When a woman could not or would not breastfeed, the most obvious solution was to find a surrogate or wet nurse, a woman who had either recently given birth, who could supply enough milk for two babies or who was still in milk after weaning her own child.

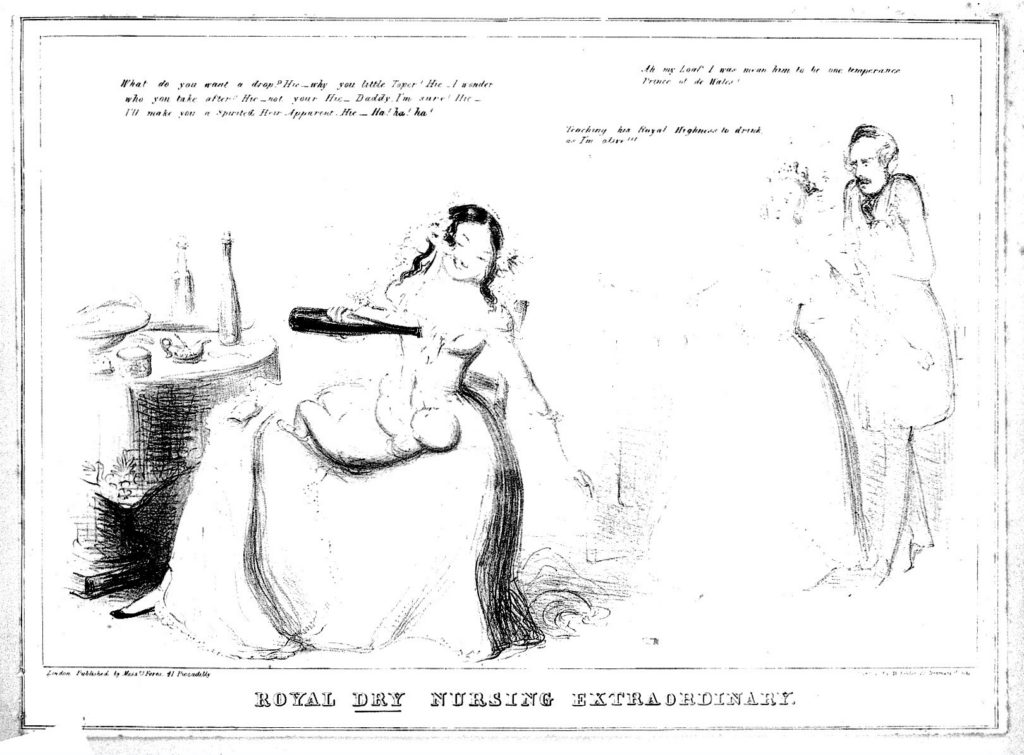

It was standard practice to hand royal or high-born babies straight to a nurse, who often had special status within the household. In 1766, after careful vetting, Mrs Muttlebury, a mother of four, was employed by Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, to feed her first daughter, Princess Charlotte. Mrs Muttlebury’s reward was substantial: £200 per annum for life. Apart from the salary, she would also have benefited from the contraceptive effect of prolonged suckling. Queen Charlotte, on the other hand, had to return to the task of producing more royal progeny as quickly as possible. She had 15. Queen Victoria, who bore nine without much enthusiasm for pregnancy or indeed children, famously did not breastfeed, thinking it a repulsive and animalistic practice suitable only for the lower classes.

Middle-class women who assisted their spouses in their businesses, the wives of wives of merchants, lawyers, and doctors for example, also may not have breastfed because it was less expensive to employ a wet nurse than to hire someone to run their husband’s affairs in their stead. However, there was a growing feeling towards the end of the 18th century, partly driven by the involvement of doctors, invariably men, in pregnancy, birth and babies, areas of life traditionally dominated by women, that it was preferable for children to be fed by their natural mother.

Hugh Smith, Physician to the Middlesex Hospital, wrote that ‘nothing but a strange perversion of human nature could first deprive children of their mother’s milk… milk is a natural support which the great Author of our being has provided for our infant state.’ He bemoaned the feeling against women suckling their own babies. He warned that failure to breastfeed could produce tumours and other cancers. He was not keen on wet nursing and warned against the dangers of allowing ‘a strange woman’ to suckle a child, fearing that diseases – the king’s evil, watery gripes, rickets – could be imbibed at the breast and that a wet nurse might be tempted to abandon or farm out her own child in order to take wet nursing employment.1

In general wet nurses did not have a good reputation and were distrusted by people like Dr Smith for their ignorance and their tendency to administer dangerous opiates such as Godfrey’s Cordial (nicknamed Quietness for obvious reasons).

Of course, no matter the rank of a family, if the mother died around the time of birth, feeding the newborn became an immediate problem. If a wet nurse was not available or not desirable what could you do? Smith felt the best substitute was artificial or hand feeding with cow’s milk, which should be boiled and sweetened with sugar.

Some care-givers supplemented artificial feed with pap, which consisted of bread soaked in water or milk, delivered using a pap boat with a hollow stem which allowed the pap (or pananda which was cereal cooked in broth) to be blown down the child’s throat. Along with linen pouches, horns, clay jugs, pickled cow nipples and other vessels used to feed babies, these objects, difficult to clean and never sterilised, were the frequent source of infection. About a third of infants who were artificially fed died during their first year.

The forces of the Industrial Revolution, pushing rural families to the cities, affected breastfeeding. Casual and reciprocal wet nursing between friends and neighbours had existed for centuries, allowing women to work away from home in the fields. Now urban women, who were more likely to have to work outside the home to supplement their families’ incomes, found that it was difficult, if not impossible, to breastfeed on demand. Babies were often farmed out in the countryside to impoverished women where they would either be wet nursed or fed with cow’s milk or pap. Unsurprisingly they suffered a high rate of mortality.

Stevens, E. E., Patrick, T. E., & Pickler, R. (2009). A History of Infant Feeding. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 18 (2), 32–39. http://doi.org/10.1624/105812409X426314

Wickes, I. G. (1953). A History of Infant Feeding: Part III: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Writers. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 28 (140), 332–340.

Leave a Reply