Before the fire of 1834, members of the House of Commons sat in the secularised Royal Chapel of St Stephen, a two-storey building with high turrets at each corner, which had been extensively remodelled by Sir Christopher Wren in 1692. Facilities were notoriously cramped and inconvenient.

Thompson, The Houses of Parliament with the Royal Procession (1804). The Chapel of St Stephen, where the Commons sat, is on the left. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

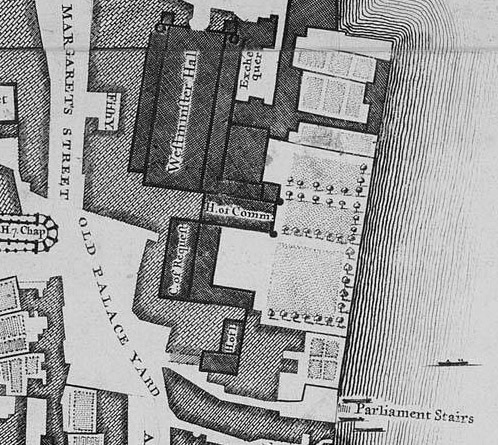

In the early 19th century, as part of a redevelopment programme, James Wyatt moved the Lords into the Court of Requests. John Rocque’s map shows the positions of the Houses of Commons and Lords in 1746.

The Palace of Westminster was a firetrap and MPs and architects, including John Soane, had been predicting disaster since at least the late 18th century. In 1828, Soane warned that ‘the want of security from fire, the narrow, gloomy and unhealthy passages, and the insufficiency of the accommodations in this building are important objections which call loudly for revision and speedy amendment.’ He was ignored.

The catastrophic fire of 16 October 1834 arose, bizarrely, from an archaic way of accounting used by the Court of Exchequer. Until 1826, when the Court was abolished, it had kept records of payments using a system of tallies, elm or willow wood sticks split in half (one half was retained by the Exchequer, the other half acted as a receipt). A decision was made to burn the now redundant sticks, two cartloads full, in furnaces directly under the House of Lords.

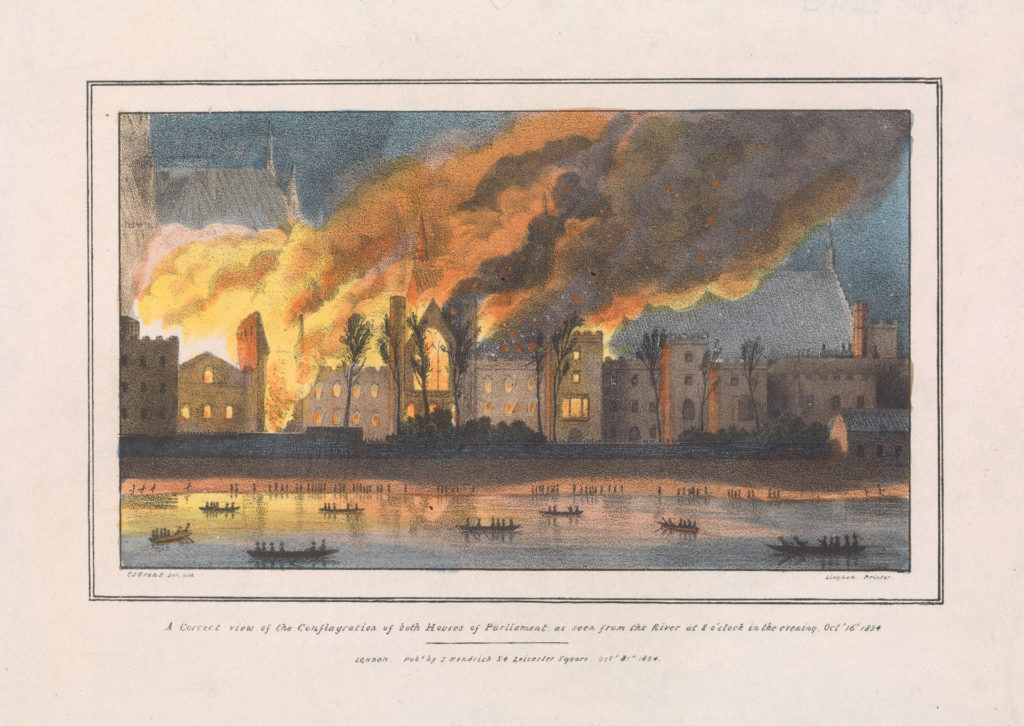

Charles Jameson Grant, A Correct View of the Conflagration of Parliament as Seen from the River at 8 o’clock in the Evening Oct. 16th 1834 (1834). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

The fire was first spotted at around 6 o’clock that evening and half an hour later there was a massive flashover, followed by an explosion. At 7pm James Braidwood,1 who had been appointed the first Superintendent of the London Fire Engine Establishment only 18 months previously, was alerted and arrived at the scene 25 minutes later with 14 or 15 engines and 66 firefighters, just as the roof of the House of Lords crashed in.

James Braidwood, via Wikimedia Commons

The fire, which was the largest in London since 1666, lit up the skyline of London and could be seen by the Royal family at Windsor. It burned all night and the damage was extensive. St Stephen’s Chapel, the Lords, the Painted Chamber and the official residences of the Speaker and the Clerk of the House of Commons were destroyed. Braidwood’s decision to focus efforts on saving as much as possible from the relatively unaffected areas while abandoning the buildings obviously beyond salvation meant that St Mary Undercroft, Westminster Hall, the Cloisters and the Jewel Tower survived.

The 1834 destruction of both Houses of Parliament by fire via Wikimedia Commons.

Recommended reading: Shenton, C., (2012). The Day Parliament Burned Down. Oxford: OUP.

Leave a Reply