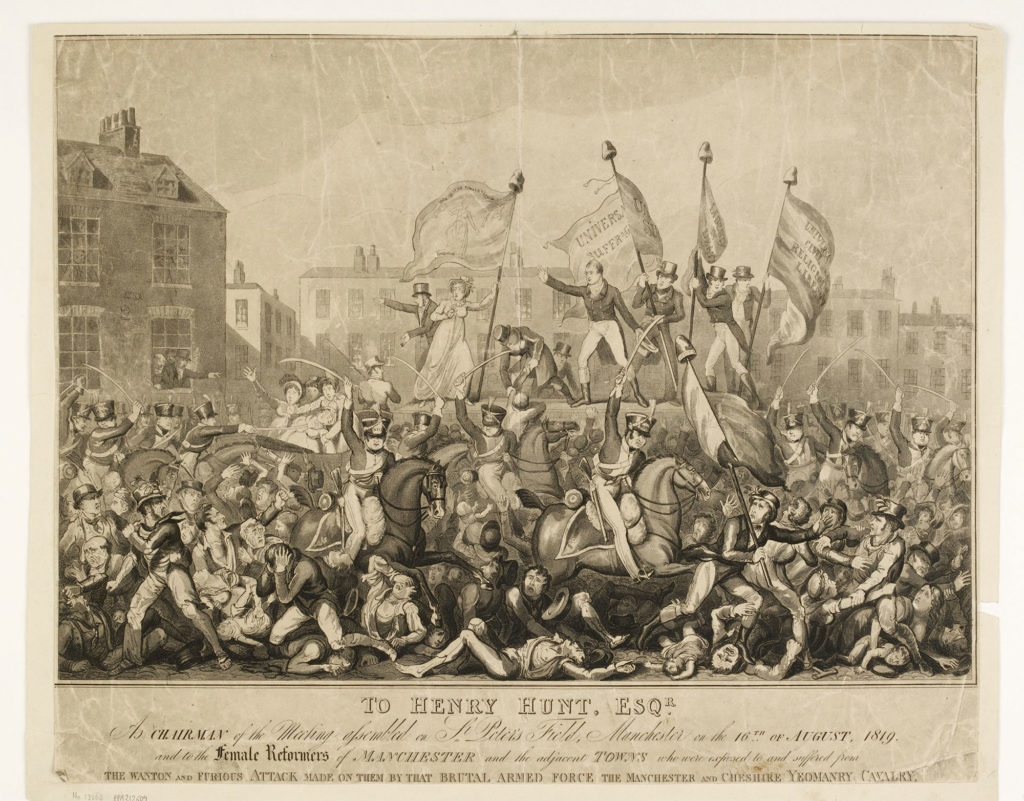

On 16 August, 60,000 men, women and children, most of them working people, from Manchester and surrounding towns and villages, assembled in St Peter’s Field, an urban square edged with buildings and fed by narrow streets. They were unarmed and dressed in their best clothes. Earlier, the men had practised marching, all the better to keep discipline. Some firebrands among them had wanted to bring arms — cudgels, pikes, knives — but were persuaded to leave them behind. The star speaker, Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt, threatened to pull out if the protestors had weapons.

They were understandably nervous, although there was something of a celebratory atmosphere. It was a lovely summer’s day, a Monday, and that was usually a working day. They had abandoned mills, factories and workshops to make their points: that Manchester was without parliamentary representation of any kind and that the franchise should be widened to all men. As the crowd strained to hear Hunt’s words, delivered from the hustings, a magistrate read the riot act. This meant that if the crowd failed to disperse they were liable to be charged with riot, a capital charge.1

No one in the crowd heard the magistrate’s words. He called in the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, drunk and itching for a fight, and after them the Hussars. The resulting bloodbath left an estimated 18 dead, their number including four women and a child, killed by sabre cuts and trampling. Hundreds were injured.

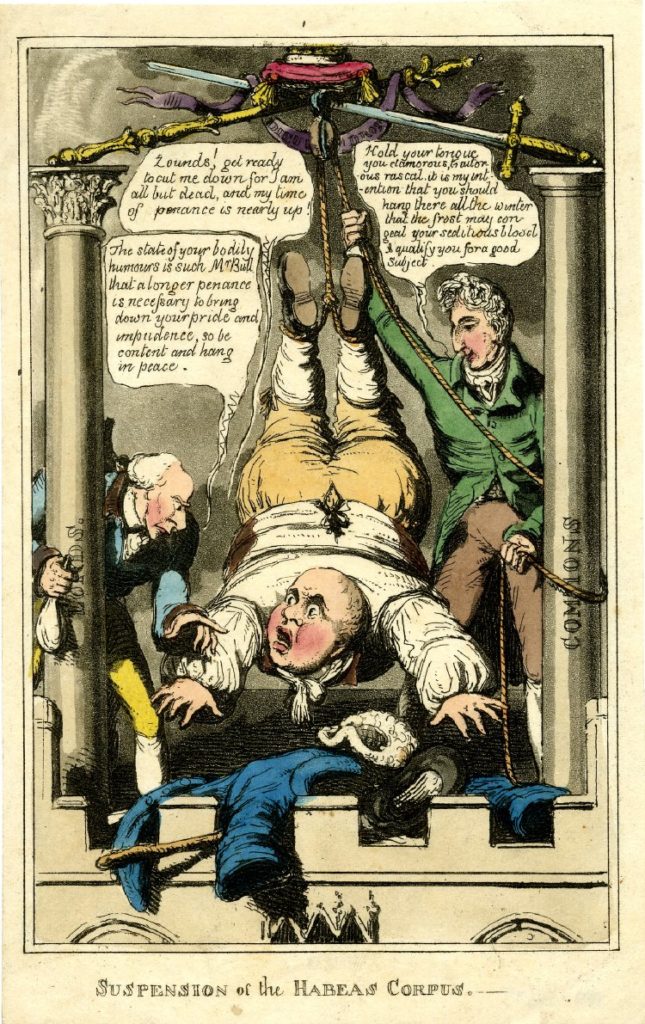

Mike Leigh’s film tells the story of that day by painting in the background: the aftermath of 20 years of war with France and the trauma of Waterloo; the Corn Laws that inflated the cost of bread, the staple diet of the poor; the inbuilt inequity of a political system that hands over £750,000 in thanks to the Duke of Wellington but begrudges ordinary people an extra shilling in their wages; the corruption of the ruling class, which happily exploits the poor and punishes them for objecting; their nervousness that calls for political rights would lead to a French-style revolution.

Leigh thinks Peterloo should be taught in school and I agree. Peterloo was a watershed, although it may not have felt so at the time. It joins other demonstrations of democratic aspiration, the Spa Field riots, the Blanketeers’ march and others, on the path to the Great Reform Act and ultimately universal suffrage.

I saw the film yesterday afternoon, in a chilly screen in Greenwich. Three hours is a long time to endure over-efficient air conditioning. Added to that, the projectionist had failed to turn off some of the overhead lights. Was Peterloo engaging enough to get me to ignore these distractions and immerse myself in 1819 Manchester?

Oh, how I wish I could say yes. There is so much to love in Peterloo. The locations are authentic. All that industrial red brick! those amazing weaving machines in perfect working order! the black interiors of the magistrates court! the rugged moors! the muted colours! The acting is great. The cast is brilliant but take a bow Maxine Peake, Rory Kinnear, Tom Gill. The clothes are realistic. There’s no we-just-got-this-back-from-the-dry-cleaners look I’m relieved to report. The music is superb. The role of women is not ignored. But…

But… There’s a lot of polemic. Speeches that are clearly taken from primary sources. Why would I object to that, I ask myself? It’s historical accuracy after all. But it sounds like preaching and it sits alongside the overdone explication (watch out for the potted rationale for the Corn Laws). I found myself thinking that I might prefer a straight-up documentary or a handout.

To my shame, I also found myself worrying about some of the details of the production. Would poor weavers really light candles – two candles, actually, and in the summer! think of the expense – so that they could chat to each other about politics at bedtime? Wouldn’t Joseph’s soldier’s jacket have fallen to pieces after four years of non-stop wear? Could magistrates really recommend to a higher court that unconvicted defendants be executed? Do we know that it was definitely a potato thrown at the Prince Regent’s carriage in 1817?

However… This is all pointless nit-picking. The problem with Peterloo was the script. Real events rarely fit neatly into a three-act story arc. Leigh tried to overcome this by bookending the film with the fate of Joseph, a bugler traumatised at the Battle of Waterloo, and unable to find work when he returned home (he was possibly based on real-life John Lees, who was sabred during the charge and who died of his wounds some days later). Joseph had given his soul to fight for his country, which callously cast him and thousands like him aside. But the film’s broad canvas means that individuals are painted in broad brushstrokes and poor Joseph never feels like a real person. It’s the same with the ‘baddies’, who are reduced to a bunch of pantomime villains.

Also, why did no one spot the spies lurking around the illicit Reformist meetings? They were wearing totally suspicious hats and gurned away like mad (cf Joseph Nadin, the wicked Deputy Constable of Manchester, and ‘Oliver the Spy’). At times, the film felt like melodrama.

Still, to tell the story of Peterloo in under three hours and to make its politics understandable to people who never have heard of it is a huge achievement. Ignore my petty peeves. It is an excellent, brave, ambitious film, flawed just as all excellent, brave, ambitious films are flawed. Go and see it on a big screen if you can. It is superbly photographed and beautifully produced, and it is very good at helping you understand what was going on in Britain 200 years ago. As it happens, there’s quite a lot of synergy with what is going on now… but that is an angle I’ll leave for another day.

- This was no idle threat. In 1812, Hannah Smith, one of the women in my book Women and the Gallows, was hanged at Lancaster Castle for riot and highway robbery alongside seven men found guilty of riot, arson, housebreaking and stealing food in the Manchester food riots.