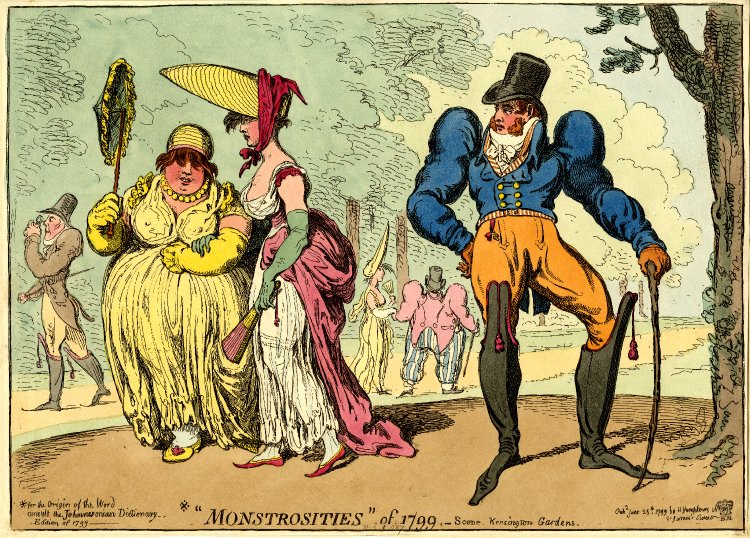

James Gillray, Monstrosities of Kensington Gardens, 1799. Published by Hannah Humphrey © The Trustees of the British Museum

In my previous post on James Gillray, I looked at “Monstrosities” of 1799 – Kensington Gardens, a copy of which was given to me for a recent birthday. One of my kind benefactors asked how people would have bought copies of such prints. Here I outline some of the aspects of the satirical print business, including information about Hannah Humphrey, who published Gillray for most of his life.

It is not a long journey from the satirical prints of Hogarth, Gillray, Rowlandson, Cruikshank to the cartoons of Steve Bell, Martin Rowson, Ben Jennings and others. But while the work of the latter is published in newspapers (and online of course), this distribution channel was not available in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Instead, prints were usually sold singly in dedicated print shops in the West End of London. There were also dealers in the area around St Paul’s in the City, but I will confine this post to those in the West End. Not all print shops dealt exclusively in engravings – books and maps were often also sold.

Among the most important dealers was Samuel William Fores, a Scotsman initially based in Piccadilly and from 1795 at the corner of 50 Piccadilly1 and Sackville Street, where windows on two sides of his premises allowed him plenty of space to advertise his wares. Although Fores sold the work of many artists, his most significant client was Isaac Cruikshank. Fun fact: For a while, Louis Philippe, duc d’Orléans, who went on to become King Louis Philippe I, lodged on the first floor, above Fores’ shop.

Attributed to Isaac & George Cruikshank, Folkstone Strawberries or more carraway comfits for Mary Ann, 1810, shows the front of S.W. Fores’ shop at the corner of Sackville Street and Piccadilly. Note that the majority of the items shown in the window are books rather than prints. Credit: The Print Shop Window

One of Fores’ direct rivals was William Holland, whose shop was located from 1782 at 66 Drury Lane and from 1788 at 50 Oxford Street. Gillray was initially among Holland’s artists until he was aligned exclusively with Hannah Humphrey. In 1793 Holland was imprisoned for selling a work by the radical Thomas Paine.

Richard Newton, William Holland’s Print shop c. 1794. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Unlike Fores and Holland, and later Rudolph Ackermann in the Strand, Hannah Humphrey (1745–1818) specialised in satirical prints – that is all she sold. She had inherited the business from her brother William when it was based in St Martin’s Lane and moved it first to Old Bond Street and subsequently to New Bond Street and then to 27 St James’s Street. Humphrey was that rare beast: the Georgian independent businesswoman.

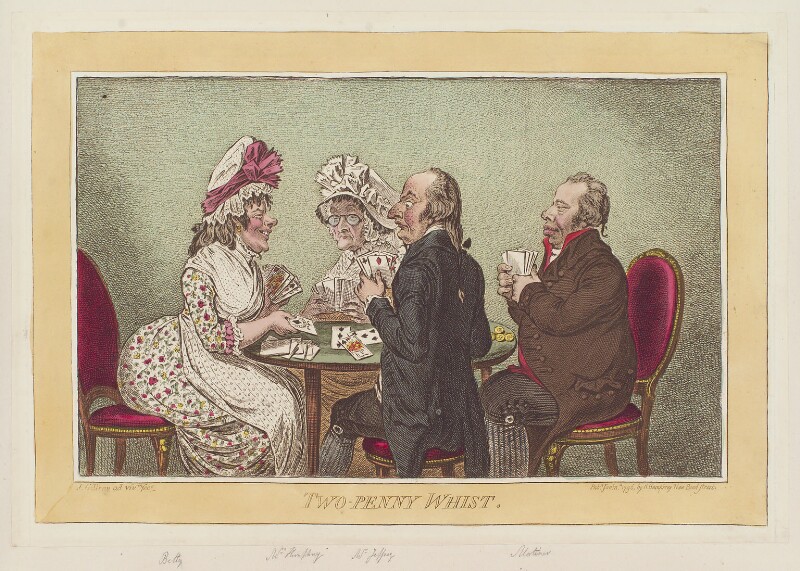

James Gillray, Two-penny whist (1796). Published by Hannah Humphrey, who is portrayed on the left. © National Portrait Gallery

Gillray lodged with Humphrey for twenty years and although some suspected an illicit relationship between these two single people it was in all probability platonic. They were clearly friends. When Gillray developed poor sight and descended into mental illness and alcoholism at the end of his career and was no longer able to work, Humphrey cared for him until his death.

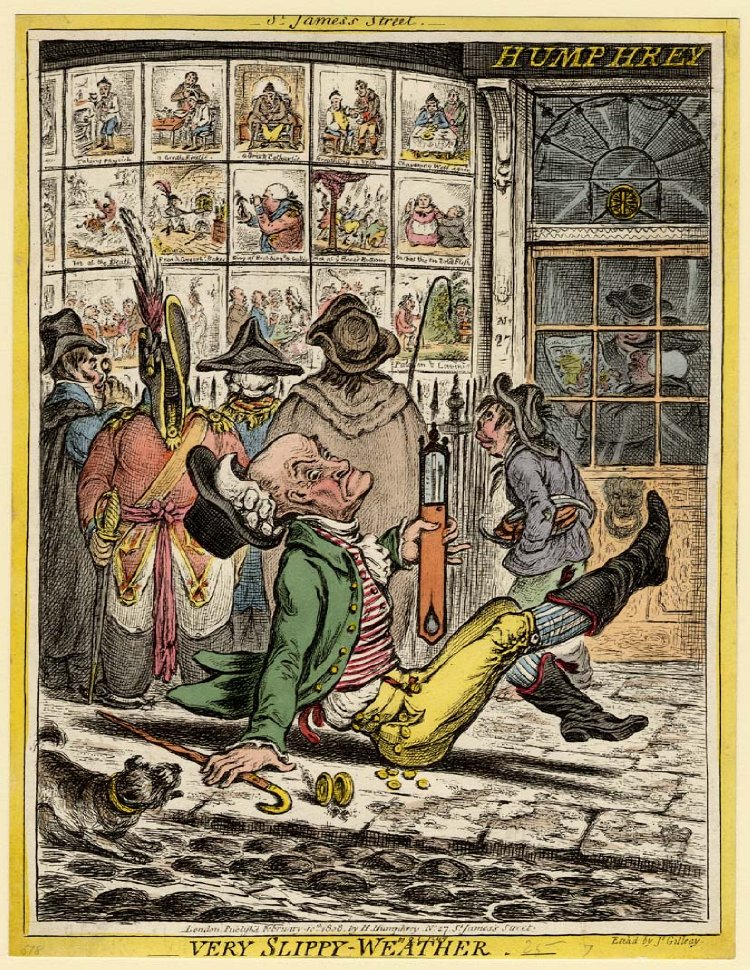

James Gillray, Very Slippy-Weather, showing Humphrey’s shop front in detail (1808) © The Trustees of the British Museum

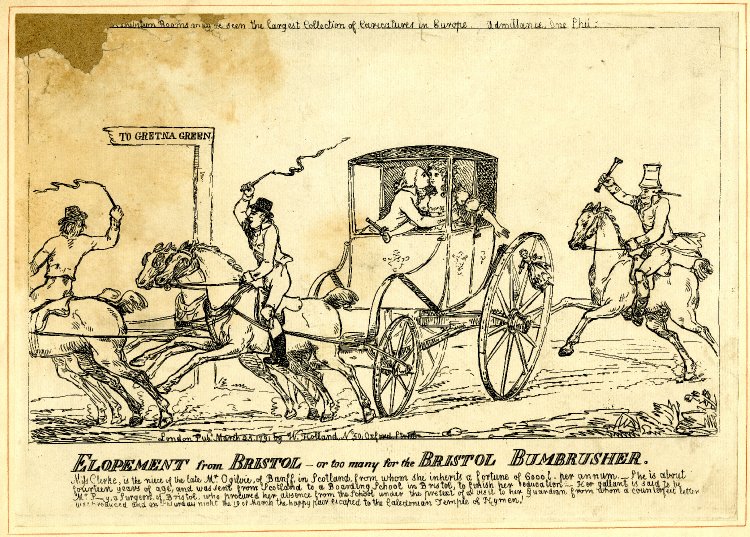

Although Gillray’s prints were pricey, neither he nor Humphrey made a fortune. There was simply not much money in the sector. To boost income print sellers occasionally put on exhibitions and charged the public for entrance. Sometimes a particular print would attract a crowd, which was good for business. This was the case with Elopement from Bristol– or too many for the Bristol bumbrusher and A Perry-lous situation; or, the doctor and his friends keeping the bumbrusher and her myrmidons at bay satirising the tragic case of the abduction and forced marriage of a 14-year-old heiress Clementina Clerke by Richard Vining Perry in 1791 and the frenzied efforts of Clerke’s former schoolteachers to bring Perry to justice for doing so.2

The popularity of Gillray’s work fell off as the 19th century progressed. Humphrey’s business was inherited by her nephew George, who sold it at auction in 1835.3

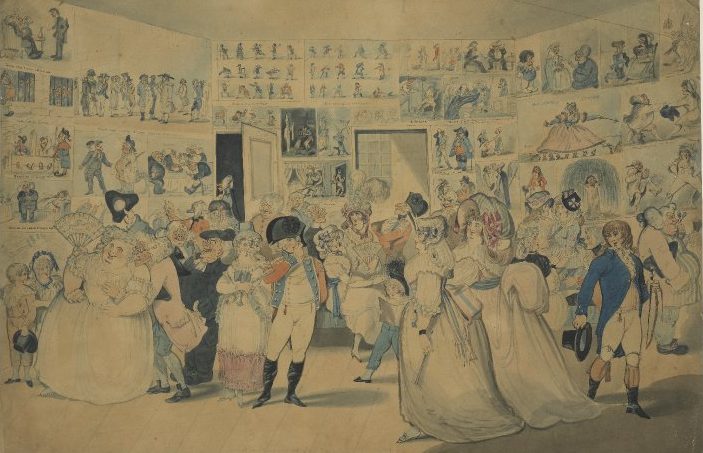

An 1821 caricature of Humphrey’s shop on St James’s Street. The figures seen through the door on the right are thought to include George Humphrey.

- Later renumbered as 41 Piccadilly.

- I wrote about this notorious case in 2013.

- Acknowledgement: The work of Mathew Crowther at The Print Shop Window, Heather Carroll at The Duchess of Devonshire’s Gossip Guide to the 18th Century and Robert L. Patten, Conventions of Georgian Caricature. Art Journal, Vol 43, Winter 1983, pp. 331-338 has been helpful in writing this post.