The story of the death of Annette (or Ann) Paris in London of an overdose of laudanum in January 1810 has many layers and shows that it is not always wise to accept the first, or indeed any, version of events as reported. Initially, it appeared that the unhappy Annette (or sometimes Ann) Paris had been betrayed in love and, in the depths of depression over her situation as an abandoned wife, took her own life. The truth turned out to be far more complicated.

George Tierney dressed as an executioner by James Gilray, part of the ‘French habits’ series. Courtesy of British Cartoon Prints Collection (Library of Congress)

Annette was born in Paris, the daughter of a Monsieur Paris, who, as the Bristol Mirror stated on 13 January 1810, “was well known in the commencement of the Revolution, and in which he suffered.1 Madame Paris fled to London with Annette and, having lost all means of support, took a job as a governess with a family in Scotland. She later returned to London where she lived in the New Road (now called Euston Road). After her mother died of a stroke, Annette was sent to boarding school in Brunswick Square, her education paid for by Henry Peirse, the MP for Northallerton, who acted as her guardian.

Annette grew into a beautiful young woman who, by the time she was seventeen, was accomplished in singing and playing the piano, spoke French and Italian and had read “beyond her years”. But her early traumatic experiences had sewn the seeds of tragedy.

The first newspaper reports of her death included the following account:

About six or eight months ago she was met in the square, when walking with the other young ladies, by a young man, in the dress of a midshipman, who followed her to the door, and who wrote to her under the name of Jones. A correspondence took place; her imagination was fired; and she eloped with him under promise of marriage. His address was found in her box, and they were traced her guardian and separated. Jones declared that she was virtuous, that his intentions were most honorable; and, as a proof of it, was ready to marry her with her guardian’s consent. In fact they were married, and she was completely undone. In about a fortnight or three weeks Jones threw off his disguise, and fairly told her his real character that he was no sailor, but lived by his shifts; that he had married her only for the sum her protector had paid him, and that she must provide for herself. She was abandoned; and the shock had such an effect upon her imagination, that she has ever since shewed signs of a disordered intellect. —Bristol Mirror, 13 January 1810

An Elopement by Moonlight by Charles B. Newhouse (1834). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

In this state of mind, she took up with a officer who had a reputation as a womaniser. “This fatal attachment absorbed her whole soul, and in the frenzy of this passion, she took the desperate resolution of poisoning herself.” Using some pretext she asked her servant to obtain laudanum, took an overdose and, despite the efforts of two medical gentlemen, expired.

But was this the whole truth of the story? Along with the first version, the Bristol Mirror offered a second version.

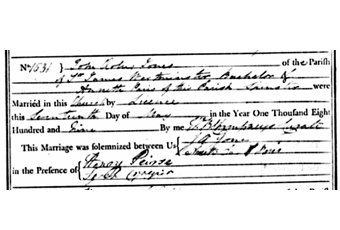

In this alternative version Annette’s husband John Arthur Jones was not a midshipman, nor was he a scoundrel. He was a Lieutenant in the Navy, and the son of a wealthy army clothier, who had met Miss Paris “at the Foundling [Hospital]”2. Was it her vulnerable emotional state that led her to run off in the middle of the night to be with him? It was scandalous behaviour and Jones showed both sense and compassion when he brought her back to her governess. A short time later he proposed marriage. Annette’s guardian Mr Peirse approved of the match and settled £60 annually on the couple. They were married at St Pancras parish church on 17 May 1809.

Soon afterwards, she and John moved in with his parents but after arguments and conflict they took lodgings in Camden Town or Edgeware Road. The marriage did not fare well. After a month, John began to suspect Annette of infidelity. He arranged to have her watched and his suspicions were not only correct but worse than he imagined. Annette was apparently going “upon the town”, that is she was prostituting herself.

Annette moved to 4 St Martin’s Street, Leicester Fields. It is most likely to have been around this point that she became involved with the Captain who betrayed her. More of him later.

Annette’s risky behaviour was a sign that her mental state was deteriorating. Sarah Upton, her maid, told the coroner’s inquest3 that “the unfortunate young lady appeared to be rather flighty and tiresome in her manner, such as ringing the bell violently, giving orders and almost immediately after giving counter orders. She was also extremely incoherent in her discourse, rambling from one subject to another with the utmost rapidity, and without there being the least connection between each.”

On the day she drank the laudanum, Annette went out at two in the afternoon and returned at half past six. She told Sarah that she had given coachman £1 although the fare was only 2 shillings. She left the house again and returned at eight “her bonnet all bedizened with artificial flowers”. Later, after a period of apparent calm, “with the utmost wildness in her countenance, she exclaimed, ‘Oh, I shall never see him [the womanising officer, presumably] again! I have done the job — I have taken good care that the laudanum I took shall do the business.'”

Sarah bolted upstairs to find that the phials of laudanum she had earlier been asked to buy for Annette were now empty. She called in medical help but shortly afterwards Annette sank into stupefaction. She was beyond help and died the next morning.

Sarah bolted upstairs to find that the phials of laudanum she had earlier been asked to buy for Annette were now empty. She called in medical help but shortly afterwards Annette sank into stupefaction. She was beyond help and died the next morning.

The coroner’s jury returned a verdict of Insanity.

The authors of the newspaper reports certainly display compassion for her mental state and, without blaming her personally, regretted that she lacked the anchors of “solid education, mental improvement, of moral and Christian knowledge” (Bristol Mirror). The moralising is confined to a quote from Nathaniel Cotton’s poem ‘Health’4:

He who at his early years

Has sown in Vice, shall reap in Tears.

It is not surprising that Annette chose laudanum, a liquid form of opium mixed with combinations of saffron, castor, ambergris, musk, nutmeg, honey, licorice. It was cheap and widely and freely available from apothecaries and grocer’s shops. It was often given for “hysteria,” the female complaint associated with the possession of a womb. It had almost universal appeal; it was not just the drug of choice of poets and writers (Coleridge, De Quincey, Barrett Browning), royalty and aristocracy (George III, the Prince Regent, Georgiana the Duchess of Devonshire and her mother Lady Spencer) but of the poor and discarded.

There is a postscript to this tale, given by the Bristol Mirror:

We had to record time time ago, the unfortunate death of Miss Paris, who poisoned herself through jealousy. We have now relate an accident almost as tragical, which befel a young female equally unfortunate: —Captain, as well known in the fashionable world, as in the rules of some of our prisons, is the hero of both tragedies. This man, it seems, makes it a practice and a pastime to seduce young females by false promises, and to work their feelings to the highest pitch, by alternatives of romantic love and jealousy. The young woman in question is hardly eighteen years of age. He seduced her about two years ago, and shortly after abandoned her to the wide world. Her infatuation, however, still continued. A year ago she attempted to drown herself on his account; but he still contrived to keep hope alive, which is his constant practice. He left her for Miss Paris, and on the death of that unfortunate young woman, found no difficulty in renewing his connection with her. He had left her on Sunday evening, appointing her to meet him (it being Term time) on Monday, at a small cottage near Baker street, where she found on the table love-letters, left on purpose to inflame her feelings, and directed to two females, equally heedless. She went home, worked up to a phrenzy of despair, and took a quantity of laudanum. She persisted in refusing every kind of remedy, till he himself came to administer it. She is not yet out of danger.

[Updated 15 July 2017]

- According to Louis Marie Prudhomme, Histoire générale et impartiale des erreurs, des fautes et des crimes commis pendant la Révolution française, a dater du 24 août 1787;: contenant le nombre des individus qui ont péri par la révolution, de ceux qui ont émigré, et les intrigues des factions qui pendant ce tems ont désolé la France. Paris: s.n., 1796. (compiled as a database on ancestry.co.uk) there were seven men of the name Paris who were guillotined. The most likely candidate for Annette’s father, in my view, is Pierre Louis Paris, a teacher from Paris.

- Presumably a social or fund-raising event.

- The inquest was held at the Nag’s Head, Orange Court, Leicester Fields, before Anthony Gell, Coroner for Westminster.

- Nathaniel Cotton (1707–1788) was a poet and doctor. These lines are from ‘Health’, which is part of his Visions in Verse series.

Leave a Reply