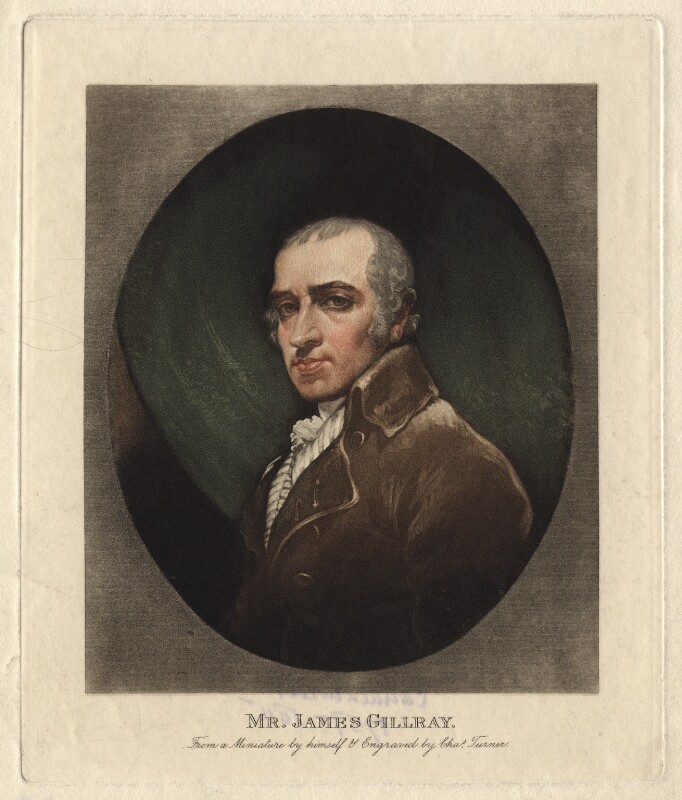

For a recent landmark birthday some kind and generous friends clubbed together to give me a hand-coloured print by James Gillray. As you can imagine, I was – and am – utterly thrilled with it. It set me off on a bit of a mission to find out more about Gillray and Hannah Humphrey, the woman who published it and who provided a home for Gillray for much of his adult life.

James Gillray’s satirical prints are among the most biting, bitchy and cruel of the cartoons produced in the long 18th century. No one, whether humble or high-born, escaped his scorn. His work has been described as ‘corrosive acid poured relentlessly on mankind’.1

Born in 1756 or 1757 in Chelsea, where his Scottish soldier father was a pensioner, Gillray first trained as a letter engraver but was soon bored and went off with a band of strolling performers instead. On his return to London he enrolled at the Royal Academy, where he started to produce etched caricatures heavily influenced by Hogarth under several pseudonyms.

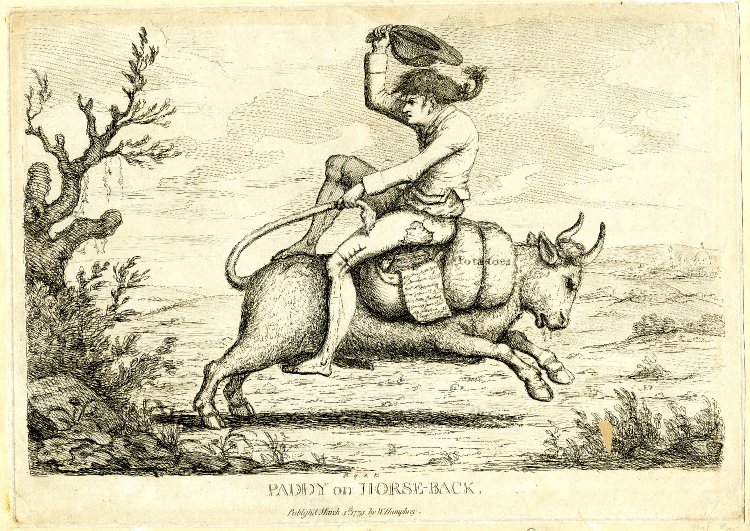

Gillray’s first attributable etching, produced when he was in his early twenties, was Paddy on Horse-back (1779), which shows an uncouth Irishman seated backwards on a bull galloping across open country towards London (St. Paul’s is visible on the right) where he hopes to make his fortune. The print was published by William Humphrey, whose sister Hannah later inherited his business and continued to publish Gillray (more about her in Part 2).

Despite receiving a government pension, Gillray’s soul was not for sale – he targeted politicians of all stripes and, of course, the Royals, who provided plenty of inspiration. Although George III did not really ‘get’ the humour, his eldest son, the Prince of Wales, did and was sometimes deeply upset by it. He was known to have acquired in 1804, secretly, through a chosen third party, the copper plate of L’Assemblée Nationale purely in order to destroy it and halt further circulation. The portraits were, it appears, too near the knuckle.

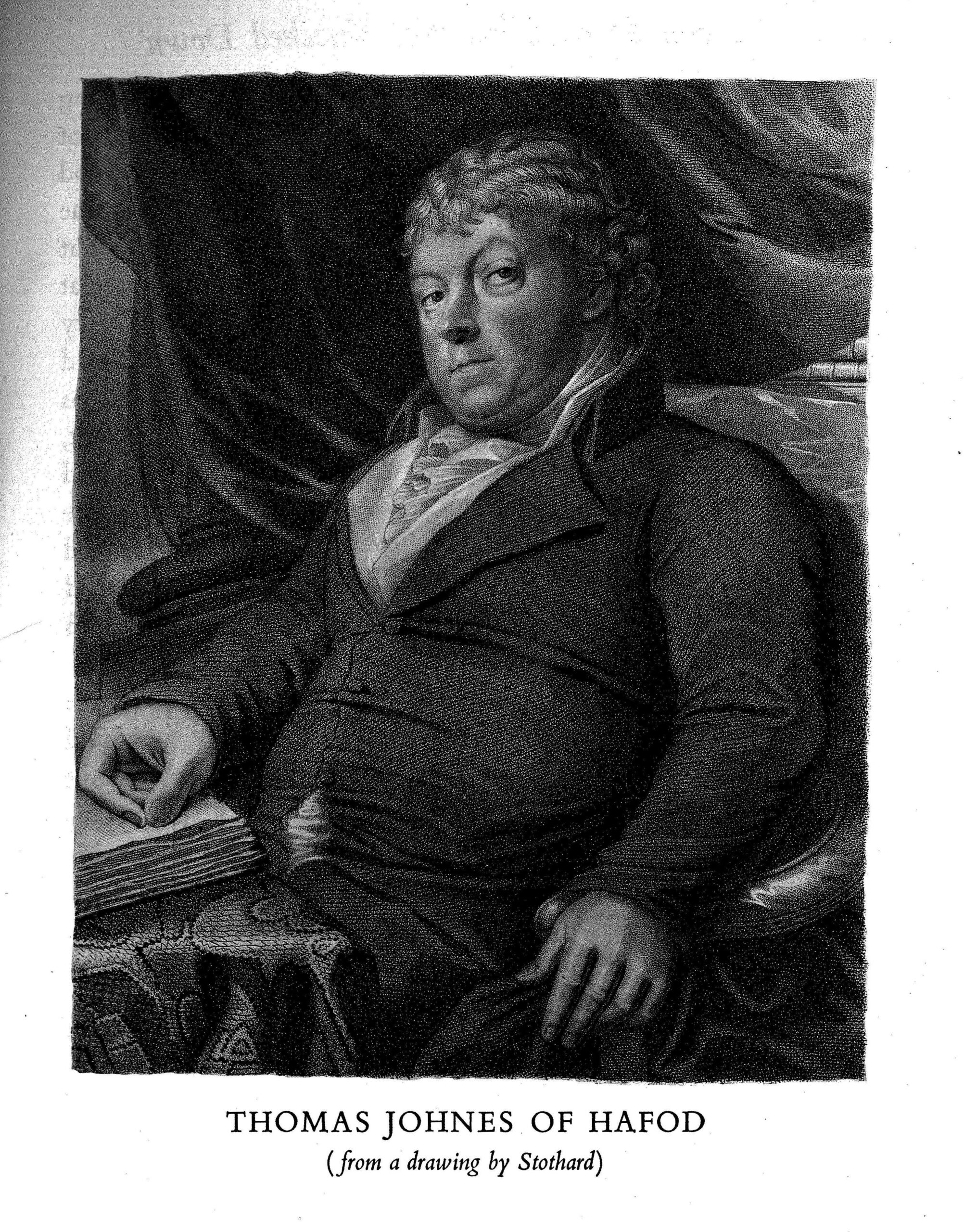

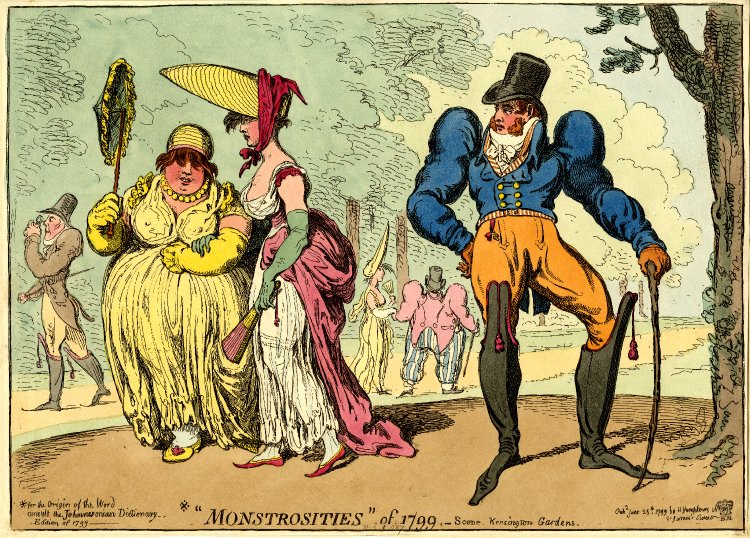

The print I was given is “Monstrosities” of 1799, shown below, a satire on the extremes of fashion. The print is all about titillation and cheap allure. The impressive gentleman on the right is thought by some sources to be Thomas Johnes (1748–1816), a gentleman farmer and M.P., of Hafod in Cardiganshire – which presents us with a problem.

Johnes was cultured and kind and, if his commissioned portrait is anything to go by, not particularly vain or style-conscious. He was notable for his attempts to upgrade the estate he inherited and to transform the lives of his poverty-stricken tenants. There is nothing about the dandyish figure in Monstrosities, who sports ridiculous over-the-knee tasselled boots, fullsome sideburns, soaring shoulder pads and a boldly sexually declaratory expression, that screams Welsh farmer.

However, there is a passing facial resemblance between him and Johnes, although Johnes would have been over 50 when the print was published. Perhaps Gillray was being ironic and the print was an in-joke whose meaning is now obscure.

2Further evidence of Johnes is in the note in the bottom left corner, asking us to consult the ‘Johnnesonian [sic] Dictionary Edition of 1799’. One possibility is that it is not Thomas Johnes who is referenced but some other member of the family. If anyone can solve the mystery, please get in touch.

The women’s attire is just as extreme as the men’s. The taller of the two in the foreground wears an over-sized ‘poke’ bonnet and her gauzy, translucent gown is, like her companion’s, obscenely revealing. She sports a cork rump (for more on these read All Things Georgian’s wonderful post False Rumps!) and they both have hair cut short in back with a long frizzed fringe.

Seven years after this print was published, Gillray’s eyesight began to fail and his output dropped. Depressed, he turned to drink. In 1811 he suffered a bout of severe mental illness and attempted suicide. Mrs Humphrey took care of him until he died in 1815, aged only 58. He was interred in St James’s churchyard in Piccadilly. His work was hugely influential. In 1818, Cruikshank produced the first of a series of satirical prints titled Monstrosities. His take on absurd contemporary fashions harked back to Gillray’s.

- Frédéric Ogée, James Gillray, London. The Burlington Magazine, Vol 143, No 1183 (Oct. 2001), pp. 644–645.

- R. J. Moore-Colyer described Johnes as ‘an exceptionally cultured squire’ in his 1992 A Land of Pure Delight: Selections from the Letters of Thomas Johnes of Hafod, Cardiganshire, 1748-1816. Lladysul: Gomer Press.