Warwick Assize court. August 1817. Abraham Thornton is on trial for his life, accused of the murder of Mary Ashford, whose body has been found in a stagnant pond just outside the village of Erdington, near Birmingham. Thornton’s defence is that he was not with her when she died – he was miles away, walking home after parting with Mary during the early hours. Several eyewitnesses have come forward to back up his story.

Abraham Thornton at the bar, from Cooper, J. (1818). A Report of the Proceedings Against Abraham Thornton… Warwick: Heathcote and Foden.

Thornton’s barrister asks a Birmingham man, who was milking cows on a farm on Thornton’s route home to Castle Bromwich, to confirm exactly when he saw the accused. The witness replies that it was ‘about half past four o’clock, as near as I could judge, having no watch.’

Q: How did you know what time it was?

A: My wife, who was with me, afterwards asked at Mr Holden, of Jane Heaton, the servant, what o’clock it was. She looked at the clock and told her.

Q: How long was it, after you saw the Prisoner, before your wife asked Jane Heaton what time it was?

A: Before she inquired, and after I saw the Prisoner, we had milked a cow a piece, in the yard, which might occupy us about ten minutes. The cows were not in the yard then, they were a field’s breadth from the house.

Q: And you think this time, in all, took up about ten minutes.

Clearly, estimating time from the number of cows you had milked is not an accurate way to tell the time and such testimony today would be almost worthless.

So how did people agree on exactly what the time was two hundred years ago? Before the Industrial Revolution, the position of the sun through the sky was enough to indicate sunrise, sunset and mid-day. If you lived within hearing of a church, the bells would signal services or key points in the day. The only people who really needed a more accurate idea of hourly time – the clergy, for instance – used measuring devices such as sand timers, burning candles or sundials (the latter only effective in sunshine of course). By the late 18th century, clocks and watches were proliferating, mostly amongst monied people, but even modest households might own a timepiece of one kind or another.

Essentially, however, people understood that there were three types of time: true time, calculated from a longitudinal position and the sun; conventional time, which might be signalled by a church clock or by a timepiece belonging to a trusted person; all the rest was estimated time.

Although there was no parish church in Erdington, meaning that witnesses in the Mary Ashford murder case had no way of knowing the conventional public time, some people did own clocks – but the accuracy of these depended on how the owner kept them. The victim’s best friend’s mother kept hers permanently about forty minutes fast in order to fool the household into getting up in plenty of time for work.

It was clear from the start that timings would play an important part in the case. One witness, a gentleman, told the court he habitually kept his pocket watch by ‘Birmingham time’, and that within hours of the discovery of Mary Ashford’s body had gone into the city to check that it was accurate.

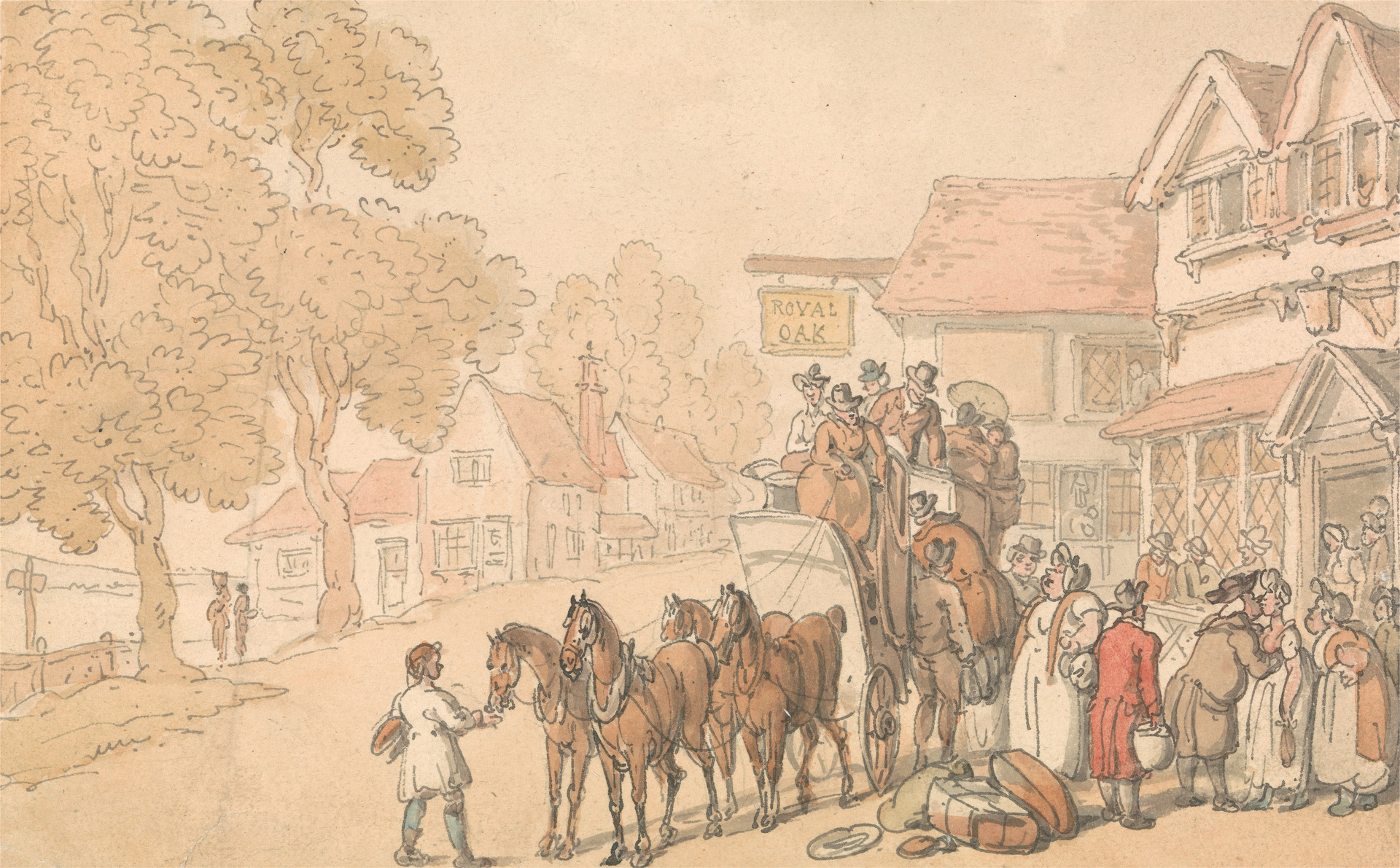

Thomas Rowlandson, Loading a Stage-Coach (The Royal Oak, Islington), undated. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

How did the transport system function if people across the country used different times? Stagecoaches advertised departure and arrival times and so needed a degree of standardisation. Guards carried timepieces that were adjusted to compensate for the local time differences arising from longitudinal position. They gained about 15 minutes in every 24 hours, when travelling west to east, and the reverse when coming back the other way.

‘A steam train on a line at a station with passengers travelling. Coloured aquatint by Havell after Calvert.’ Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

As the country became increasingly industrialised and workers found better wages in factories than on the land, keeping to specific and agreed times of arrival and departure became more important. ‘Clocking on’ became an accepted feature of working life.

However, it was the advent of the railways in the 1840s, along with the telegraph companies and the Post Office, that had the greatest impact on the standardisation of time. In 1840, the Great Western Railway was the first train company to order that London time be used in all its timetables and at all its stations. Over the next few years all the other companies followed suit but it took until 1880 for Greenwich Mean Time to be officially adopted as the standard throughout Great Britain.

The clock on the Corn Exchange has two minute hands: the black one shows ‘Bristol time’ while the red shows GMT. cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Rick Crowley

If the witnesses in the Mary Ashford murder case had kept accurate pocket watches all telling the same time, who knows, perhaps the outcome of the trial would have been different. As it was, after the trial, Thornton remained the prime suspect, and Mary’s family and their supporters were determined that he would not get away with his crime.