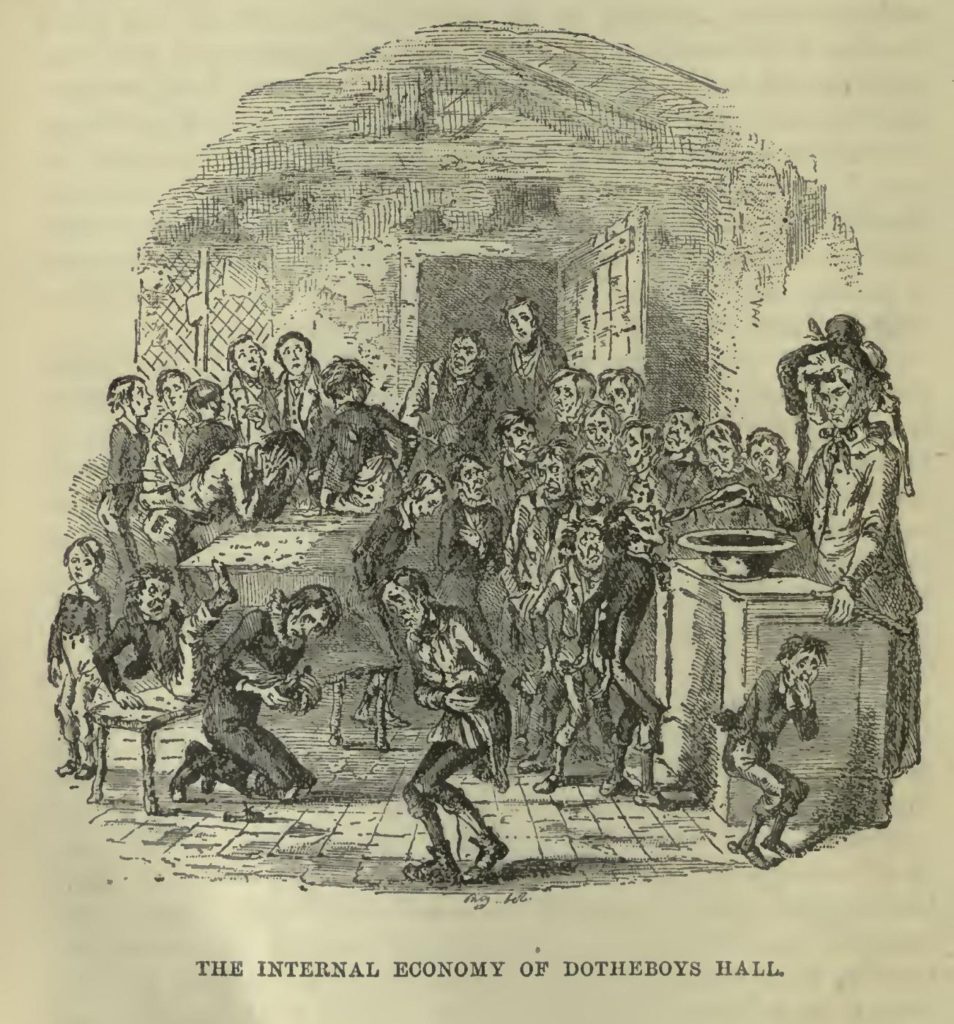

Pale and haggard faces, lank and bony figures, children with the countenances of old men, deformities with irons upon their limbs, boys of stunted growth, and others whose long meagre legs would hardly bear their stooping bodies, all crowded on the view together; there were the bleared eye, the hare-lip, the crooked foot, and every ugliness or distortion that told of unnatural aversion conceived by parents for their offspring, or of young lives which, from the earliest dawn of infancy, had been one horrible endurance of cruelty and neglect.

Charles Dickens describes the Dotheboys pupils, Nicholas Nickleby, 1838-9

The flying visit Charles Dickens and his illustrator Hablot “Phiz” Browne paid in 1838 to Greta Bridge, a newspaper cutting about ‘The Cruelty of a Headmaster’ in his pocket, is well known. Dickens was on a mission to investigate the business of the ‘prison schools’ of Yorkshire and Teesside and wanted to meet William Shaw who had been prosecuted in 1823 for causing some of his pupils to go blind. Shaw was fined the huge sum of £600, but seemed to shrug it off and merely returned home to continue to run his business.

Pretending to be acting for a widow hoping to place her son at the school and looking for guidance, Dickens introduced himself to a local solicitor, Richard Barnes, who outlined the local options.

Later, Barnes appeared at the inn where Dickens was staying, to warn him off.

‘I’m dom’d if ar can gang to bed and not telee, for the weedur’s sak, to keep the lattle boy from our schoolmeasthers,’ he said. Dickens used him as the model for the hero John Browdie in Nicholas Nickleby.

During his trip, Dickens tried to visit Shaw’s academy at Bowes but was refused at the door, Shaw having been forewarned that a writer was nosing around the area. In their brief encounter, however, Dickens noted that Shaw had lost an eye and used this as a characteristic of Wackford Squeers, the hilariously corrupt and ignorant proprietor of Dotheboys Hall. He found another character while at Bowes: while walking in the churchyard he saw, among the many graves of schoolchildren, a headstone for George Ashton Taylor, who had died at Shaw’s Academy in 1822, aged 19. He was the inspiration for Smike.

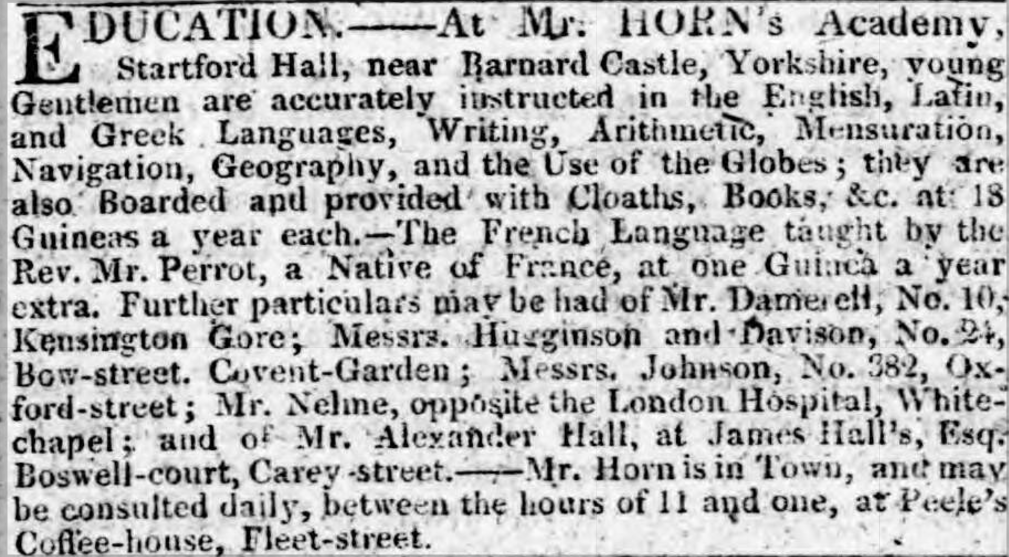

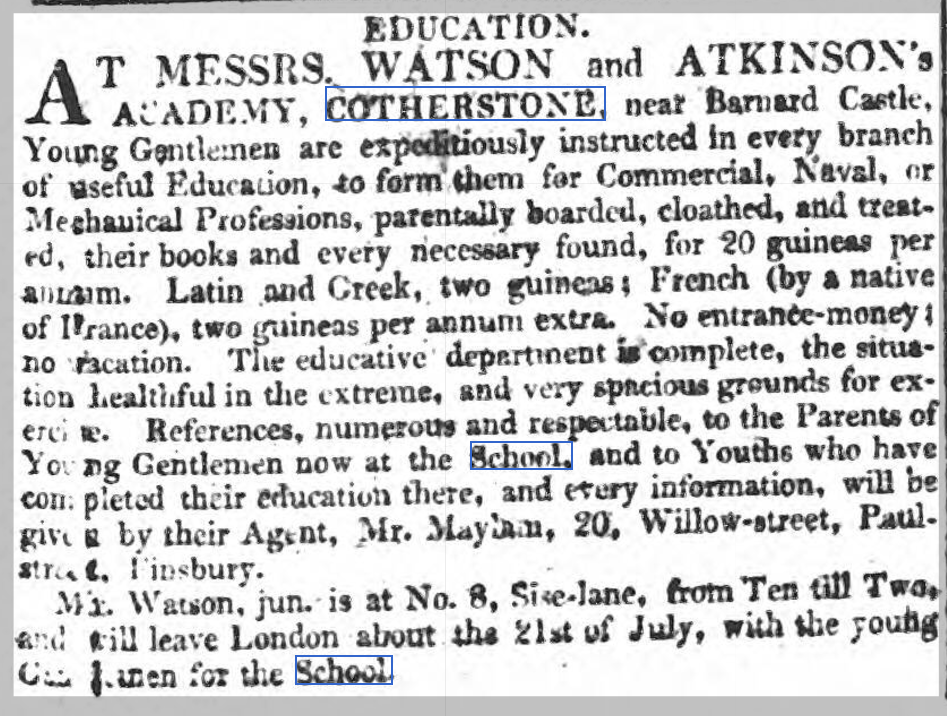

Many well-meaning but impecunious parents (widows on small incomes for instance or widowers suddenly in charge of large numbers of children) placed their children in what were called the Yorkshire Schools. After all, the advertisements promised great things:

Some parents were more keen on the convenience offered by the schools, which were perfect for people whose offspring were in some way inconvenient, usually because of their illegitimacy or disability. The cost was relatively low: each child could be lodged permanently for around £20 a year, often all year round. Dickens included this feature in his fictional ad for Dotheboys Hall which was almost a verbatim copy of one for Bowes Academy printed in The Times in 1817. The school at Cotherstone in the North Riding of Yorkshire run by Joseph Watson and Charles Atkinson, who had bought it from the Reverend Joseph Adamthwaite, also offered this option.

In 1814, Joseph Death, of Shoreditch, the father of ten children, met Mr Watson’s son, also called Joseph, in London and agreed terms for two of his sons, Jeremiah, who was about seven, and Francis, six. They were to bring their own clothes but the school would provide great coats, the cost of which would be charged back to Mr Death. Death no doubt assumed that the boys would thrive in the country air in a spartan but caring environment.

The reality was quite different. The house was freezing cold; its one schoolroom was equipped only with a tiny stove and no chairs. The boys’ clothes were appropriated by the Watsons and they were made to wear thin rags and wooden clogs. The food was cheap and of poor quality. The boys soon became infested with vermin and covered in sores. A local cobbler, Watson’s brother-in-law, taught reading and writing. There was no instruction in Latin or Greek.

A Mr Smith, whose own son Thomas was at the Cotherstone school, learned about the appalling conditions from some former pupils. Alarmed, he went to see Joseph Watson Jr when he was next in London and demanded Thomas’s immediate return. In January, when Thomas failed to appear, he decided to travel to Cotherstone to collect him, first informing other parents of his acquaintance, including Mr Death, who asked him to collect his boys at the same time.

Smith found the boys in a shocking state. They were undernourished, wearing rags and freezing cold. Francis Death’s feet were covered in infected sores. In all, Smith removed seven boys and travelled back to London with them.

Understandably, Mr Death refused to settle his bill with the school. In March 1816 Watson and Atkinson sued him, little thinking that even a successful prosecution might not do them much good in the long run. The case was heard by Lord Ellenborough, the reactionary Lord Chief Justice, prosecuted by Charles Williams and defended by William Garrow, at that time Attorney General.1

In court, the conditions of the school were exposed – and disputed. Joseph Watson Jr claimed that the Death boys were given greatcoats and pocket money and various other witnesses testified to good food and reasonable care, but the French teacher (it’s somewhat surprising that they had one) said ‘he would not expose a dog’ to the treatment the boys had to endure, that ‘there was no more knowledge of geometry and geography in the school than an ass had of astronomy’. There were ‘no books, no fire, and he still felt the effects of the frost’. He was forced to lend Watson and Atkinson money, which was not returned, and had been paid wages in linen and calico rather than cash. Unlike the former owner, neither Watson nor Atkinson were ordained ministers of the church. In fact, it transpired that Mr Watson had previously been a butcher. His 70-year-old wife, whose job it was to care for the boys, spent the days sitting about with another old woman smoking a pipe.

Despite this, and the evidence of Mr Moorhead, a London surgeon, who testified that the Death boys were weak and in bad health from ‘want of nourishment’, the jury found for the plaintiffs, awarding them damages of £17 18s and costs of 40s (£2).

The case hinged on the food. Jeremiah Death said breakfast, dinner and supper were provided and ‘sometimes’ this included meat, broth, vegetables and ‘brown cake’. Thomas Smith, now aged 14, said that he was given porridge for breakfast and dinners of meat and potatoes. Lord Ellenborough said objections to such food ‘arose out of the foolish luxury of the metropolis’ and asked the jury whether this could really be described as ‘starving’. In his opinion, the breakfast sounded very wholesome.

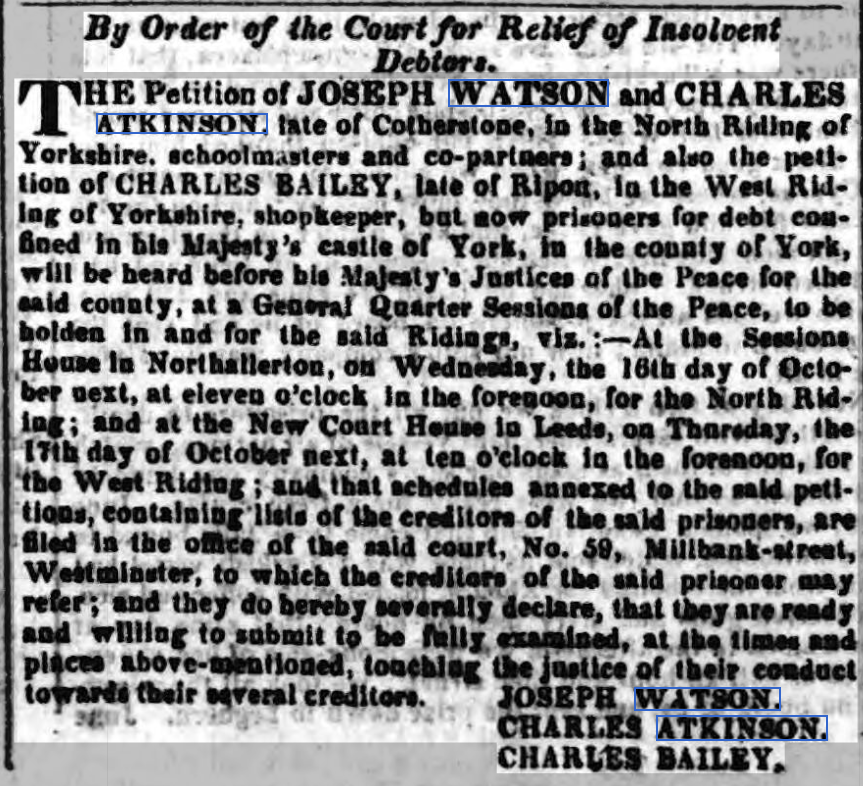

It was a pyrrhic victory for Watson and Atkinson because the case killed off their business. By September of 1816 they were imprisoned in York Castle for debt and petitioning for insolvency relief.

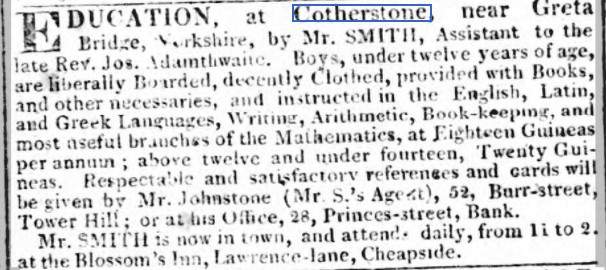

The school itself continued under new management, run by a Mr Smith (no relation to the man who retrieved his son from the school). His ad made no mention of Watson and Atkinson but emphasised his credentials as a protégé of Mr Adamthwaite. The boys were ‘liberally’ boarded.

Shaw’s Academy closed, along with many others, in 1840.

Further reading

John Sutherland, Nicholas Nickleby and the Yorkshire schools (British Library)

[…] far away from his grave at the back of the churchyard is another tombstone – that of George Ashton Taylor, thought to be the inspiration for the character of Smike, the school friend of Nicholas […]