George Cruikshank, Very Unpleasant Weather, or, the Old Saying Verified “Raining Cats, Dogs, & Pitchforks.”!!! (1835). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Machine-breaking is more usually remembered as the destruction of mechanised looms in the five years between 1811 and 1816 but it also occurred in fields and farms in the early 1830s.

According to the 1841 census 22 per cent of the population (1,138,563 people) worked in agriculture in England and Wales 1, a figure that was judged to be slightly under the true one.2What was life like for them? In short, harsh.

Peter DeWint, British, Threshing Corn, undated. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The population was booming, which meant increased pressure on jobs and society was changing. The enclosure of common land, on which smallholders had once grazed animals or grown subsistence crops, forced many to become hired hands in insecure employment on low wages. Cottage industries, which traditionally provided a living for women and children, were being replaced by factories. It got worse as the century progressed. After 1815, with the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the country entered a major recession. The large numbers of demobbed militia travelling the country and looking for work brought even more pressure on jobs. Wages went down, food prices went up. In 1816 there were pockets of starvation across the country. This was the so-called Year Without a Summer when the harvest was severely impacted by meteorological changes arising from the massive eruption of Mount Tambora.

People did whatever they could to get by: poaching, stealing for which they risked imprisonment or transportation. If they entered the poorhouse they had to contend with social disgrace and humiliation. Following a particularly bad harvest, anger and frustration erupted in Kent on 28 August 1830 when a threshing machine, the hated symbol of change and suffering, was attacked. Around a hundred such attacks occurred in the next few years, mostly in the south-east and Midlands.

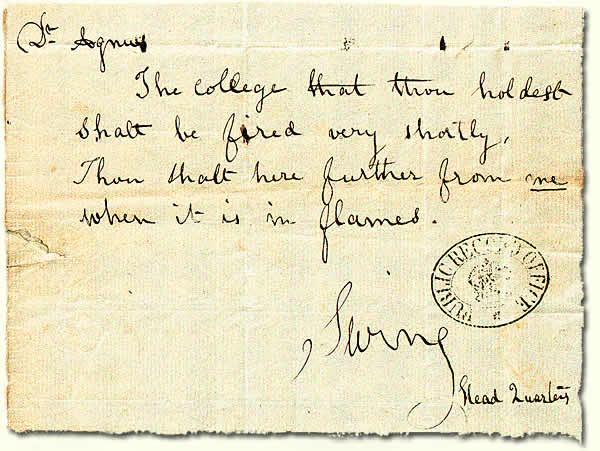

Example of letter sent during the Swing Riots. This letter was sent to Corp. Christ. Coll. Cambridge in 1830. It says: “Dr Agnus. The college that thou holdest shalt be fired very shortly. Thou shalt here further from me when it is in flames. Swing Head Quarters.” Copyright The National Archives Via Wikicommons

These eruptions of anger were dubbed the Swing Riots, the name possibly deriving from the action of hand scything. Typically the protesters sent a letter, purportedly from ‘Captain Swing’, to local bigwigs (clergy, landed farmers, magistrates and Poor Law guardians) threatening violence and demanding better wages, reduced tithes and the dismantling of threshing machines.

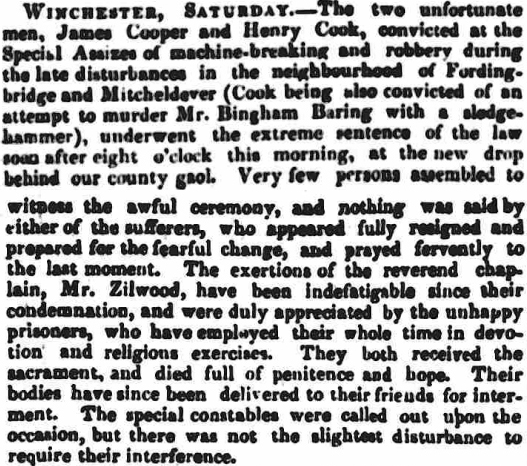

Despite the rallying cry of ‘Bread or Blood’, casualties were few and there was only one death. The focus was buildings, threshing machines and hayricks rather than people. Nearly 2000 protesters were brought to trial and of those 252 were sentenced to death (19 were hanged) and the rest imprisoned or transported.

Bell’s Weekly Messenger – Monday 17 January 1831, 5B. © The British Library Board

The Swing Riots contributed to the push for reform of the electoral system and the Poor Laws in the 1830s. The freethinker William Cobbett, who wrote the polemical Rural Rides, an account of his journeys in southern England, was a supporter of the rioters, for which he was prosecuted for sedition by the Whig government.

That was not the end of rural discontent nor of Swing. In February 1834 George and James Loveless, James Hammett, James Brine, Thomas Standfield and Thomas’s son John were charged with having taken an illegal oath, in effect to have formed a union to protest about their meagre pay, and were transportation to New South Wales. After three years, they were pardoned and returned to England. The trade union movement was born.

- www.visionofbritain.org.uk

- According to the peeved number-crunchers in the census office, the census takers persisted, despite instruction, in erroneously classifying farm servants housed in farm-houses and employed generally about the premises as domestic servants.

Leave a Reply