The death of Ann Baker, who went to the gallows at Mount Pleasant in Oakham, Rutland1 on 3 August 1801, merited few newspaper column inches. Her conviction, alongside John Eaton2 excited little comment, even though it was rare to condemn a woman to death and even rarer to do so for stealing animals.

A Dishley ram and a Dishley ewe. Coloured stipple engraving

Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.

Between 1735 to 1799 in the whole of England only five women were executed for stealing sheep or horses,3 the most recent being Diana Davis4, who, with her son John, was convicted at Presteigne in Radnorshire in 1797. The judge, George Hardinge, who became notorious in 1805 for sending 17-year-old infanticide Mary Morgan to her death and then wept over her grave, pardoned John but hanged Diana.5

Sheep stealing was typically committed by men, usually working in groups of two or three. And although sheep stealing had been a capital offence since 1741, a time of rural hunger and high prices, it was not regarded as a crime on the level of horse stealing. The most usual punishments were imprisonment and transportation rather than death.

In Rutland itself, sheep stealing was evidently not a major problem before the turn of the 19th century: in the years 1735 to 1799 no one, male or female, had hanged for it6 Why, then, were Baker and Eaton seemingly so unlucky?

One reason was that the years 1800 to 1802 were characterised by high food prices. Not surprisingly, there was corresponding increase in hunger, and therefore in sheep theft.7 Sheep were easy prey, temptingly small and more tractable than cattle. They could be taken off and butchered in a field, and they yielded valuable meat, tallow, fat and skin, for sale or for use at home.

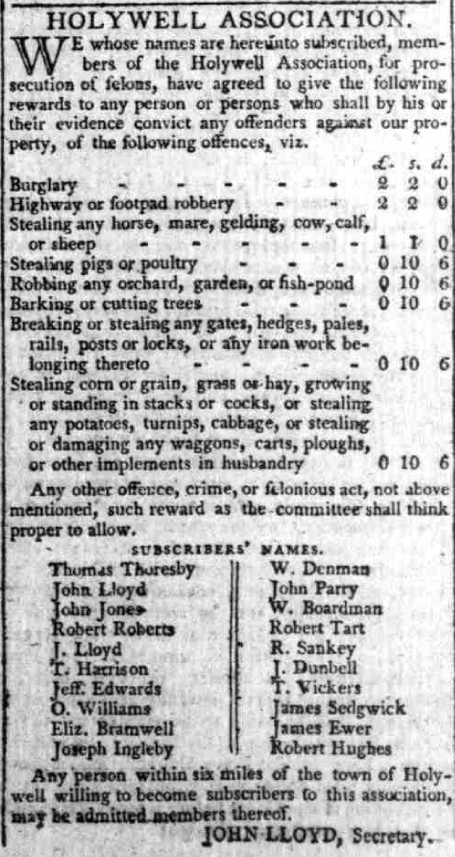

In many areas respectable citizens – farmers, smallholders and householders – unable to bear the cost of prosecuting felons individually banded together to form associations. They offered rewards for evidence leading to conviction, including for sheep stealing. An example was Holywell Association, which advertised its rates in The Chester Chronicle8. One woman, Elizabeth Bramwell, probably a widow, was among the subscribers.

Chester Chronicle, 2 August 1799. © The British Library Board

Holywell was offering £1 1 shilling for evidence concerning sheep stealing. By 1801, however, the problem had become so extensive that rates had risen substantially. The Staffordshire Advertiser reported:

Sheep-stealing, and other crimes, have of late become so prevalent, that the associations for prosecuting felons in different parts of the country are advertising increased rewards for the detection of offenders. Church Eaton association has advanced the reward for the apprehension of sheep-stealers, &c, to fifty pounds.

The Thrapston association in Northamptonshire bought a blood hound specifically to detect sheep thieves. According to The Chester Chronicle, during a test of its effectiveness, the animal chased his quarry for an hour and a half “notwithstanding a very indifferent scent” and found him secreted in a tree 15 miles from the start.9

Near Clipsham, Rutland: View towards Osbonall Wood from the Stretton Road © Copyright Christine Johnstone and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

Without details of Ann Baker’s trial or of her record of offending, it is impossible to know how she was regarded by the court or why she and Eaton were condemned and others imprisoned or transported. The Stamford Mercury reported that they went to their deaths having acknowledged their guilt and “behaved with propriety in their unhappy situations.” Eaton “met his fate rather with an appearance of satisfaction than dismay; but the poor woman was much affected.”10

It is probable that they were repeat offenders, and that they were seen as a scourge of their community. They lived at Clipsham, a village of fewer than 200 people11 so they would have been well known to their neighbours; their victim, Mr Wyles, lived at Stretton, a mile and a half away. Perhaps Wyles or his association, if he belonged to one, pressed for the ultimate sanction or the judge made a random decision to hold them up as examples.

Ann Baker’s execution for sheep stealing was the first in England and Wales in the 19th century. It was also the last time a woman was executed for the crime. But it was not until 1832 that sheep, cattle and horse stealing, along with shoplifting, were removed from the list of felonies for which you could end up at the end of a rope.

- A History of the County of Rutland: Volume 2.

- Sometimes given as Exton.

- Information from the invaluable Capital Punishment website.

- Sometimes given as Davies.

- John Barrell, “The Australian Convicts of Radnorshire” in Radnorshire Society Transactions. Vol. 60 (1990), p 27-35.

- Information from Capital Punishment website.

- J. M. Beattie, Crime and the Courts in England 1660-1800. Princeton University Press, 1986

- 2 August 1799.

- 21 October 1803.

- 7 August 1801. The very next paragraph in the report gives the punishment of “three more sheep stealers”: they were merely committed to Oakham gaol.

- Vision of Britain

Leave a Reply