene of domestic happiness’1 but for me it’s curiously unfamilial: unnaturally silent and still, staged like a medieval nativity.

Benjamin West, 1738–1820, The Artist and His Family, ca. 1772, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

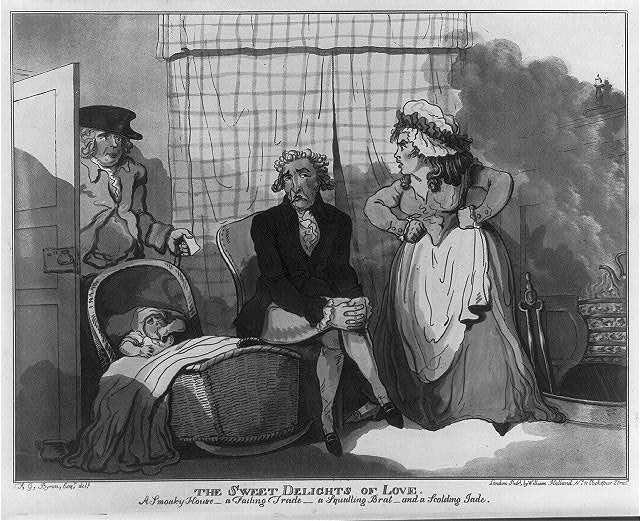

There is no celebration of birth in Frederick George Byron satirical scene, entitled The Sweet Delights of Love and published at some time between 1788 and 1792. The baby here is decidedly unattractive, the mother is a termagant and the father’s trade is failing. Everything is going up in smoke.

F.G. Byron, The sweet delights of love. Courtesy of Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003675436/

This next couple are much happier. In Thomas Rowlandson’s Four O’Clock in the Country a chubby child sleeps soundly and contentedly as his excessively déshabillée mother helps his father get ready to leave on a pre-dawn hunt. The baby’s relaxed pose and rounded limbs are of a piece with its parents’ obvious pleasure in the delights of conjugal love.

Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827), Four O’Clock in the Country, (c 1788-90), Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

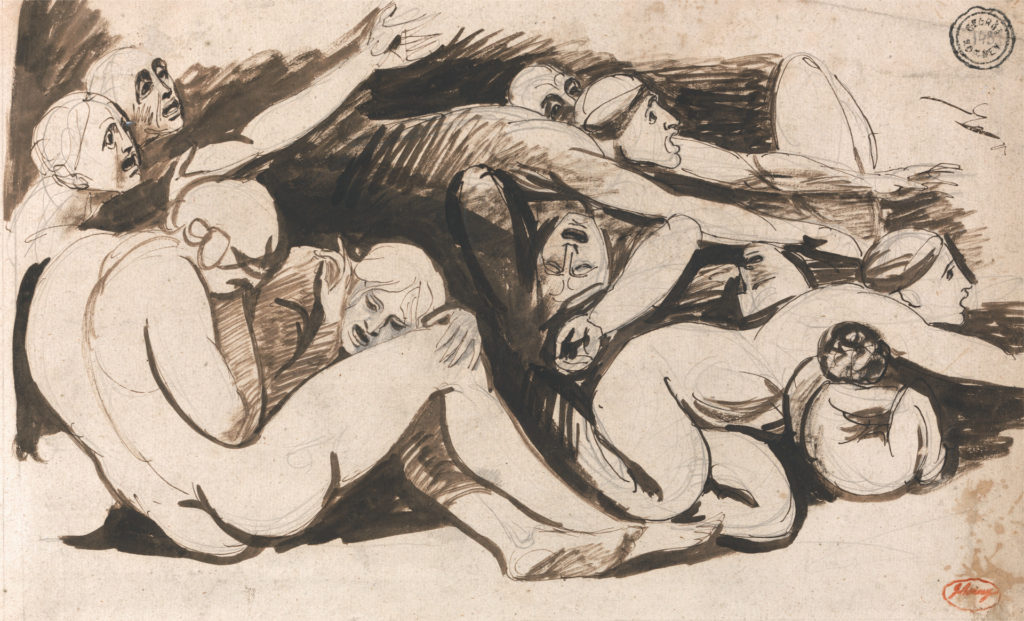

Moving down to the bottom of the social scale now, here is George Romney’s sketch of a prison scene, which is like something out of Hell, which indeed was Romney’s point. Unnoticed in the mêlée is a child curled up in the uncertain protection of its mother’s armpit. Extremely stylised, almost 20th-century in its reduction of the human objects to geometric shapes, it vividly conveys the pain and degradation of incarceration. A baby who can be only be utterly innocent of any crime is not exempt from punishment for its parents’ crimes. 2

George Romney, 1734–1802, British, Prison Scene, undated, Brown wash and graphite with pen and brown ink on medium, moderately textured, cream laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Yale Art Gallery Collection, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. Richardson Dilworth, B.A. 1938

To finish, I give you Joseph Highmore’s Angel of Mercy, currently on display at The Foundling Museum in London as part of their Basic Instincts exhibition.3 The painting, in which a desperate mother is averted from strangling her newborn child is averted from committing murder by an angel, is probably a study for a larger work intended for the Foundling Hospital but never created. According to Jacqueline Riding, who curated the exhibition of Joseph Highmore’s work, the subject matter was probably too shocking for contemporary audiences.

Joseph Highmore (1692–1780), The Angel of Mercy, ca. 1746. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The punishment of women who kill their babies is one of the subjects I cover in my new book Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches, which will be published next month and is available for pre-order here.

The punishment of women who kill their babies is one of the subjects I cover in my new book Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches, which will be published next month and is available for pre-order here.

WOW! How absolutely fascinating! Thank you so much.